Paleobiology is full of enigmatic fossils. Another such example is a small bone from the Triassic period, discovered 184 years ago in Scotland and examined many times. New analyses have shown that it is not a turtle bone, but a bone of a cynodont, an ancestor of mammals.

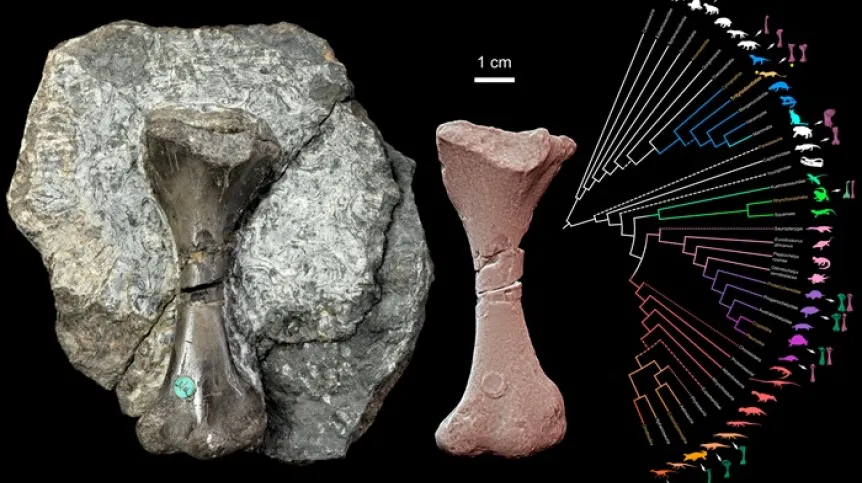

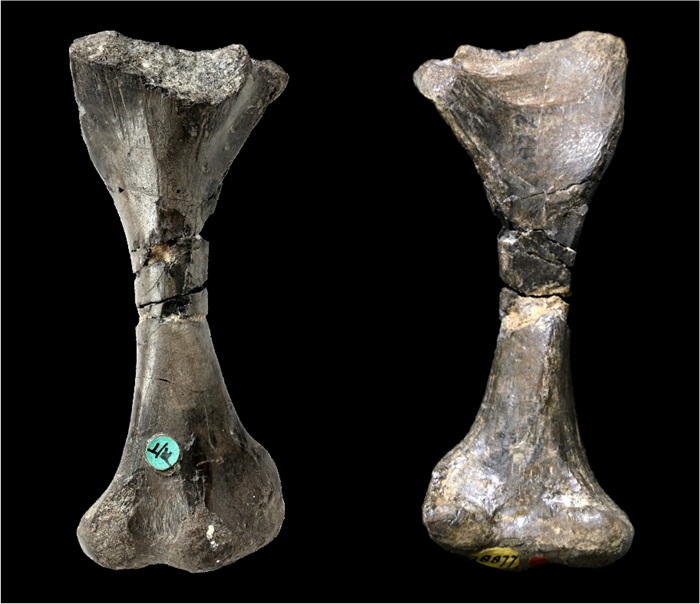

'Saurodesmus robertsoni bone has been a mystery for nearly two centuries. The specimen, found in the early 1840s, is a damaged femur, which was repeatedly examined by the most eminent palaeontologists of their time. Over the decades, it has been attributed to turtles, archosaurs, primitive reptiles (Parareptilia), and synapsids (representatives of the evolutionary line that includes mammals). We have described it again and we believe that it does not belong to a representative of reptiles - as previously believed - but to a cynodont (probably a tritylodontid)', says Dr. Tomasz Szczygielski from the Institute of Paleobiology of the Polish Academy of Sciences, the first author of the publication on this subject in the journal PLOS.

Cynodonts are a group of animals from which mammals are derived and to which they belong. They resembled a small rodent the size of a rat that lived a rather hidden life, possibly in underground burrows.

The slightly damaged bone is less than 10 cm long and over 200 million years old.

According to Tomasz Szczygielski, the specimen was found before Darwin announced his theory of the evolution of organisms by natural selection (1859). He adds that although assumptions about the evolution of species had already begun to appear in the community, discovered fossils were still usually being matched to modern animals. This was also the case with Saurodesmus robertsoni, which was initially believed (and this hypothesis lasted the longest) to be the femur of a turtle similar to today's softshell turtles. Another hypothesis suggested that the specimen might belong to a crocodile. However, not all the pieces fit into this puzzle, which is why researchers have tried to solve this puzzle many times over the decades - so far to no avail.

Tomasz Szczygielski specializes in the study of vertebrates, especially turtles from the Late Triassic period (230-210 million years ago). That was how he came across Saurodesmus robertsoni - a specimen historically identified as a fossil of a Triassic turtle.

To solve the mystery and finally verify whether the bone belongs to a turtle or not, the researcher and his colleagues decided to prepare an overview of the anatomy of the epiphyseal limb bones of amniotes (reptiles, amphibians and mammals).

'We analysed the epiphyseal bones of the limbs, i.e. femurs and humers in various quadrupeds. First, we looked for reptiles - based on previous classification attempts. After some time, however, our hypotheses began to move towards cynodonts. Then it turned out that the bone had a unique combination of features and belonged to an advanced cynodont, most likely a tritylodontid, one of the closest representatives of this group to early mammals', the scientist says.

Moreover, it turned out to be the oldest known representative of cynodonts from Scotland.

According to the scientist, returning to historical collections, re-examining them and comparing them with the current state of knowledge pays off.

'A review of old specimens and their verification is very necessary, because I think that there are a lot of such misinterpreted specimens. Most often, it was not due to the bad will of the authors, but rather to the state of knowledge at that time, incomplete skeletons or difficult access to original comparative materials and the need to work only with two-dimensional photos, and sometimes even only sketches. Today, we can use archives from all over the world (mostly available online), and we can also create 3D models of specimens that are almost perfect reflections', Szczygielski says.

'In addition, we conducted a cross-sectional review of the anatomy of the epiphyseal bones of the limbs in various animals. This information was previously scattered in the literature, and we have collected it in one place, which may be of use to other researchers in the future', says Szczygielski.

PAP - Science in Poland, Agnieszka Kliks-Pudlik

akp/ zan/ kap/

tr. RL