'Inter-species gene exchange' and using genetic solutions developed by other species is a standard among animals, research by scientists from the Jagiellonian University shows.

This view challenges the traditional emphasis on maintaining genetic 'purity' in the protection of endangered species.

Biology classes teach that when animals of different species interbreed, they cannot produce fertile offspring. A prime example is the mule - a hybrid between a donkey and a horse, which is usually infertile.

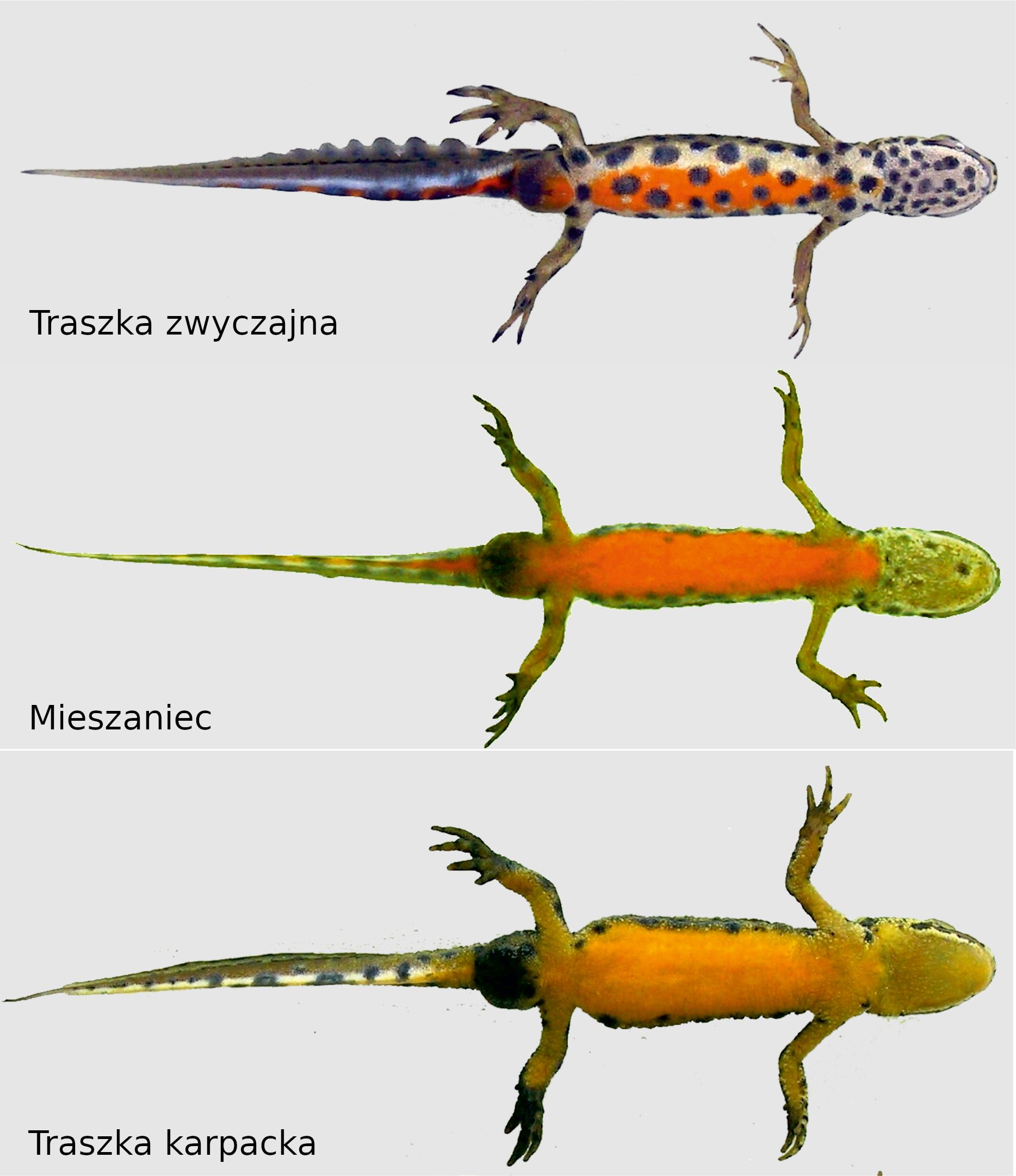

Life is not so black and white, however: it escapes from the pigeonholes invented by humans. In nature, the boundaries between species blur quite often, and closely related species frequently interbreed. This process is called hybridisation.

Offspring resulting from interspecies breeding often function much worse than their parents - for example, they have a high mortality rate before they reach reproductive age. This is due to excessive differences in the genome of the mother and father and the existence of many incompatibilities between the two species. It is difficult to combine such divergent features in one organism.

However, it sometimes happens that the offspring are capable of reproduction. And they pass on their genes.

The creation of less successful hybrids does not have to be an evolutionary dead end. It brings long-term benefits to the entire species, because it enables the flow of pathogen resistance genes between species.

Scientists from the Jagiellonian University analyse this mechanism in a paper in Molecular Biology and Evolution.

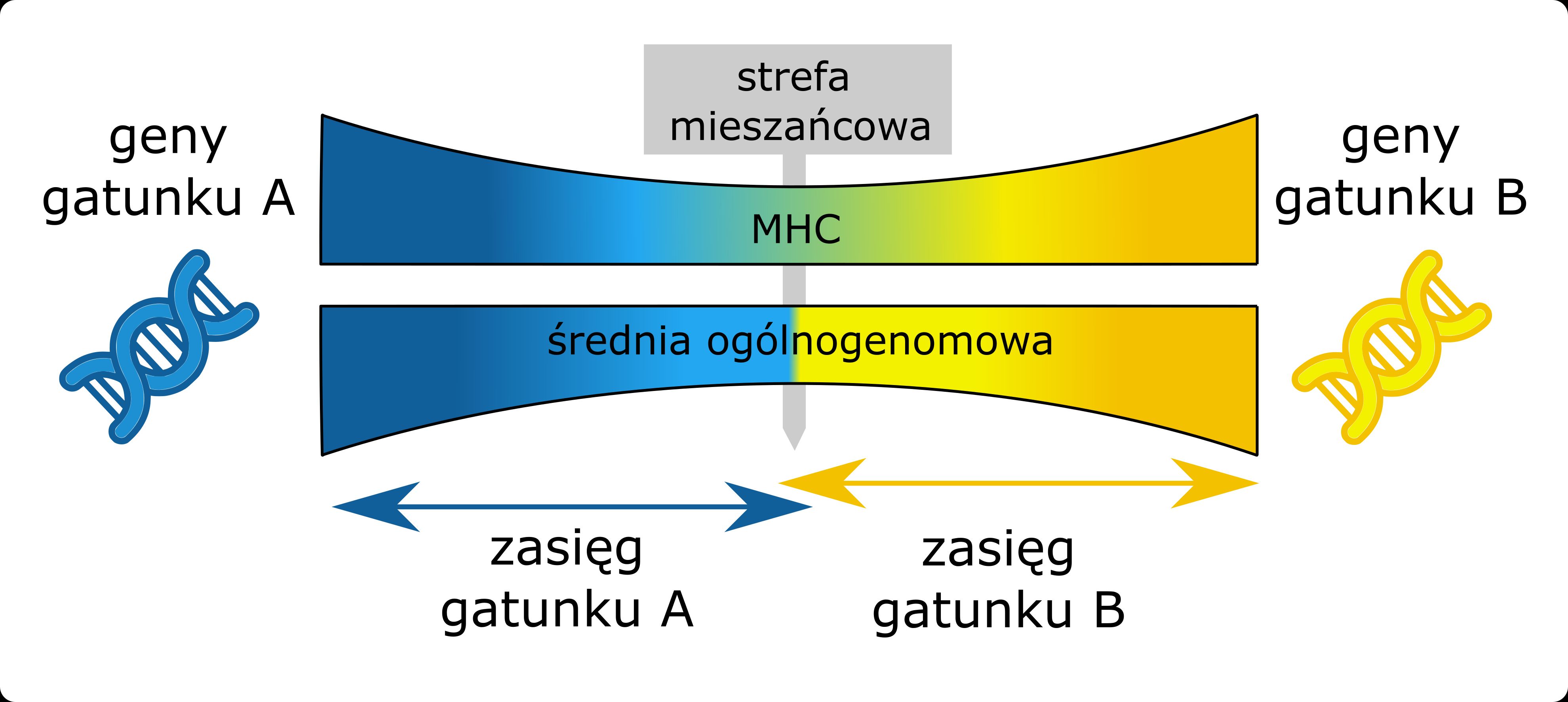

Research by Dr. Tomasz Gaczorek and the team from the Jagiellonian University show that interspecies gene transfer - the technical term is introgression - is usually very limited. However, some types of genes, such as those related to immunity, can overcome the inter-species barrier more easily than others.

Among the potential candidates for genes providing a direct benefit to one of the species, the Major Histocompatibility Complex (MHC) genes are often mentioned.

The immune system has an important task: defend the body and fight anything that threatens it. Therefore, it must efficiently distinguish foreign cells, such as parasites or pathogens, from the body's own cells. This is the task of the Major Histocompatibility Complex. Parasites and pathogens do everything they can to avoid detection and live peacefully at the expense of the host. Therefore, if the host develops an improvement in its defence against intruders - a new 'detector' of foreign cells - difficult times are coming for the parasites. Fresh variants of MHC genes in the gene pool of a species are therefore extremely desirable.

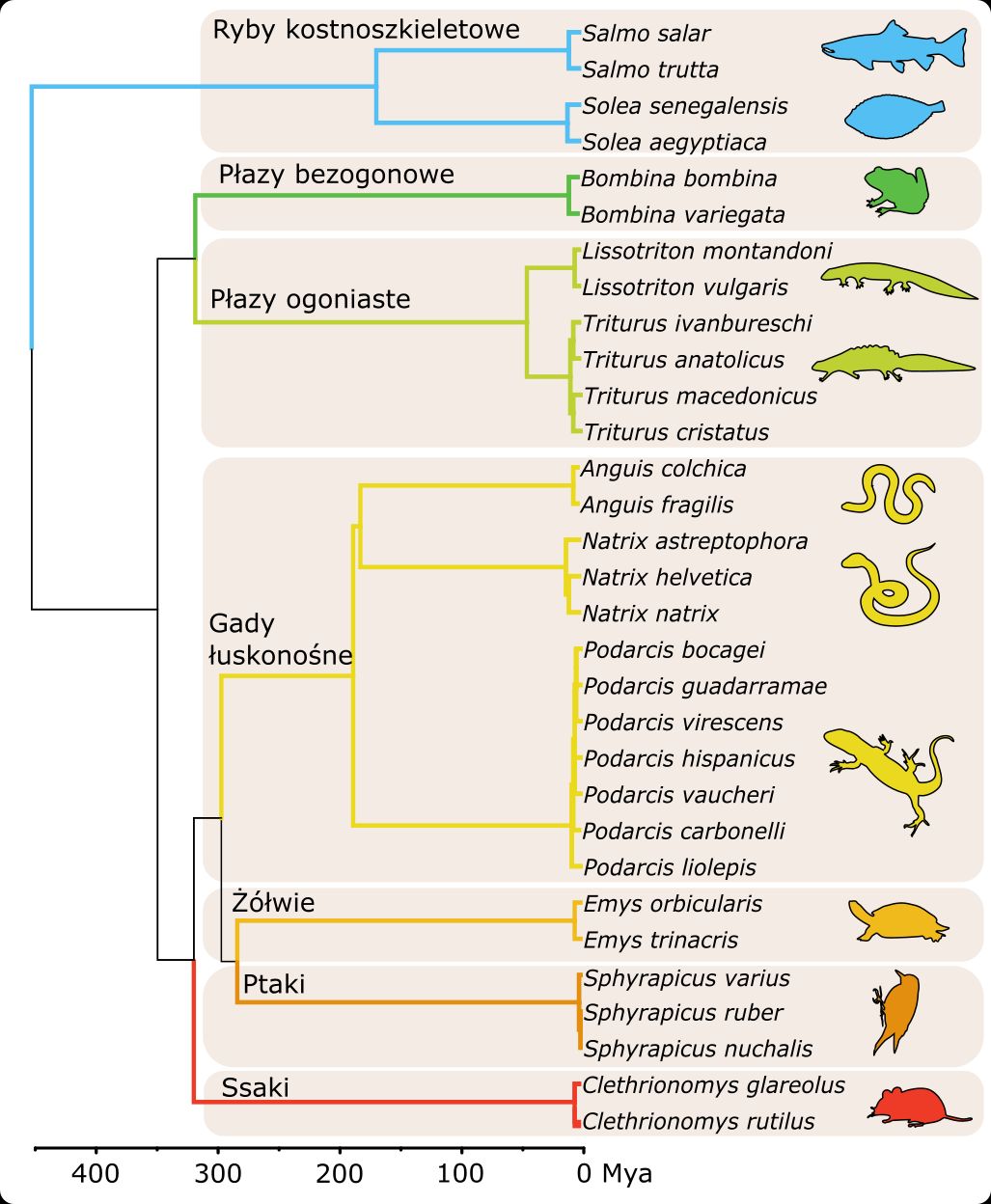

The international team of scientists led by Professor Wiesław Babik from the Jagiellonian University compared the rate at which MHC and other genes introgress in different hybrids. Almost 30 different groups of hybrids were analysed, including fish, amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals.

The study clearly demonstrated the commonness of MHC gene introgression between species and provided evidence for a much faster rate of MHC gene introgression compared to the genome-wide average. This means that while most genes of a different species are quickly eliminated from the genome of subsequent generations as incompatible, new MHC genes in a given species are accepted 'with open arms' and passed on to offspring. The study also showed that this is a continuous and ongoing process, probably allowing species to respond more quickly to emerging threats.

'These findings have important implications for practical conservation', the scientists write. The common view so far has been that in the protection of endangered species, the purity of the genetic pool should be maintained at all costs and endangered animal species should not be crossed with related species. This study shows, however, that such an approach may hinder effective adaptation in the face of new pathogens.

.'The presented research is therefore consistent with the postulate raised for some time in the scientific community, of active protection of species by increasing their genetic variability, which may be crucial for their survival during the observed climate changes', the team write in a press release.

PAP - Science in Poland, Ludwika Tomala

lt/ zan/ kap/

tr. RL