Wolves are very social animals that have a huge impact on the functioning of the entire ecosystem. That is why it is so important to protect them and get to know their true face, not the one based on stereotypes and myths, argues Sabina Pierużek-Nowak, PhD, a professor at the University of Warsaw.

Sabina Pierużek-Nowak, PhD, a biologist and professor at the University of Warsaw, has been conducting research on wolves for 30 years, covering ecology, behaviour, the dynamics of recolonisation of new areas, and the genetic structure of the population. She is also the President of the Association for Nature WOLF. The scientist is also involved in activities for the protection of large predatory mammals and promotes knowledge about these animals.

Science in Poland: Let me start by asking how you perceive the recent Council of Europe decision to change the status of the wolf from 'strictly protected' to 'protected'? (The status of the wolf is regulated by the Bern Convention. The change requested by the European Commission is a gateway to changing the regulations in the European Union. The Ministry of Climate and Environment announced in early December that Poland did not intend to lower the protection status of the wolf.)

Dr hab. Sabina Pierużek-Nowak, prof. UW: I view this decision with great concern, because I know that the consequence will be a change, or at least an attempt to change the status of the wolf also in the EU Habitats Directive. And that will open the way to legal hunting of these predators in the member states of the European Union.

SiP: One of the arguments for this change was that the wolf population in Europe has recovered and no longer requires such strict protection. How large is the wolf population in Poland?

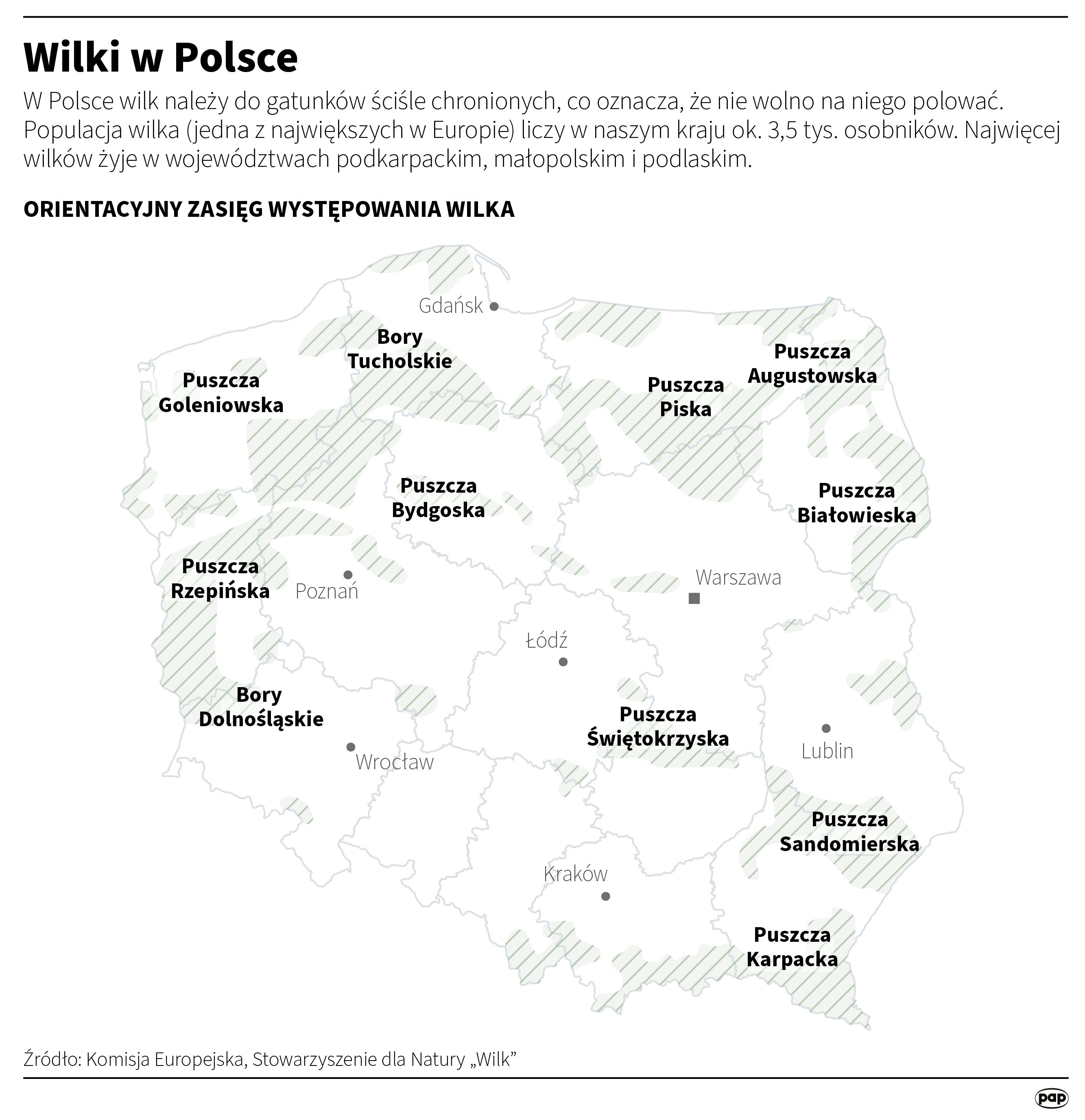

S.P.-N.: We now estimate it at approx. 3.5 thousand individuals. We use various methods to estimate the number of wolves wilków because, due to the huge expenditure it requires, there is no annual national monitoring of the population of these predators in Poland. Therefore, we base these estimates on field data collected by us and our collaborators on the current range of the population, places where dead wolves have been found, but also on information provided by people interested in observing nature, who, for example, install camera traps in forests and record wolves. In this way, we join forces within the framework of citizen science.

SiP: Is 3.5 thousand individuals a lot or a few?

S.P.-N.: On a European scale, this is quite a lot, because the total wolf population in 35 European countries (excluding Russia and Belarus) was recently estimated at approx. 23 thousand individuals. However, our population is special, because it is a source of wolves for neighbouring countries, especially Germany, Czechia, Slovakia and Ukraine. Unfortunately, our wolves' migrations to the east and north have been blocked by the recently built border walls with Belarus and Kaliningrad (totalling 380 km), and soon, for the same reason, communication with Ukraine will also be lost. Thanks to the strict protection of this species introduced in Poland in 1998, i.e. before we joined the European Union, wolves spontaneously recolonised forests in the western and central parts of the country, where they had previously been exterminated, as well as countries in Western Europe. The aim of protecting this species was to increase its numbers and protect its positive impact on large populations of wild ungulates.

SiP: And why should we protect wolves and care for their population? What is their role in the ecosystem?

S.P.-N.: Wolves have an important ecological role, which means that this species affects the healthy functioning of the entire ecosystem. First of all, they reduce the densities of wild ungulates such as red deer, roe deer and wild boar. Wolves, through predation on large herbivores, protect the forest - especially young trees and undergrowth plants - from being gnawed, and enable its regeneration. In addition, these predators, due to their limited body structure, hunt the slowest to escape, and therefore the weakest individuals, thus positively affecting the age and sex structure of the roe deer and red deer populations and their health condition.

SiP: Wolves are perceived to be aggressive animals. People are afraid of them. Should they be?

S.P.-N.: The way we perceive animals depends on our experiences with them. And since - statistically - we have probably never had contact with wolves, we rely on oral, written and film accounts, with these accounts having a very significant influence in childhood. And these legends and fairy tales for children perpetuate the view that the wolf is a murderous, dangerous and aggressive animal - also for people. It is undoubtedly a predator that kills large animals, but it is not the type of villain from frightening stories.

Hence the huge role of scientists and educators to pass on their experiences to others and combat harmful stereotypes. I have been conducting research on wolves for 30 years and I have been educating for just as long. We try to bust myths based with the latest scientific knowledge, but unfortunately, not everyone believes us. In addition, the media often repeat the bad image of the wolf in their messages, fuelling the sense of threat. Currently, with the population growing and people increasingly coming into contact with wolves, we must talk about this species as honestly as possible, not only to prevent unnecessary panic, but also illegal, harmful actions against these predators.

SiP: Could you give an example of such behaviour, deviating from the stereotypical thinking about wolves?

S.P.-N.: For example, it is a common belief that wolves are excellent killers. This is not the case at all. Scientific research in the USA, as well as our own observations, e.g. thanks to camera traps, show that their hunts are often ineffective. Besides, the so-called wolf pack is not a gang of vicious, cruel killers. It is simply a family group of individuals of different ages, fitness levels, skills and personalities.

SiP: What are the members of such a group?

S.P.-N.: A parental pair, which manages the group's activity due to their parental duties, and its offspring. These are over-a-year-olds that are still under the care of their parents, but will soon leave the family, and this year's puppies. Usually, there are about 8-10 individuals, of which only two to four hunt, and the rest wait for food to be delivered. Wolves live up to 10 years in natural conditions.

I admit that I am fascinated by the functioning of such a family group of wolves, because many of its members' behaviours are similar to our, human ones. For example, the parents' great dedication to raising the youngest offspring, which extremely cements the family. The appearance of puppies turns the male into a very caring and determined father, whose most important task is to provide food for the offspring and his partner during the first period of nursing the puppies, when she cannot leave the young. Then, when the older offspring takes over care of the young, the parental pair hunts and brings them food together. Family ties within such a group are extremely strong and lasting.

SiP: What is the range of wolf occurrence in Poland?

S.P.-N.: It occurs basically throughout the country, in all forest complexes. Currently, wolves like to live at the interface of forest and field areas - in the forest it is easier to find a safe shelter, e.g. for puppies, while in the fields it is easier to hunt, e.g. for the numerous roe deer and wild boars, and even red deer, which during the growing season, until late autumn, feed in large-scale corn, rapeseed and other crops. It is in these fields that wolves are seen by people. The largest number of wolves live in western Poland. Interestingly, the wolf population in these areas at the end of the 20th century was so small that it had practically no chance of survival, and today it is there that it is growing the most, which is facilitated by the large forest cover and large population of wild ungulates. After protection was granted, wolves from north-eastern Poland were the source population from which settlers in the west of the country and in Germany came. From there, they wandered throughout the lowland part of the country - and since a wolf can walk even several dozen kilometres in one day, they reached areas several hundred or even several thousand kilometres away in Western Europe.

SiP: So the Bieszczady Mountains are not the main wolf refuge in Poland?

S.P.-N.: In the past, when wolves were a game species, their main national refuge was in the Bieszczady Mountains. However, the Polish Carpathians have their limitations resulting from their smaller area than the lowlands (they occupy only 6.3% of Poland's area) and the enormous pressure of tourism, even in the Bieszczady Mountains. In addition, our mountain forests are intensively exploited. Wolf family groups are territorial, they need a lot of space to live - one family occupies a territory of 250 to 400 square kilometres. This means that there are less than 500 wolves living in the entire Polish Carpathians.

SiP: At what rate and to what size can the wolf population in Poland develop, for example in the next decade?

S.P.-N.: It is difficult to assess. Firstly, as I have already mentioned, wolf groups have huge spatial requirements, so the number of groups in a given complex is very limited by its area. The abundance of the food base, i.e. the number of wild ungulates, is also very important. In addition, the high mortality of wolves also has an impact - including deaths caused by humans, although not always intentionally. I mean road accidents, in which several dozen wolves die each year. In autumn, we receive up to two calls a day about a dead wolf on the road. Most of them are puppies, but there are also parental individuals - their deaths cause not only the death of the puppies dependent on them, but also the disintegration of the entire group.

In addition, unfortunately, illegal shooting of wolves and trapping are a big problem. Our very conservative estimates indicate that over 140 wolves are killed by firearms each year. Wolves also sometimes fall into traps that poachers use to catch wild ungulates.

Wolves also struggle with various diseases, including dangerous tick-borne diseases caused by parasites transmitted by ticks, including invasive species that are increasingly settling in our climate due to global warming. Not to mention the consequences of environmental pollution – for example, crops growing in soil contaminated with pesticides are eaten by wild ungulates, which are then killed and eaten by wolves. This is particularly dangerous for wolves, because as apex predators, they accumulate various types of chemical pollutants in their tissues.

SiP: You mentioned that the bonds in a wolf group are very strong. Can a wolf form a bond with a human?

S.P.-N.: An adult or a few month old wolf is unable to form any kind of bond with a human. Even if, for example, you save it from a car accident, this individual is terrified and convinced that treatment and rehabilitation are not help, but abuse. Therefore, after being released, it will avoid people even more.

The situation is different with small puppies, and it is especially problematic when they come to people as 2-3 week old babies. All wild wolves, growing up for over a year in family groups, learn most of their behaviours, hunting methods and survival in the environment from their parents and siblings. Therefore, if such a baby is separated from the wolf family and then kept and fed by people, and even worse, showered with affection like a dog, in later life it will perceive people as its brethren. Then - even after being released into the forest - it will avoid wolves and seek contact and food from people. Such wolves, even after reaching full adulthood, will not be able to live fully in the natural environment and will be a source of huge conflicts with local communities, which will inevitably mean a death sentence for them. Therefore, for the good of wolves and people, we must not allow such situations to happen and refrain from any form of assistance to wolf puppies encountered in the forest. Even seemingly innocent feeding of puppies in the forest ends in their dependence on humans for food and, as a consequence, in lifelong captivity.

SiP: And what should we do if we encounter a wolf in the forest? How should we behave?

S.P.-N.: I would be happy [laughs]. I say this because I have encountered wolves many times and I know that they will not do me any harm, they will just go away after a while. However, if someone feels uncomfortable, they may start waving their hands or shouting. Our scent and voice will scare the wolf and the animal will leave.

SiP: You combine your scientific work with running the Association for Nature WOLF. What does the Association do?

S.P.-N.: The Association has been operating for almost 30 years. It was established when wolves were not protected in the whole of Poland, and one of our priorities was legal changes to ensure this protection.

Today, the scope of our activities is broad. We conduct activities for their protection and maintaining the connectivity of wolf habitats, we carry out many research projects on this species using the latest methods, such as GPS/GSM telemetry. We educate and promote the latest knowledge about these predators, and ways to prevent conflicts with human economy, especially damage to livestock, and we rescue wolves from oppression resulting from human activity, treat and rehabilitate injured and sick predators and reintroduce them to the environment.

SiP: How big is the group of Polish scientists who study wolves?

S.P.-N.: Research on wolves requires much more commitment than research on other animal species, and you will not get far without passion. This is long-term and extremely demanding research, with the need for constant readiness to respond to emergency situations, e.g. to answer phone calls about observed live or found dead wolves at any time of day or night, to make emergency field trips and interventions, often on weekends, to engage in patient conversations with panicked people, angry livestock farmers and hostile hunters. In addition, the species itself, which leads a nocturnal lifestyle, is difficult to observe and requires the use of advanced, modern research techniques and large financial resources. We currently have three dynamically operating centres researching wolves in Poland: the Mammal Research Institute of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Białowieża, the Faculty of Biology of the University of Warsaw, where I work, and a developing centre at the Faculty of Biology of the University of Gdańsk.

SiP: To sum up our conversation, what fascinates you most about wolves?

S.P.-N.: Their extraordinary intelligence, ability to learn, remember and pass on knowledge accumulated in life to other wolves in the family group. The aforementioned huge bond between individuals in the group, the constant need to communicate and their protectiveness. It turns out, for example, that wolves not only howl at each other (which everyone knows), but in direct contact they communicate with each other quietly by squeaking, which sounds very affectionately; they, even very adult individuals, also genuinely like fooling around and petting. Healthy wolves take care of and share food with sick and disabled family members, which often allows them to survive. The bond between the parent pair is also incredible; apart from the period of nursing puppies, the pair is practically inseparable.

Besides, the longer I study wolves, the more evidence I see that matriarchy prevails in their family groups. It is the female that accepts the partner, chooses the place and digs a burrow for the puppies that are about to be born. When she is not taking care of the little ones, she is the one who initiates hunting trips (she is a great tracker and hunter) or fights with neighbouring groups or intruders when she feels her family is threatened. As you can see, wolves display many behaviours similar to humans [laughs] - and this is really fascinating. (PAP)

Science in Poland, interview by Agnieszka Kliks-Pudlik

akp/ bar/