The coevolutionary interactions between avian brood parasites and their hosts can lead to selection for refined defences in the host to avoid parasitism and increased specialisation of the parasite to specific hosts. A new study by researchers from the Museum and Institute of Zoology, PAS, show how these interactions can lead to diversification in the phenotypes of hosts and parasites and contribute to the formation of new species.

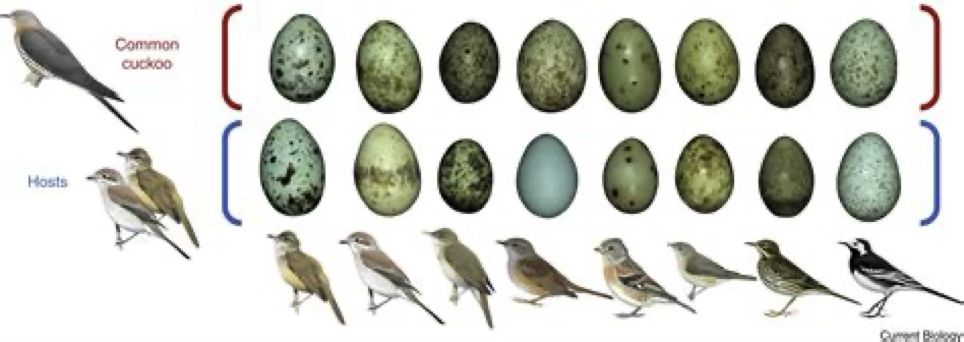

The interactions between avian brood parasites and their hosts are textbook examples of evolution in action and have fascinated biologists for over a century. Avian brood parasites lay eggs in the nest of other birds, their hosts, which are left to incubate the parasite eggs and raise the parasite nestling. Many hosts of brood parasites in Europe, Africa, Americas and Asia recognise the egg of the parasite and remove it from their nests.

However, these hosts do not distinguish the parasite nestling from their own and always accept the demanding brood parasitic chick feeding it until it is ready to leave the nest. As a consequence, brood parasites in these regions have evolved eggs that closely resemble those of their hosts as a strategy to escape host recognition. However, the nestlings of these brood parasites looks very different from the nestlings of their hosts because they do not risk being rejected by their host parents.

Things are very different for the brood parasitic shining bronze-cuckoo (Chalcites lucidus), which parasitises several hosts species in Australia, New Caledonia and New Zealand. Its hosts do not remove the parasite eggs from the nest, therefore the cuckoo eggs look very different from the host eggs. However, some hosts can recognise and reject the cuckoo nestlings, which has resulted in the cuckoo nestlings matching the appearance of the host nestlings in each region. This close resemblance in nestling appearance increases the chances that the cuckoo nestlings will escape recognition by the host parents and survive until fledging.

The visual resemblance between parasite and host nestlings is remarkable, with the cuckoo nestlings mimicking the colour of the skin, the colour of the bill and the structure of the feathers, or lack thereof, of their main host. This makes very difficult for the host to recognise the cuckoo nestling, paving the way for the successive line of defence, which is to recognise the cuckoo nestlings via their begging calls.

Researchers from MiIZ PAN, in collaboration with colleagues from Australia and New Zealand, analysed the begging calls of shining bronze-cuckoo and host nestlings of different ages from Australia, New Caledonia and New Zealand. The results show that the cuckoo nestlings from each region produce begging calls matching more closely those of their local host than any of the cuckoos from the other regions. The most accurate the begging call mimicry, the less likely is for the host to recognise the cuckoo and reject it from the nest.The strong selection pressure to avoid host discrimination promotes accurate visual and acoustic resemblance of the host by the cuckoo nestlings. This causes cuckoo nestlings to appear and sound different from each other even though they belong to the same species.

The shining bronze-cuckoos from Australia, New Caledonia and New Zealand are geographically separated from each other during the breeding season. Additionally, they are also genetically isolated year-round because they use different migratory routes and wintering grounds. Geographic isolation and specialisation on a local host are thus key factors in promoting the remarkable variation in the appearance of the shining bronze-cuckoo nestlings. This has led to the formation of cuckoo subspecies that over time could potentially diverge into separate species.

The study shows how brood parasitism can contribute to the astounding variation of animal morphology and behaviour found in nature. This adds a novel chapter to the study of brood parasite-host interactions by revealing new and surprising aspects of these intriguing biological systems.

kap/