Some birds adapt their sounds to the environment, others only sing in noise, Michał Budka, PhD, an eco-acoustician from the Adam Mickiewicz University says in an interview with PAP. He adds that birds compete for singing space just like they do for food or territory.

Michał Budka from the Faculty of Biology of the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań has devoted the last three years to the issues of eco-acoustics. This field of science deals with all sounds in the environment, including those made by living beings (biophony) and the sounds of natural elements - such as splashing water or rustling trees (geophony). Anthropogenic noise, such as cars, can also be heard in cities.

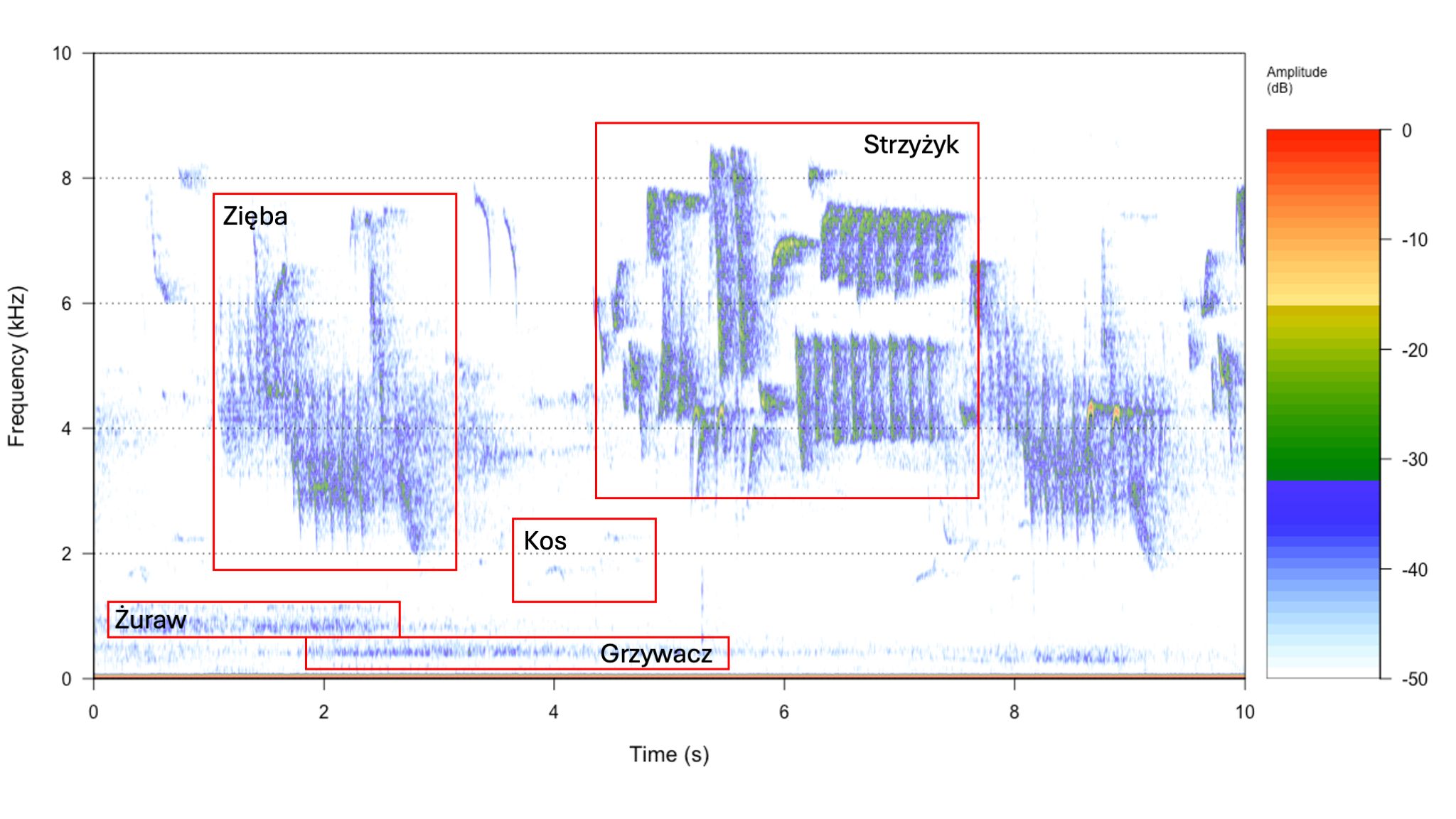

The expert explains that animals compete for many resources, including food, partners, and breeding sites. They also compete for acoustic space, i.e. the time and frequency in which they vocalize, which birds especially need for communication. From the point of view of communication efficiency, it is important when birds sing (this concerns both the season and the time of day), what frequency (pitch) their voices produce and what the amplitude (loudness) of these sounds is.

Budka, head of the project 'Interspecies competition for acoustic space in birds', says that birds use several strategies. 'In open areas, they usually sing at higher frequencies and faster, their songs have short components. In forests, bird vocalizations are usually longer, slower and at lower frequencies. So if we have two species that sing in the same frequency range, they should do so in different places, at different times of the day or at different times of the season', he describes.

The ecoacoustician has chosen Sweden, Poland and Uganda as the locations for his experiments because the biodiversity and numbers of animals increase from the poles to the tropics, which means that animals function in completely different acoustic environments.

'I also wanted to take into account the different lengths of day and night, and the length of the breeding season in different latitudes. In Sweden, the breeding season usually lasts several weeks and then there is practically no night, so birds can sing around the clock. In Poland, a temperate zone, the breeding season lasts two to three months, during which all breeding species sing; and during this time the length of day and night changes. In the tropics, on the other hand, the length of day and night does not change, the breeding season lasts all year round, there is seasonality related to rainfall, but other animals also vocalize, including insects, amphibians and mammals', he explains.

His team conducted the first research in the Białowieża Forest. 'At over 80 locations, we checked what species we hear every minute. It turns out that at the beginning of the breeding season, the species singing similarly are distributed in different places, which means they avoid each other in space. However, species arriving later disrupt this pattern', the ecoacoustician says.

'There is a hypothesis that songbird species exchange over time - but it only works before dawn, at least in temperate forests. After sunrise, similar species often drown each other out', he says.

In the rainforests of Uganda, in Kibale National Park, birds compete for acoustic space with each other, but also with monkeys, cicadas and frogs. Scientists checked the reaction of the green-backed camaroptera (Camaroptera brachyura) and the scaly-breasted illadopsis (Illadopsis albipectus) to new sounds appearing in the environment.

'The illadopsis stopped singing when we played vocalizations of another species with a similar song, and sang when there was silence or the noise had a different frequency than its own song. It chose conditions in which it could be heard well. On the other hand, the camaroptera sang more intensely in noise than in silence', Budka says. Similar behaviours were previously described in Australian zebra finches (Taeniopygia guttata) and canaries (Serinus canaria).

'Studies of vocal activity of birds in noise-polluted environments have shown another interesting phenomenon. It turns out that in cities or near airports, birds sing much earlier at dawn, when the intensity of car or air traffic is still low, or the frequencies of their songs are much higher compared to environments not polluted by noise', the researcher describes.

Experiments with the thrush nightingale (Luscinia luscinia) conducted in Poland have shown that, depending on the noise frequency, males select those components of their song of their repertoire that minimize the masking of their song by noise: they can lower and raise the song frequency.

The experimental part of the project has ended. The team from the Adam Mickiewicz University recorded tens of thousands of hours of research material. Now the scientists use artificial intelligence to search the materials for individual species and calculate the degree of complexity of the entire acoustic space - i.e. the presence of sounds made by different birds.

Papers by Michał Budka and colleagues on the subject of competition for acoustic space have been published in Animal Behaviour and Behavioral Ecology.

PAP - Science in Poland, Anna Bugajska (PAP)

abu/ agt/ bar/ lm/