A devil's rock - a boulder that a giant carried across the frozen Baltic Sea, a stone left during the Swedish Deluge... Ethnologist Robert Piotrowski, PhD, analyses the stories of erratic boulders from northern Poland - both the scientific ones and those immortalized in legends.

Large boulders scattered here and there in the lowlands are characteristic of the young-glacial landscape in northern Poland. Today, we know that these are erratic boulders (erratics) - large pieces of rock that were carried to Poland and left behind by the glacier that reached here many thousands of years ago.

A geologist or petrologist can tell exactly where a given stone came from, and thanks to radioisotope studies, also determine how long it has been on the surface of the earth and how old various damages on its own surface are. For centuries, however, the inhabitants of the areas near the boulders had no idea about glaciation. And they tried to explain the presence of such large stones in their vicinity with the help of fantastic stories.

'Erratic boulders are therefore not only just geological heritage, but also our cultural heritage', says Robert Piotrowski, PhD, from the Interdisciplinary Research Team on the Anthropocene at the Institute of Geography and Spatial Organization (IGiZP) PAS. During field research in Pomerania, he often asked people living in the area where the erratic boulders were located. In most cases, no one knew that. But when he asked the same people about the so-called devil's rocks - the location was given immediately.

'A rock is identified by a story and in this way becomes part of the cultural landscape. This is because such a narrative works better on the imagination and allows for better memory of information than a dry explanation from an encyclopaedia', the researcher points out.

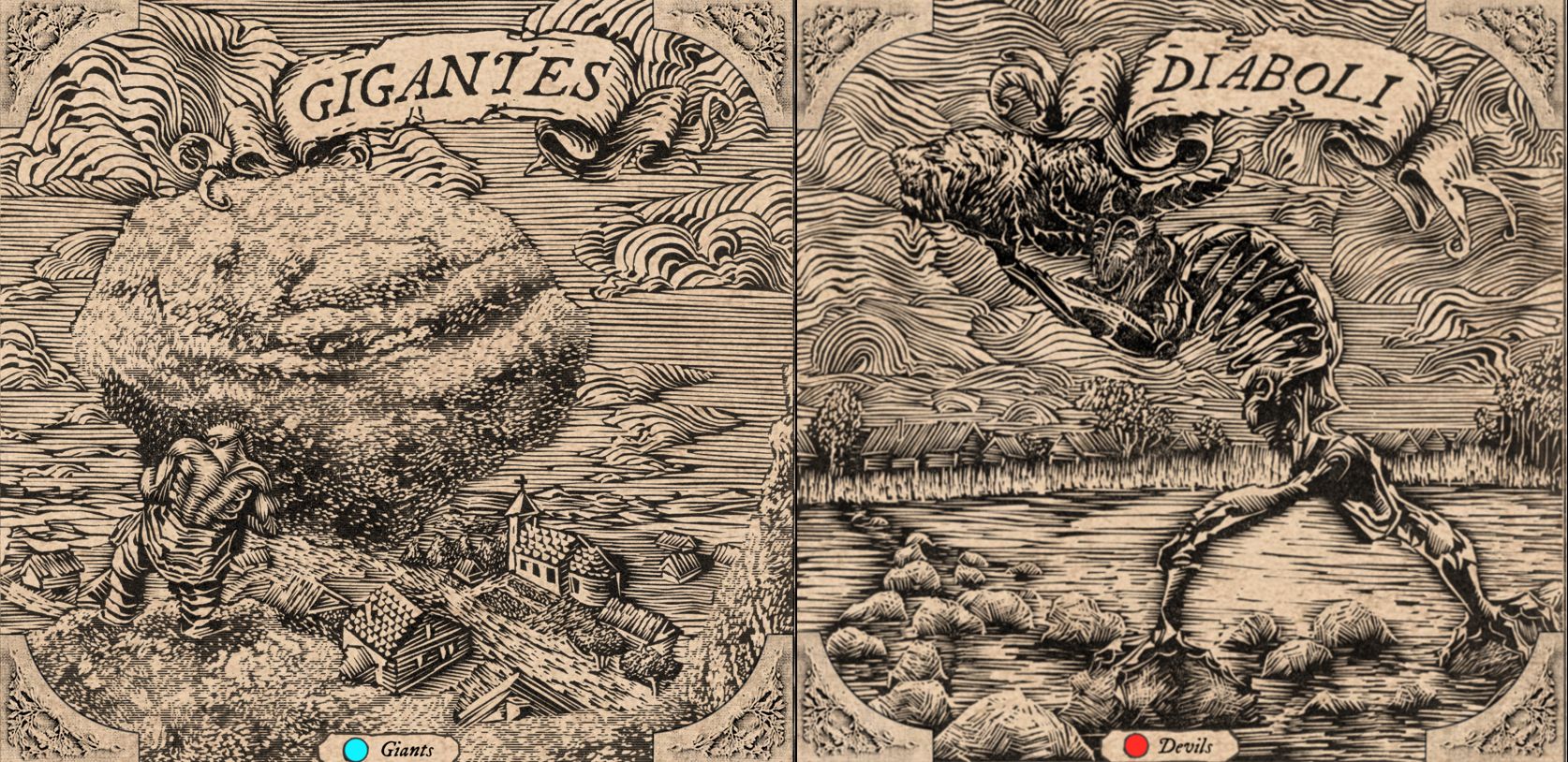

In the oldest legends about the origin of boulders, giants throwing stones appear (which is indirectly connected to Indo-European ideas about giants supporting the stone vault of heaven; erratic boulders could have been fragments of the sky).

'I found legends connected to a specific boulder, in which it is said that it was brought from Sweden - from across the sea - by a giant. And in another legend, there is a story that a giant carried the boulder across the frozen Baltic Sea. It is extraordinary how the folk narrative coincides with the scientific narrative', the ethnologist explains.

In later narratives - for example from 100 or 200 years ago - the devil began to appear in the legends, who, for example, tried to destroy the church in the village with it. And in even younger versions - the moving of erratic boulders was associated with the Teutonic Order or the Swedes invading Poland. There are also stories about someone being turned into a stone; that it was a stone on which witches danced, or that stones grew from under the ground.

According to the researcher, erratic boulders were an excellent material for the production of millstones and the construction of megalithic tombs. However, the belief in their supernatural origin would often save them from destruction.

'Folk legends influenced the first forms of unconscious protection of inanimate natural monuments', the ethnologist adds.

Piotrowski describes the history of the boulder on Rombinus Hill in Lithuania. It was said that in the 19th century, a local miller wanted to use it to make millstones, but no one from the area wanted to help him, because the boulder was considered untouchable. Workers from further away were brought in, because they were not afraid of the curse, but several unfortunate events occurred during the breaking of the boulder and its transport, which were interpreted as the result of breaking the prohibitions concerning the sacred stone. 'One worker broke his leg, another lost an eye, and, while the stone was being transported, the third was crushed by pieces of the boulder. The miller, in turn, became a drunkard and lost his fortune. Everyone claimed that this was punishment for destroying the sacred boulder', Piotrowski says.

'We can show a devil's rock with its interesting legend to tourists or residents, explaining that it has enormous significance for both geologists and the local community, and it is a part of their cultural identity. For example, we can create tourist trails and interest children in the incredible nature of the stone, to tell them about the geological history of the area. The combination of these two aspects results in a stunning - geocultural - mix', he points out.

Scientists are conducting research as part of the Polish National Science Centre project 'Heritage of ice giants. From geomythology to cultural geomorphology of erratics in the young-glacial area in Poland'.

PAP - Science in Poland, Ludwika Tomala (PAP)

lt/ zan/ jpn/