Palaeontologists from the University of Warsaw and the Polish Geological Institute – National Research Institute have described the first known Jurassic-era representative of the pycnodont fish group from Poland — a distant evolutionary relative of today’s parrotfish. The fossil dates back approximately 148 million years to the age of dinosaurs.

“This is the first such find from Poland and more broadly – Central and Eastern Europe, because so far only specimens from Western Europe have been known,” said Dr. Daniel Tyborowski, lead author of the study and researcher at the Faculty of Geology, University of Warsaw. “We can therefore supplement our knowledge about the evolution of pycnodonts from the age of dinosaurs in our part of Europe, which until now has been basically a blank spot.”

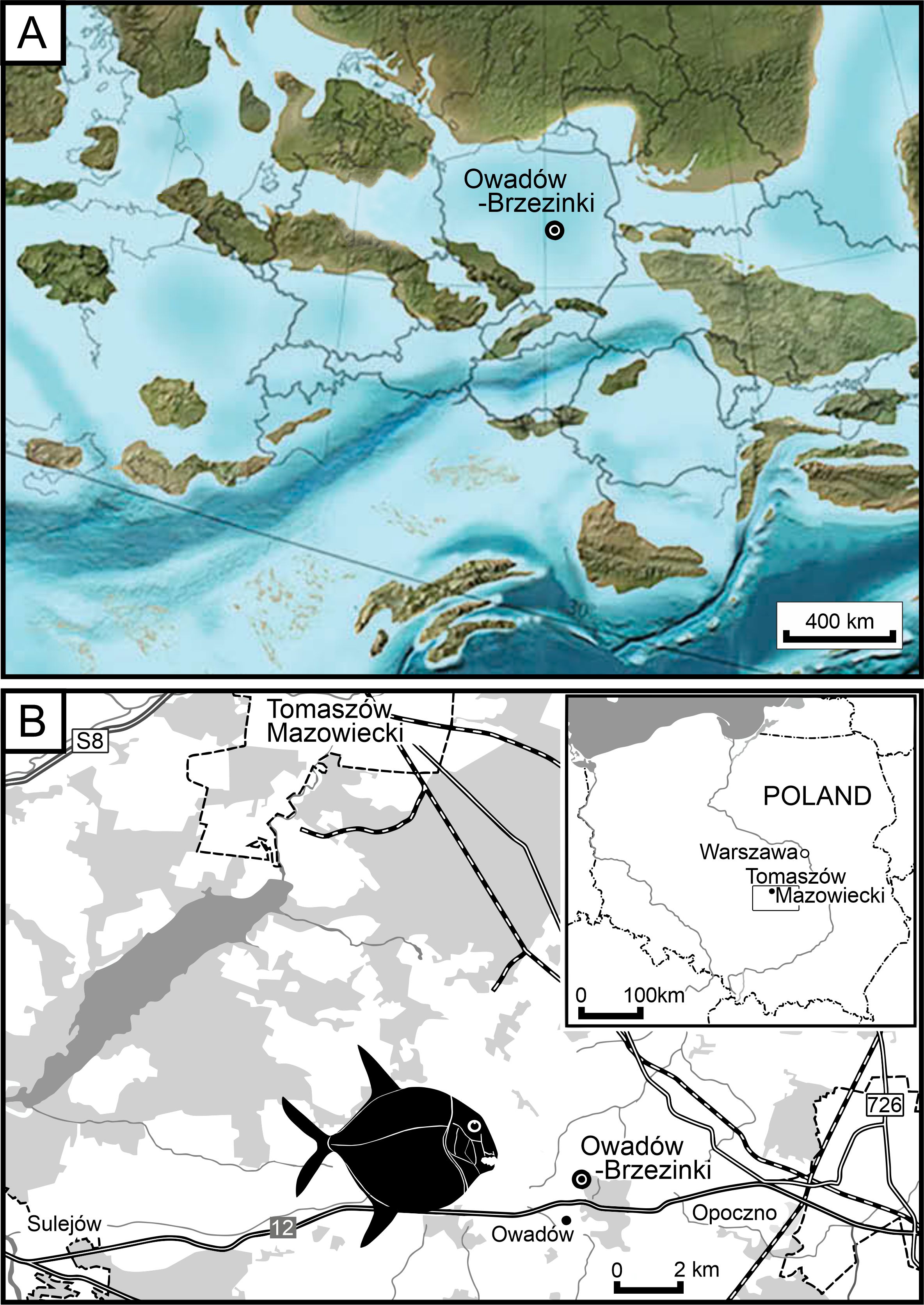

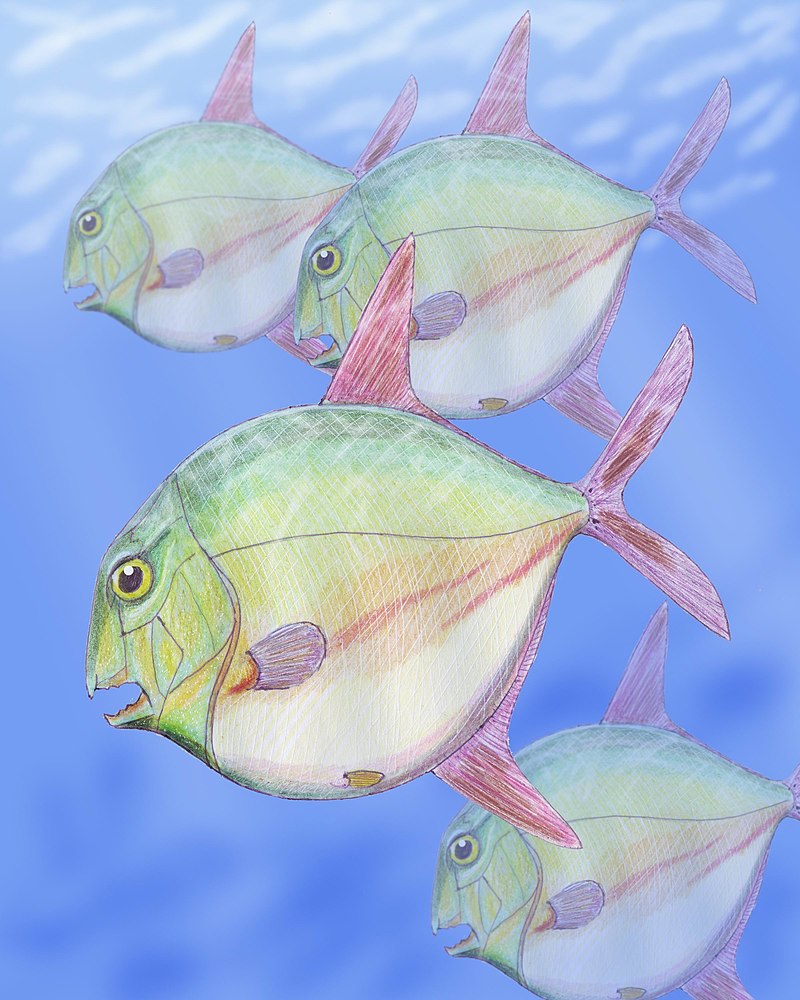

The find, a well-preserved toothed upper jaw of a pycnodont fish, was uncovered several years ago during fieldwork at the Owadów-Brzezinki quarry on the northwestern edge of the Świętokrzyskie Mountains. Researchers believe the fossil belonged to a small, circular-bodied reef fish, around 20 to 30 centimeters in diameter.

“At the end of the Jurassic, this area was an archipelago of tropical islands in the middle of a shallow sea,” Tyborowski said. “Lagoons formed between the islets, where life was vibrant, including a rich, developing ichthyofauna.”

The fossil belongs to the Pycnodontiformes, an extinct order of ray-finned fishes that first appeared in the Triassic period around 240 million years ago and went extinct about 35 million years ago at the end of the Eocene. The reef-dwelling fish reached peak biodiversity during the late Jurassic, playing a crucial role in marine lagoon ecosystems.

“We know from other, more complete finds that the shape of the front of this fish's snout resembled a beak, hence the comparison to modern parrotfish, although these animals are not related to each other,” Tyborowski said.

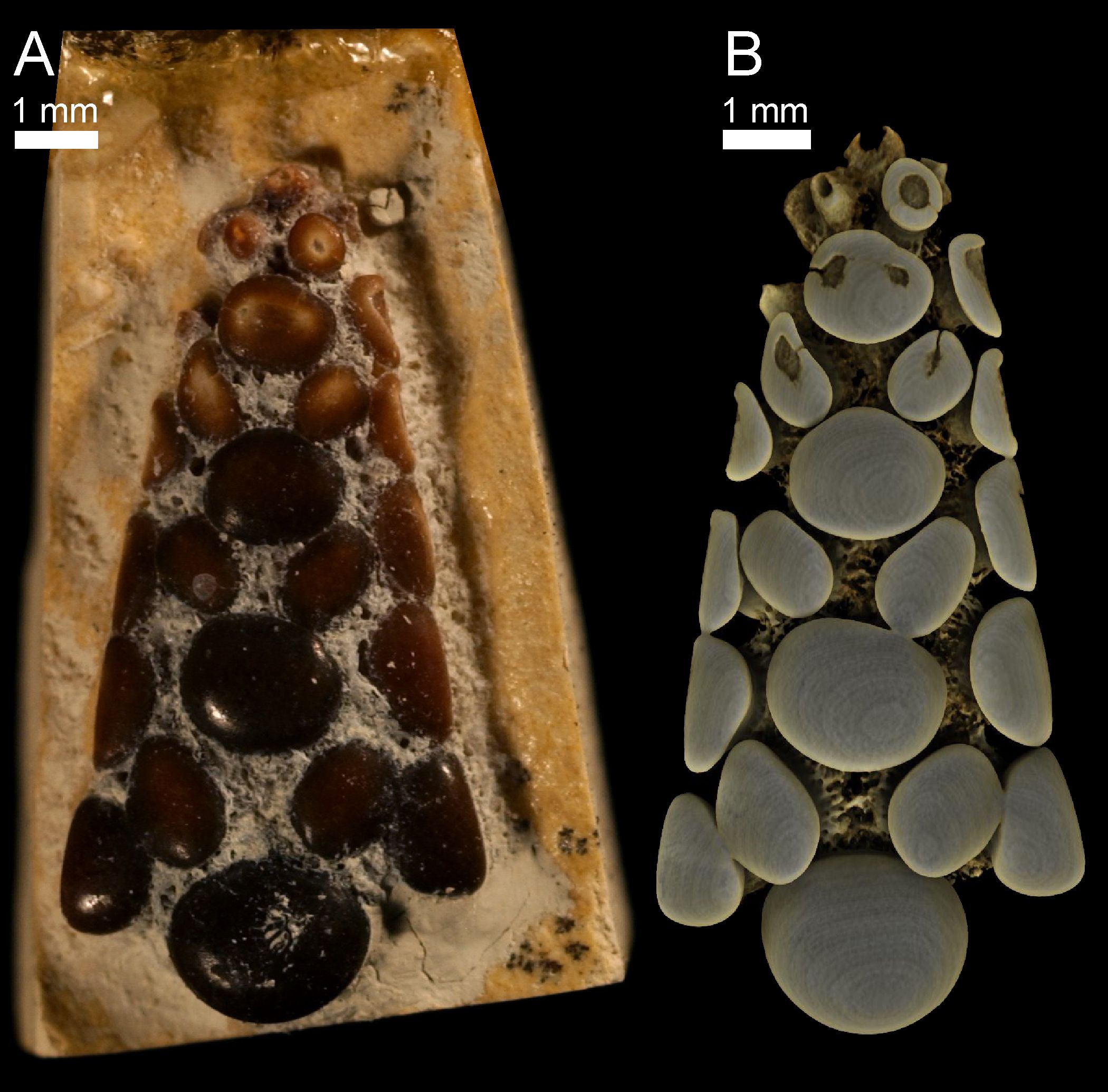

One of the defining traits of pycnodonts was their distinctive teeth—broad, flat, and shaped like buttons or gravel pebbles. This specialized dentition was an adaptation for crushing hard-shelled prey.

“This structure of the dentition was an adaptation to feeding on hard prey,” he said. “The diet of pycnodonts included bivalves, snails, sea urchins, brachiopods, crustaceans, and even other fish. The flat and extremely resistant teeth acted like millstones, which crushed and ground even the hardest prey into a fine pulp. Advanced jaws of these fish, to which powerful muscles were attached, helped to devour hard prey. Flat teeth and strong jaw bones meant that even the most armoured animals had to be on their guard against pycnodonts.”

To further examine the fossil, the team conducted microtomographic (CT) scans of the jaw structure. The scans revealed surprising differences in tooth density across the jaw.

“The teeth from the back of the upper jaw were characterized by a much higher tissue density than the teeth from the front of the mouth,” Tyborowski said. “This means that the fish mainly used teeth located deep in the mouth to crush their prey.”

The finding contrasts with previous studies of pycnodont fossils from Germany, where front teeth in the lower jaw exhibited higher density. According to Tyborowski: “We are therefore dealing here with opposite specializations of the lower and upper jaw dentition.

“Using the back teeth to crush prey seems to make more sense because an increase in the size of the teeth towards the throat is observed in most pycnodonts. Perhaps a kind of asymmetry in the functioning of the chewing apparatus evolved in this group of fish.”

The results of the study, co-authored by Tyborowski and Weronika Wierny, an expert in reconstructing fossil environments from the Polish Geological Institute – National Research Institute, were published in the journal Geological Quarterly.

The researchers plan to continue investigating additional fossil material from the site, where numerous other pycnodont remains have been uncovered.

PAP - Science in Poland

akp/ bar/ amac/