Poland is home to dozens of rare and remarkable minerals, from shimmering sapphires and gold to radioactive autunite and toxic arsenopyrite. According to Bartłomiej Kajdas of the Jagiellonian University’s Natural Education Centre, many of these unique geological specimens are found in only a few places in the country - and some are known mainly from century-old reports.

“You need to know where to look and what to expect,” Kajdas told the Polish Press Agency (PAP). “Poland has several regions that stand out due to their wealth and variety of minerals. In the rest, even an expert might find nothing but ordinary sand.”

Sudetes - the mineralogical capital of Poland

Lower Silesia, especially Sudetes, is considered to be the most geologically diverse region of the country. 'You can find garnets, topazes, beryls, corundum, aquamarin or tourmaline there. Most commonly we find black, opaque tourmalin crystals, but there are also rubelites with an intense pink colour', Kajdas says.

Sapphires, once found in the Giant Mountains, are now rare, but their deep blue colour made them sought-after, even if not suitable for jewellery, he adds.

Radioactive and toxic finds

In the Kletno region, secondary uranium minerals like autunite and torbernite still appear in colourful layers, remnants of old uranium mines. While short-term exposure is not dangerous, Kajdas warns that long-term contact should be avoided.

Another hazardous mineral is arsenopyrite, an iron-arsenic sulphide found near Złoty Stok. It is toxic, especially when eroded or heated. The local gold deposits, historically associated with arsenic, are the reason behind the town’s name, which translates to "Golden Slope.”

Kraków region: Agates and the legendary hatchetin

In Lesser Poland, the Kraków area yields amethysts, chalcedony, and local agates, particularly around Rudno, Alwernia, and Krzeszowice. Rudno’s Agate Museum displays only regional specimens.

The area is also home to one of Poland’s most mysterious minerals: hatchetin. This natural paraffin was discovered over a century ago in Kraków’s Bonarka quarry. “Most collectors only know it from stories,” said Kajdas. No new specimen has been found in 100 years, though several are housed at the Jagiellonian University.

Świętokrzyskie Mountains: Ancient Mines and Striped Flint

Southeast of Kraków, in the Świętokrzyskie Mountains, malachite, azurite, and lead ore (galena) can still be found in areas like Miedziana Góra and Miedzianka — regions that supported medieval mines.

Krzemionki Opatowskie, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is home to striped flint deposits. Used in toolmaking as far back as the Neolithic period, Kajdas said: “It was a strategic raw material. Tools from this flint have been found up to 650 km from the place of extraction.”

Carpathians and the “Maramureș Diamond”

Though less mineral-rich, the Carpathians conceal occasional surprises. Near Rabe in the Bieszczady Mountains and parts of the Beskids, collectors can find the so-called “Maramureș diamond”, a transparent quartz crystal known for its brilliance.

In the Tatra Mountains, black tourmaline can be found, but Kajdas reminds that all collecting in Tatra National Park is strictly prohibited.

Minerals from the sky - meteorites from Pułtusk and Drelów

Poland has also seen multiple meteorite falls, including a historic event in 1868 near Pułtusk. More recently, a meteorite shower occurred in February 2025 near Drelów, Lublin region, yielding over 70 specimens weighing around 4 kilograms.

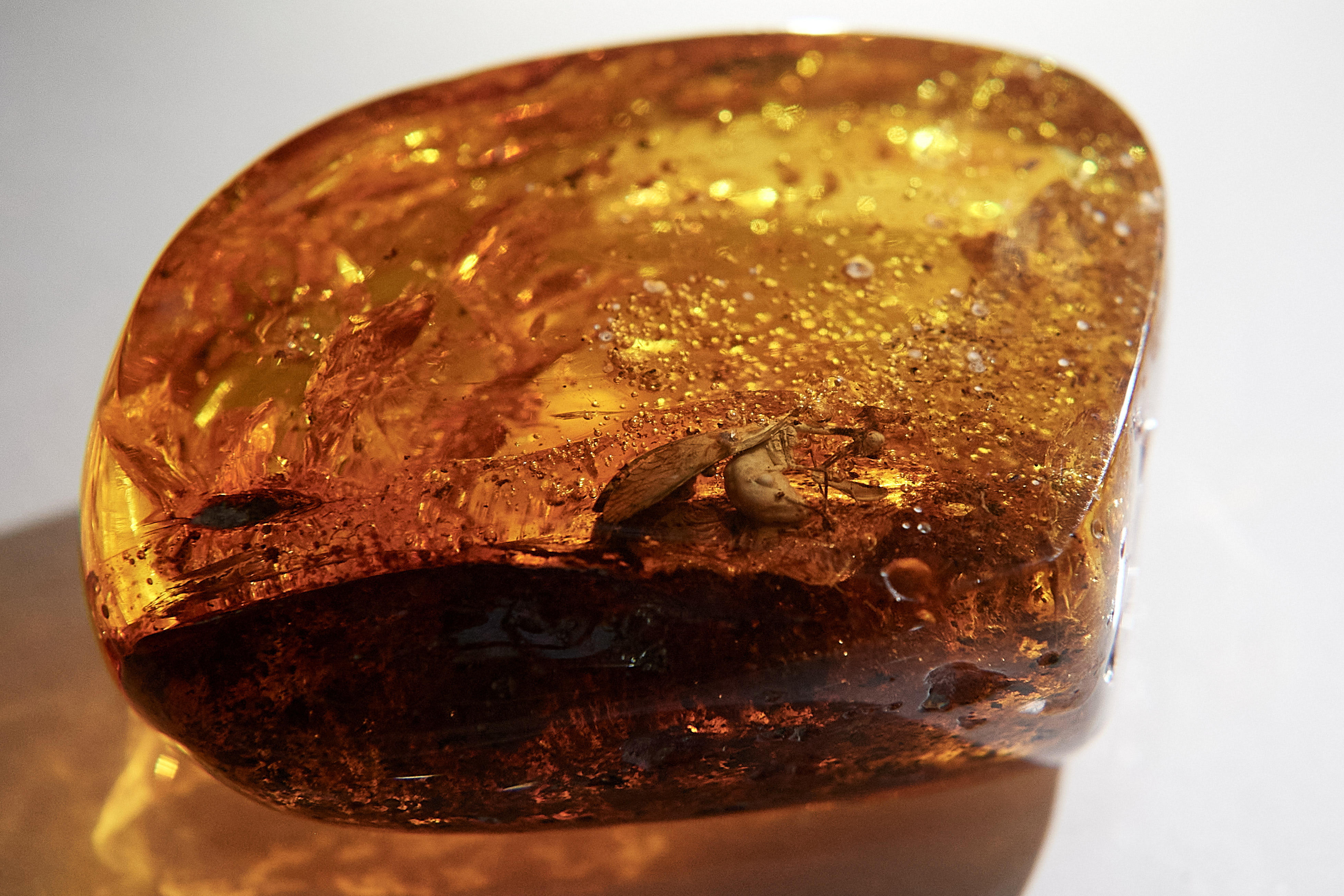

Amber not only on the beaches

Amber, though not a mineral but fossilised tree resin, is also commonly found, not just on the coast, but inland. Kajdas said that the largest amber deposits are found in Eocene-age sandstone layers stretching from Lviv through central Poland to Kaliningrad.

“What washes up on the beaches during storms are fragments dislodged from deeper inland layers,” he said.

“So far, over 70 specimens with a total weight of about 4 kg have been collected. There will probably be a further search at the end of the agricultural season,” Kajdas said.

Know the law and stay safe

Collectors are allowed to pick up stones lying on public land, but digging without landowner consent is illegal. Police have intervened in past cases of unauthorized excavations, particularly in Nowy Kościół and Rudno.

Safety is also a concern. Many of Poland’s minerals contain hazardous elements such as arsenic, uranium, or lead. Kajdas advises washing hands after handling unknown specimens and being cautious with any that show unusual colours or crystal forms.

The best time to search? “Early spring and post-harvest periods are ideal,” he said. “That’s when the soil gives birth to stones.”

PAP - Science in Poland, Katarzyna Czechowicz (PAP)

kap/ agt/ lm/