Mammalian egg cells contain large amounts of energy-storing lipid droplets. Until now, their function was unclear. Now, a team led by a Polish researcher shows that these droplets are necessary in diapause - the period when the embryo waits for the convenient time for implantation.

Egg cells of mammals contain a surprisingly large amount of fat. More precisely: energy-storing lipid droplets. What are they for? The authors of a paper published 30 years ago in Natureshowed that even it these fat droplets were removed from the embryos, they would continue to develop properly. For a very long time, this cellular energy storage seemed to be an evolutionary 'extravagance', an unnecessary burden. This issue bothered embryologist Professor Grażyna Ptak from the Małopolska Centre of Biotechnology of the Jagiellonian University.

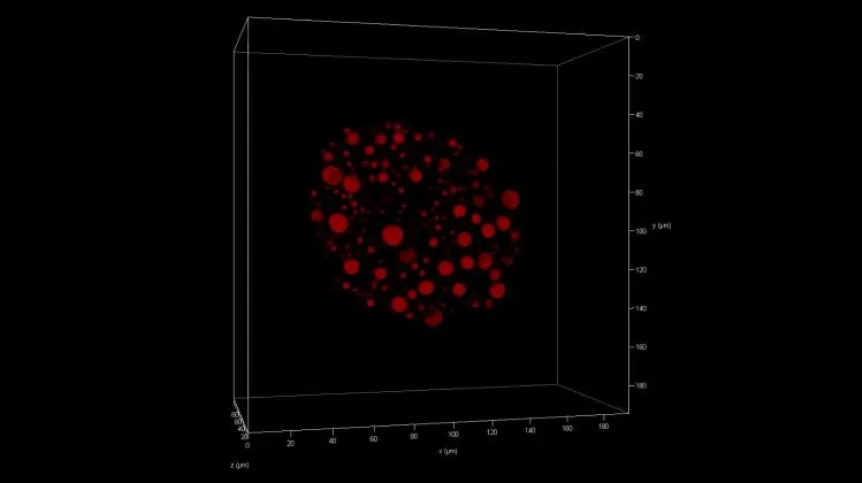

Gif: Visualization shows lipid droplets in a badger's egg cell. Credit: Professor Grażyna Ptak and team

She suspected that this cellular fat storage was only useful under special circumstances relating to the development of the embryo, namely during diapause. Embryonic diapause is the time the embryo waits for favourable conditions for development before implantation in the uterus. Among mammals, diapause is rather rare, it is a standard among only 1 percent of species of mammals. Diapause has not been taken into account in previous studies on lipid droplets.

The idea turned out to be correct. The Polish researcher's hypothesis was confirmed by her team's research, which appeared in the prestigious journal PNAS(https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2018362118).

Professor Grażyna Ptak told PAP what diapause looks like in various species of animals. For example, in a roe deer, if fertilization occurs around July, the embryo waits until winter - the time when the day begins to get longer. Only then does the embryo receive a signal from the mother that it is time to be implanted in the uterus and that pregnancy proper is about to begin. Thanks to this, the young are born in spring, and not in winter, when the survival of newborn deer would be at risk. In roe deer, the diapause can lasts five months.

In the case of a badger or an ermine, the embryo can 'wait' twice as long for implantation. But in mice, the diapause is much shorter and lasts a few days at most. It occurs, for example, when the female is fertilized during lactation, while she is still feeding the young. And then the conditions for the development of the embryo are not yet optimal. So the embryo goes into 'stabd-by mode' for a few days, waiting for a signal from the mother that it can develop.

Some species of mammals have diapause in the reproductive cycle. There are also those that use it very rarely, only when necessary which Ptak says “is a protective mechanism that protects the mother and the young to increase survival rate.”

The team from the Małopolska Centre of Biotechnology checked whether the number of lipid droplets in the eggs of various mammals depended on the length of the diapause. They found more lipid droplets were in the egg cells of those mammals capable of a longer diapause (badgers, ermines, roe deer), and less in the species capable of only a short diapause (mice, guinea pigs, hedgehogs).

GIF: Visualization shows lipid droplets in a mouse egg cell. The diapause in mice is much shorter than in badgers. Therefore, the embryo does not need large energy reserves. Credit: Professor Grażyna Ptak and team

In addition, the team has proven in mice that when lipid droplets are removed from an egg cell and then diapause is forced, the embryo will not survive which Ptak says “nobody has shown before.

“We have shown the role of lipids in early embryonic development. We have also explained why the embryos of various mammals differ in the content of lipid droplets.”

GIF: Removal of lipid droplets from a mammalian embryo makes it impossible to survive the diapause. Credit: Professor Grażyna Ptak and team

The research was financed with a grant from the National Science Centre.

PAP - Science in Poland

Author: Ludwika Tomala

lt/ zan/ kap/

tr. RL