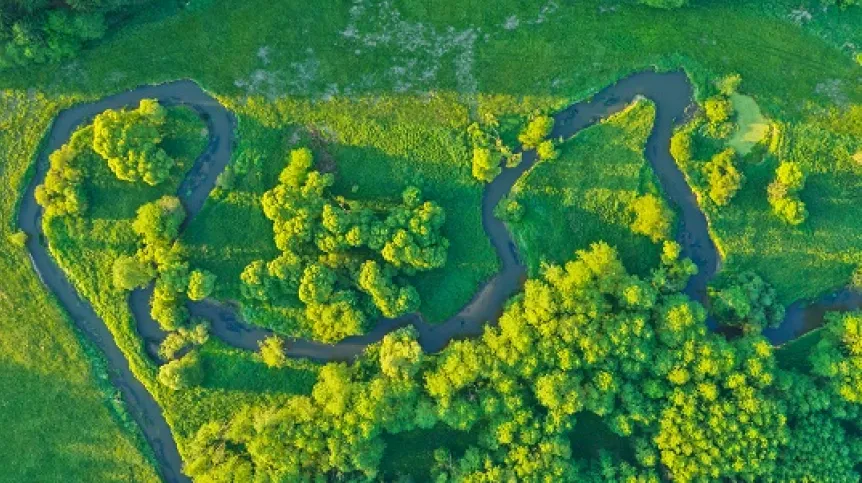

To counteract drought in Poland, we should protect and restore wetlands on the largest possible scale. 'Give wetlands back their space. They are natural water storages in the environment', says Ilona Biedroń from the Wetland Protection Centre and doctoral candidate at the Institute of Technology and Life Sciences - National Research Institute in Falenty.

Poland has small water resources due to its geographical location and the resulting variable hydrological conditions. It has one of the last places in Europe in terms of water resources and is considered to belong to a group of countries at risk of water deficit. We often read that Poland has the same amount of water resources as Egypt. But although the water resources of Poland, Egypt and Alpine Switzerland are similar, the way these resources are shaped is completely different. The main factor on which the amount of water resources of our country depends is the volume of precipitation.

“Transformation of rivers and river valleys may worsen the effects of drought. In turn, the removal of these transformations through the renaturation of surface waters can mitigate the effects drought', says Biedroń whose doctoral research concerns the hierarchy of areas threatened with drought and proposals to mitigate the effects of drought.

Biedroń emphasizes that for counteracting drought and drying rivers, wide public awareness is important, for example concerning water circulation in nature and the role of rivers and wetlands. 'We also need to know what we lose when we transform them', the expert says.

Understanding the role of wetlands can facilitate the implementation of various measures to increase landscape retention. The idea is to retain water in nature, in places where it falls to the ground in the form of rainfall and, slow down the drain through river systems. 'It all boils down to ensuring that the water circulates in nature as long as possible and goes to the sea as late as possible', she says.

This can be achieved with renaturation based on nature. What is river renaturation? 'When an ecosystem has been degraded, damaged or destroyed, renaturation supports the reconstruction of its earlier state or natural processes that used to occur in it', says Biedroń.

She adds that in Poland, the greatest need for renaturation concerns rivers and their valleys - 'such measures are needed in the case require of 91 percent of surface waters, i.e. rivers, which are the basic units of water management, as well as 85 percent of dry peat bogs and 40 percent of degraded lakes.’

Rivers and their floodplains, peat bogs and lakes are the main inland wetland areas. Their renaturation includes 're-watering' wetlands and returning their original space to rivers so that the river flow freely, without hydrotechnical structures, in contact with the flood valley, underground waters and with a natural flow variability, she says.

A drainage agricultural and forestry economy has been widely carried out for decades in all of Europe, leading to the drainage of extremely valuable peat bogs. In Poland, peat bog drainage led, among other things, to losing over 5 billion m3 of water per year, or increasing the annual greenhouse gas emissions by an equivalent of over 33 megatons of CO2.

Biedroń says: 'To this day, it is widely believed that to facilitate the economy and development of cities, towns, villages (including flood protection), it is necessary to regulate rivers and make them drain water quickly during the flood to prevent their water from leaving the riverbeds.’

She adds that straightened riverbeds effectively drain excess water from the ground both during heavy rainfall and floods and during drought, which quickly leads to very low water levels, and small watercourses dry out.

Biedroń continues: ’By straightening riverbeds and building levees, we limited the retention capabilities of watercourses and their valleys. The water in the river flows faster, causing a decrease of the riverbed bottom, and thus - a lower level of groundwater near the river. As a result, river valleys dry faster.’

Another problem is the urbanisation of river catchments - areas from which the water supplies the river, which causes faster water flow on the surface and limits natural retention. As a result, Biedroń says, groundwater resources can become drained and difficult to renew. And yet it is underground waters that supply the river water during the periods without precipitation.

She adds that in transformed river catchments and heavily changed rivers, floods are more rapid, and low water levels are getting more and more severe.

'In addition,’ she says, ‘rivers with straightened beds, without sequential shallow landforms (riffles) and depths (stream pools), without meanders, deposits, point bars and islands, coastal clusters of trees and thickets, coastal buffer zones, are more susceptible to pollution. And yet they receive both wastewater and agricultural pollutants flowing from the fields. River in good natural condition clean themselves well. Naturalists and scientists proved this in the case of the naturally preserved section of the Central Vistula during the Czajka sewage treatment plant failure in Warsaw.’

Biedroń believes that renaturation activities are not common in Poland and are usually carried out by entities working for nature protection, often as part of work related to a specific project, usually the European LIFE programme. As an exemplary measure, the representative of the Wetland Protection Centre names the LIFEDrawa2 project implemented by the Regional Directorate for Environmental Protection in Szczecin. 'It involved restoration works on the scale of the catchment, and not just in specific spots. One of the key activities in this project was raising in the bottoms of riverbeds by laying gravel prisms, which also serve as spawning grounds for fish. These are non-investment activities - and effective ones, as evidenced by the monitoring of implemented activities', she says.

'Unfortunately, these measures do not fall within the definition of river maintenance included in the Water Law, which means that they are not a common and universal practice of water administrators. Such activities have been carried out recently by WWF Polska and PZW Lublin. This is one of the simplest and basic renaturation activities. The WWF Polska Foundation was also the initiator and participant in the first - and so far the only - case of moving flood embankments away from the Oder on the Wojanów - Tarchalice section.'

As a different example, she mentions the renaturation of the urban section of the Mleczna River in Radom or gradual restoration of wetlands in the Kampinos National Park.

'However, these activities are incidental, and the scale of needs - huge', says Biedroń. 'It also happens that after renaturation activities are completed, water administrators revert to standard maintenance practices - deepening, desludging rivers, dead wood removal. Then the effects of renaturation may go to waste. Maintenance activities on the Drawa and its inflows are an example.'

In Biedroń’s opinion, in Poland there is a need to 'change the approach to river management along their entire length - on the scale of the catchment, so that their condition can improve instead of deteriorating'.

In 2018, at the request of the Ministry of the Environment, the Catalogue of Good Practices in the Area of Hydrotechnical and Maintenance Work was developed. 'The idea of good water management practices should become an obligation, not just a recommendation. Good planning and proper management of the river (and its catchment) determine its condition and sensitivity to extreme phenomena, including drought,’ Biedroń says.

It is estimated that 91 percent of river surface waters in Poland could be subject to renaturation, reminds Ilona Biedroń. 'This value results from analyses conducted during the development of the National Surface Water Renaturation Program commissioned by the State Water Holding Polish Waters. Unfortunately, the needs of this program have not been reflected in the subsequent updates of water management plans. Several renaturation measures were proposed in the projects of these plans developed on the scale of river basins, but they mainly focused on removing barriers for fish migration. These measures will not help us improve the amount of water in the rivers,’ says Biedroń.

She also says that the main problem related to renaturation is social lack of understanding, even 'reluctance to take renaturation measures'.

'This is because they require returning space to wetlands, areas that often have already been developed. There are also no tools in Poland to support such activities, e.g. permanent subsidies for land owners, allowing their meadows to be periodically flooded by rivers.’

She adds that in plans developed to reduce flood risk or the effects of drought 'we find a number of new investments, such as reservoirs and flood embankments, which from the point of view of water protection will constitute further transformations. Highly expensive investments can move the problem to another area of the catchment or cause a completely new problem resulting from the change in existing hydrological conditions.

'We lack a comprehensive, coherent approach to water management at the catchment level. Plans should be made based on an in-depth analysis of the causes of problems - and the needs of all users of water, including nature. Instead, we often focus on one aspect and propose quick solutions, most often investments. And renaturation activities often do not involve the restoration of the +natural+ state - but the activities that are conducive to this restoration. That is why we will often have to wait many years for the effects of renaturation. Nature, like a human, needs time to regenerate. The more transformed the river is, the longer its +reconstruction+ can take.’

She says that the renaturation of rivers on the scale of the entire catchment has already been carried out in many places, for example on the Skerne in northern England. The edge embankment (the effect of accumulating of the river sediment from desludging) was removed, deflectors (objects directing water flow) were made and local narrowing of the riverbed was left untouched. 'As a result,’ she says, ‘there was less flooding and the outflow of low waters slowed down. Biodiversity and landscape values for this area were also significantly enriched.

'Renaturation activities also include removing unnecessary partitions, like on the lower section of the Pärnu River in Estonia. The demolition of the dam in Sindi is a great example of the removal of a barrier that lost its original function and was an unnecessary transformation of the river. As for the city river, an example the Izara River in Munich, where the coastal areas are currently the axis of the tourist product and a place of refreshment for residents'.

She continues: ’We should not use it for watering gardens - neither municipal water nor the water from home wells. We should use rainwater. Give up a part of the lawn and replace it with drought-resistant flower meadow. Limit the felling of forests! Evapotranspiration (evaporation from the ground and plants) is a key process in the small water circulation in nature. The more water evaporates this way, the more of it will come back from the atmosphere at a later time. Tree clusters reduce by the wind speed (which limits wind drying) and keep water in the ground. These are activities that we can have a direct impact on.’

She also points out that the main goal should be the protection and restoration of wetlands on the largest possible scale. 'They are natural water storages in the environment' she says. The goals and activities for the next 10 years in this area were defined in the Wetland Protection Strategy in Poland for 2022-2032, developed by the Wetland Protection Centre for the General Directorate for Environmental Protection. Another project supporting this goal is WaterLANDS, the project that involves large scale restoration of wetlands throughout Europe.

'Only if the effectiveness of renaturation measures is insufficient, they should be supplemented with investments such as the construction of retention reservoirs. But this should be the last resort. A retention reservoir built on a river will not alleviate the problem of lack of water in nearby fields, and only a limited number of users will benefit from the accumulated resources', says Biedroń.

She adds that the current practice of 'coping' with drought in Poland mainly focuses on investments in riverbeds. But 'these measures are very expensive, not to mention the high environmental costs. These investments are usually negatively affect the environment'.

Ilona Biedroń is, among others a co-author of expert opinions, studies and plans in the area of water management. She coordinated and managed projects implemented for water administration in Poland (including 'Development of the National Surface Water Renaturation Program'). She is also a co -author of publications on water issues, including those devoted to good water management practices and surface water renaturation. At the Wetland Protection Centre, she is the WaterLANDS project coordinator.

PAP - Science in Poland, Anna Mikołajczyk-Kłębek

amk/zan kap/

tr. RL