Scientists from the Polish Academy of Sciences have developed a key for identifying the talons of diurnal birds of prey and owls. They presented it in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeol. Their tool can be helpful during the study of bird remains found at archaeological sites.

Three employees of the Institute of Systematics and Evolution of Animals at the Polish Academy of Sciences in Krakow: Dr. Zbigniew M. Bocheński, Dr. Teresa Tomek and Krzysztof Wertz published two papers containing the key to identifying the talons of diurnal birds of prey and owls (HERE and HERE). These are the world's first manuals for the identification of ungual phalanges.

The publications will be helpful in the study of bird remains found at archaeological sites and will make it possible to better use the potential associated with the study of talons.

Quoted in a press release, the scientists said: “Imagine the following scene: a cave, about a hundred thousand years ago, inhabited by Neanderthals. One of them, holding a large talon in his hand, makes incisions in it using a sharp flint. Then he inserts a tendon from a hunted animal into the incisions, ties a knot, dyes it with ochre and a pendant is made. Or, imagine a modern man from several or tens of thousands of years ago drilling a hole in an equally large talon with a flint drill.”

Talons were used for decoration or as symbolic objects all over the world, in different eras and cultures. They were already valuable to the Neanderthals, as evidenced by incised specimens found in present-day France, Italy and Croatia. Bird talons were used as pendants in such remote regions of Europe as present-day Romania, Estonia and Sweden. Their peculiar clusters are known from many Neolithic sites in Israel, Lebanon and Syria.

The scientists said: “Identification of bird talons found in an archaeological context can be crucial for interpreting a given site, and especially for analysing the habits and beliefs of the ancients. Only by knowing the species from which the talon had been obtained can we see whether the specimen was obtained from birds living locally or perhaps brought from a distant location.

“We can draw possible conclusions regarding the seasonality of hunting and human presence in a given area (was it a breeding or wintering species?). Did people choose certain species for their amulets and decorations, or were they more opportunistic (versatile - PAP)? What features did these species of birds have in common? Were they nocturnal (owls), actively hunting (e.g. eagles) or were they scavengers (e.g. vultures)? Are there any differences in the selection of species from which talons were obtained for different purposes by different groups of people?

“Many similar questions can be asked, and an experienced researcher will surely be able to draw interesting conclusions from this material, provided that the talon can be identified with sufficient accuracy.”

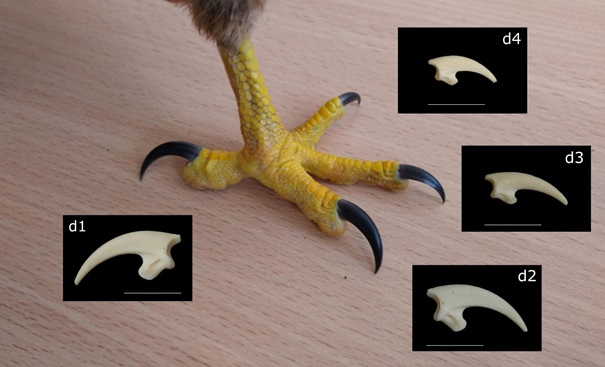

The researchers point out that although few elements of the bird skeleton have as much cognitive potential in archaeology as talons, the correct identification of the bird species from which a given talon comes poses many problems. Birds have four toes on each foot, the talons of which vary in size and morphology. An additional difficulty is the frequent sexual dimorphism in size in diurnal and nocturnal birds of prey (females are larger than males).

Proper identification requires access to a rich osteological comparative collection. One of the largest such collections in Europe is located at the Institute of Systematics and Evolution of Animals of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Kraków.

PAP - Science in Poland

zan/ kap/

tr. RL