Monumental structures dating back 7,000 years and reaching over 100m in diameter, consisting of circular ditches and palisades, remained unknown in Poland until the 1990s. It has been 25 years since the discovery of the first structure of this type, sometimes referred to as the 'Polish Stonehenge'. To date, approx. 20 of them have been identified.

Archaeologists refer to these types of structures as roundels. For a very long time it was believed that they were erected in the area of Europe limited to present-day Hungary, Austria, Czechia, Slovakia and Germany. They were created in a relatively short period, between 4,850-4,600 BCE, in the Neolithic period.

Due to the concentric structure of ramparts and ditches, they are sometimes compared to Britain's Stonehenge. However, that structure is about 2,000 years younger and also consists of huge boulders, while roundels consisted of palisades made of wood. The function of these objects was also probably different.

'We recently had the 25th anniversary of the discovery of the first roundel in Bodzów (Lubusz Province). Although it had remained the only known example of such a structure for many years, today we know that they are much more common,’ says Dr. Mirosław Furmanek from the Institute of Archaeology of the University of Wrocław, who is the discoverer and researcher of several structures of this type.

The first roundel in Poland was located from a plane by the German archaeologist Otto Braasch.

'They were certainly an inseparable, important and even fundamental element for the functioning of agricultural and farm communities in Central Europe almost 7,000 years ago, including those that lived in today's Poland,’ says Dr. Furmanek. Roundels were erected by agricultural communities that appeared in the present-day Poland about 500 years earlier, ca. 5,300 BCE.

Dr. Furmanek admits that for a very long time, the prevailing view in the archaeological community was that roundels had not been erected in Poland. 'This was probably due to the traditional belief that the areas north of the Carpathians and Sudetes were a distant periphery in relation to the cultural centres located in the south. Any novelties were believed to reach these areas with a delay, and often in a stripped-down form,’ he says.

According to the expert, the results of archaeological research in Poland suggest that the communities living on the Oder and Vistula rivers had the same origin as their brethren from the Danube, and that they shared the same beliefs and vision of the world.

'There is no question of isolation and delay. The discoveries of more and more roundels once again prove how little we still know about prehistoric communities. Their world was much more complex and complicated than we can imagine based on very incomplete archaeological research results,’ Furmanek says.

The purpose of these monumental structures is still not entirely clear.

The prevailing view in the scientific community is that they served as places of worship and, at the same time, meeting forums for local communities. Researchers also draw attention to their possible use for astronomical observations.

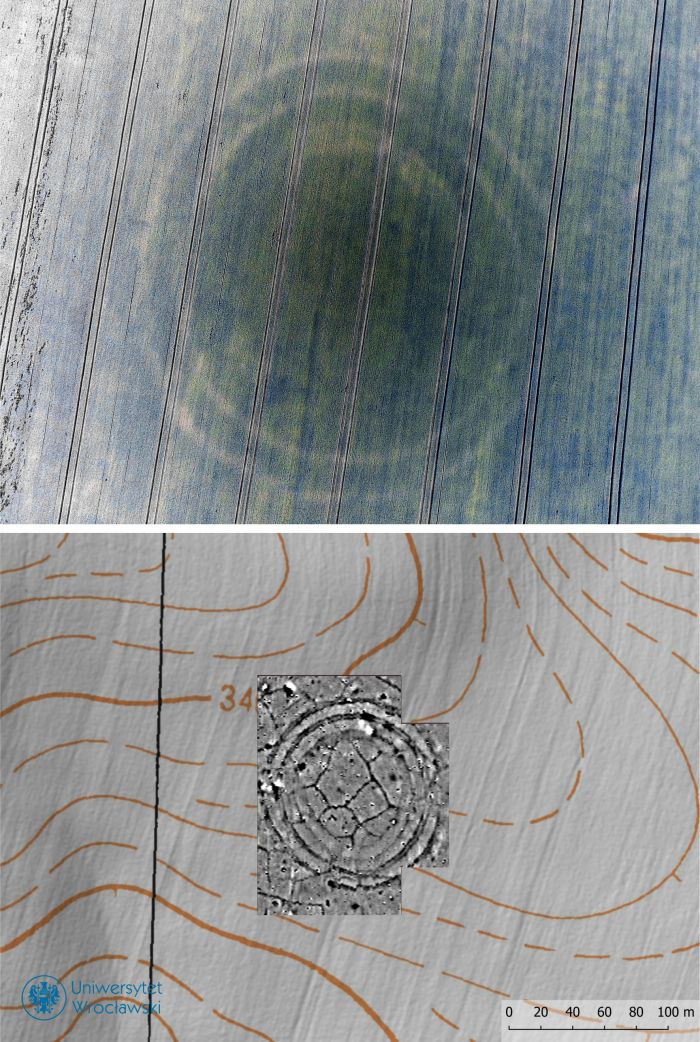

Although there are about 20 structures of this type known in Poland, only two of them have been the targets of extensive excavations - the roundels in Bodzów and Nowe Objezierze. The discoveries were made using non-invasive methods - during the analysis of satellite, aerial or paragliding photos.

'It is difficult to precisely determine their number, because we are not sure whether some of them are actually remains of Neolithic structures. Roundel-like structures with ditches were also built by various communities in later periods,’ says Dr. Furmanek.

Therefore, archaeologists emphasize that the key to determining the age and function of the sites is to carry out excavations or a number of other studies, including non-invasive ones. 'Certainly, their number will gradually increase along with the growing popularity of aerial and geophysical prospecting,’ Furmanek adds.

In Europe, researchers have so far counted about 200 structures of this type. 'We do not see any differences between structures in Poland and those outside our country. This repetition, compliance with certain rules related to their erection and use - was one of the foundations of their existence,’ Furmanek continues.

Dr. Furmanek points out that the research on Polish roundels has brought new information about them.

He says: ‘These structures did not necessarily have to be durable and used for a long time after erection. They could be ephemeral, short-lived objects that were not renovated, but rebuilt instead. Repeated digging and then intentional filling of ditches was probably an important element of the rituals.’

According to him, roundels are also a pretext for many ongoing discussions in archaeology, including those related to social organization and the beginnings of hierarchy.

He says: ’Archaeology is a dynamic science. We live in the time when we can observe with our own eyes the intensive development of methods that allow us to learn about various aspects of the lives of ancient people. Moreover, every year we are surprised by new discoveries.

'Still, we must remember that archaeological data are subject to interpretation based on conscious and sometimes subconscious theoretical assumptions. These interrelated elements shape our ideas about the past, including the Neolithic roundels.’ (PAP)

PAP - Science in Poland, Szymon Zdziebłowski

szz/ zan/ kap/

tr. RL