Dancers in rich costumes and musicians playing drums, flutes and guitars can be found in paintings dating back several hundred years in houses in Chajul, Guatemala.

Polish experts have now summarized a several-year-long project, as part of which they did conservation work on paintings in three houses in the mountain town of Chajul. It is inhabited by the Maya from the Ixil group.

'A few years ago, I was approached by Lucas Asicona, who discovered images of musicians, their instruments, and then dancers dressed in amazing costumes under the layers of peeling plaster in his house. These decorations are still a mystery not only to Lucas, but also to me and many other researchers,’ says project coordinator Professor Jarosław Źrałka from the Institute of Archaeology of the Jagiellonian University in Kraków.

Asicona is a local historian and researcher of the traditions of the Ixil Maya, which is why he also got involved in the project.

Conservation work inside the house of the Zuñiga Family, 2019. The photo shows Aleksandra Nowak, Arkadiusz Maciej, Lucas Asicona, Magdalena Więckowska. Credit: Katarzyna Radnicka.

It turned out that in Chajul there were more mud brick houses with such enigmatic paintings, but only the families living in two other houses decided to let the restorers in. The paintings were mostly covered with a dozen or so layers of whitewash applied over many years.

According to Professor Źrałka, paintings in all the houses are absolutely unique. They were made with a technique and pigments known in pre-colonial times, before the arrival of the Spaniards in the 16th century. However, the depicted motifs are not that old. According to the researchers, they were painted in the 17th-18th century.

'So far, we have known paintings made at that time by local people mainly from churches and convents. That is why they are unique,’ says Professor Źrałka.

The researchers believe that the paintings were made by native artists for local representatives of cofradías, religious brotherhoods that cared for the statues of Catholic saints. These organizations supported the clergy in the newly conquered areas of Latin America and operated like similar brotherhoods in Spain. They operate to this day on both sides of the Atlantic.

'One of the historical documents from the 18th century mentions that in 1740 there was only one clergyman in the Ixil region, based in Nebaj. He travelled and visited individual towns inhabited by the Ixil Maya, including Chajul. Hence the key role of cofradías,’ Źrałka says.

Cofradías were supposed to support the Catholic Church, but according to researchers, many rituals and practices from before the conquista were preserved in the cult of Christian saints.

According to Dr. Monika Banach, a member of a research project from the Jagiellonian University, Catholic saints fit perfectly into local mythology and folklore, coexisting with mountain creatures, and sometimes even taking over their roles. Dr. Banach is responsible for anthropological research and archive studies together with Dr. Victor Castillo, also from the Jagiellonian University.

'Spanish cofradías contributed to the survival of the local worldview, celebrations and dance, and not necessarily to their elimination through evangelisation,’ she says.

The age of the paintings was determined in part based on the analysis of the painted instruments. It was conducted by ethnomusicologists Dr. Igor Sarmientos and Dr. Mark Howell. The figures in the paintings not only play drums, flutes and guitars and dance, some of them, for example, smoke pipes. One of the dancers holds an object that looks like a bottle, probably filled with alcohol. There are also depictions of blooming cacti.

While the paintings themselves lack Christian symbols, such as crucifixes, which are obvious to people of Western culture, altars with figures of saints have been preserved in the rooms with the paintings. Some rooms are also decorated with crosses.

Dancing is an important part of Christian holidays in this part of the world. According to experts, the paintings in Chajul probably show one of them, perhaps the dance of conquest, commemorating the Spanish occupation of Latin America and conversion to Christianity.

The conservation of the paintings was carried out by art restorers Dr. Marcin Błaszczyk (Academy of Fine Arts in Krakow), Arkadiusz Maciej and Tomasz Skrzypiec, as well as archaeologist Dr. Katarzyna Radnicka, with the support of students and doctoral candidates from Poland and Guatemala.

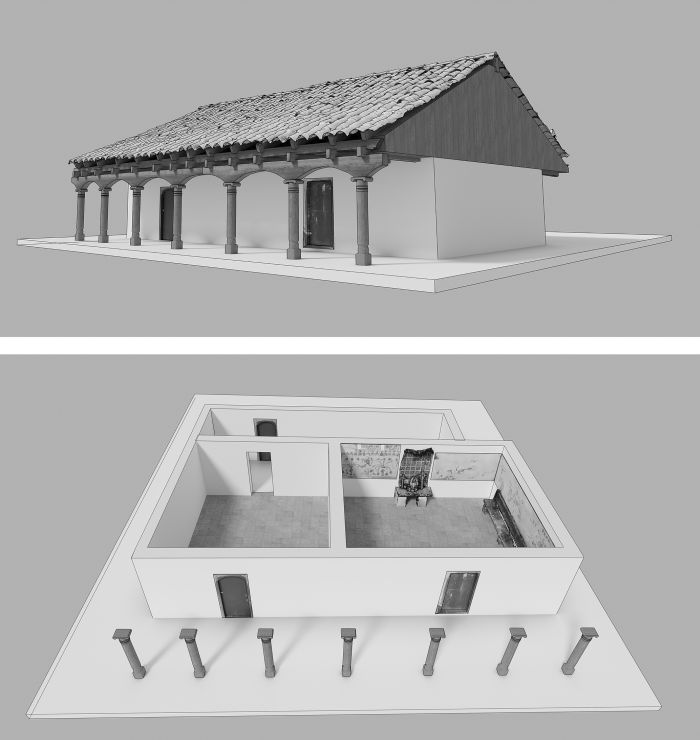

Bolesław Zych and Wiesław Koszkul scanned the interiors of houses with paintings in 3D technology and prepared their digital reconstructions.

Samples of pigments and plasters were analysed by researchers from the University of Valencia - Professor Maria Luisa Vázquez and Professor Cristina Vidal. On the Guatemalan side, the leaders of the research project in Chajul were Juan Luis Velásquez and Evelyn Búcaro.

The project was supported by both private donors and the Polish National Science Centre. It was interrupted by the pandemic, which is why the work started in 2015 was completed only in 2022. The researchers are currently working on a publication on these unusual paintings, which is expected to be published in 2024.

The research in Chajul was carried out with the approval of the Guatemalan Ministry of Culture and Sport.

Szymon Zdziebłowski

szz/ agt/ kap/

tr. RL