The hornet moth (Sesia apiformis) has evolved not only to look like a hornet but also to sound like one, a rare form of mimicry that fools predators into keeping their distance. According to new research led by Dr. Marta Skowron Volponi from the University of Białystok, the moth’s acoustic camouflage is so effective that robins—the study’s test predators—reacted to it almost exactly as they would to a real hornet.

“This adaptive mechanism is a classic example of Batesian mimicry, a phenomenon in which a harmless species evolves to resemble another species with effective defence mechanisms, such as the ability to sting,” said Dr. Skowron Volponi, an entomologist at the Faculty of Biology at the University of Białystok.

The research, conducted in collaboration with the University of Turin and the University of Florence, was published in the journal "Ecology".

The team also described their custom-developed insect audio recording device, the buzzOmeter, in Methods in Ecology and Evolution (DOI: 10.1111/2041-210X.14224).

The project began with a moment of surprise. “I came up with the idea in the field when one of these moths flew very close to my ear,” said Skowron Volponi. “I heard it buzzing just like a bee. It was a revelation.”

Though visual mimicry in moths is well-documented, the researchers wanted to know whether the resemblance extended to sound. “The vast majority of observations and studies on mimicry focus on morphological similarities,” she explained. “We decided to test whether mimicry could also involve other senses, including hearing.”

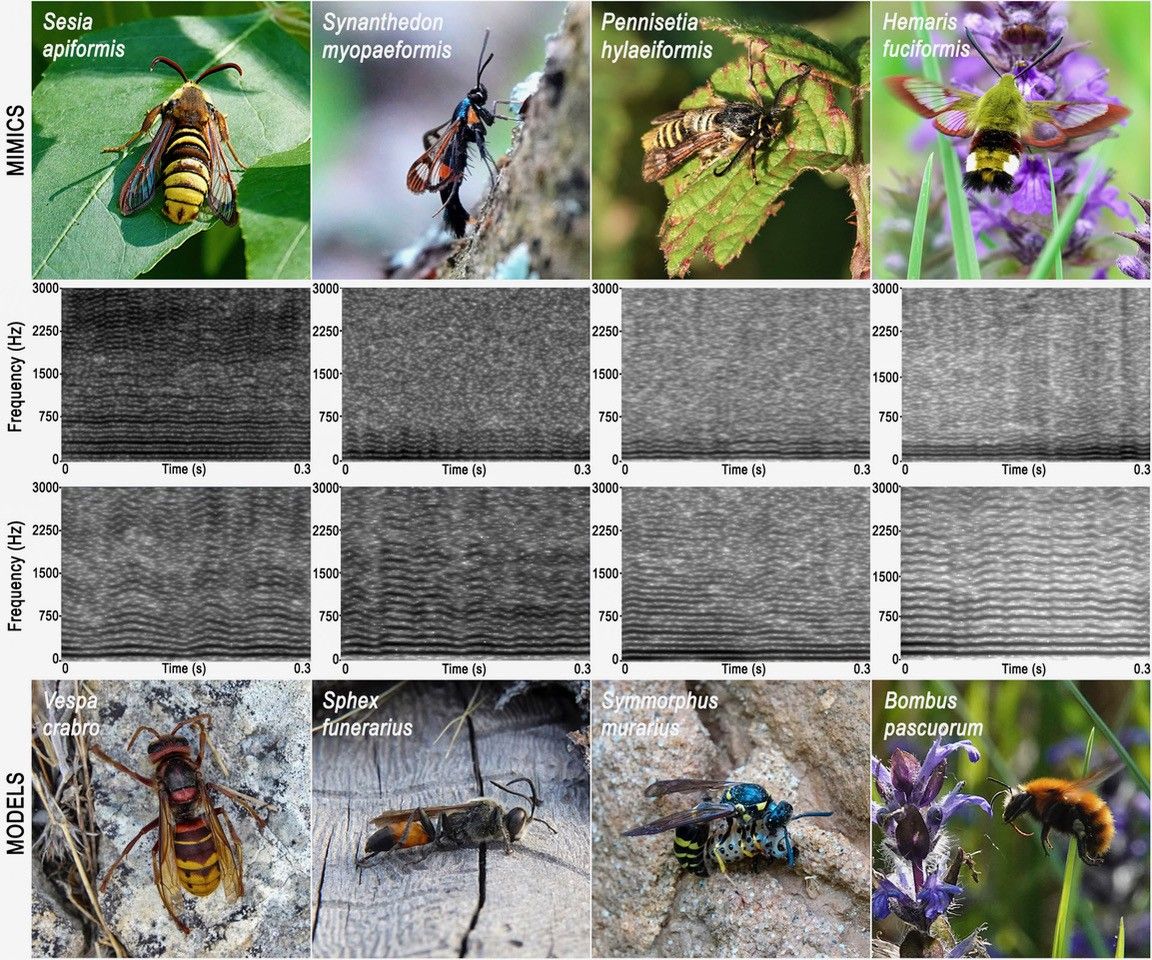

The team recorded the sounds of eight insect species using the buzzOmeter, including four mimic–model pairs—each featuring a moth and a stinging insect it imitates—and a control hawk moth, which does not engage in visual mimicry.

“The analysis of acoustic parameters showed that in the two tested pairs, the sounds were similar enough to indicate acoustic mimicry,” said Skowron Volponi. “The Sesia apiformis, which looks like a hornet and—as we demonstrated—also buzzes almost identically to a hornet, was particularly spectacular.”

To determine if this mimicry worked in the wild, the researchers designed a behavioural experiment involving 21 wild European robins, a species chosen for its curiosity and ease of training in natural settings.

“Most studies involving birds are conducted in captivity,” Skowron Volpini said. “We wanted a natural interaction.”

Each robin was presented with either a mimic moth or its stinging model which was placed on a transparent plate, while a speaker hidden inside the feeder simultaneously played the insect’s buzz.

“The bird thus had the full experience: it saw the insect and heard its sound,” said Skowron Volponi.

The results were conclusive. “It turned out that the robins were most afraid of the hornet and the hornet moth,” she said. “Their reactions to both species were almost identical. The bird was clearly hesitant to approach the feeder and ate significantly fewer larvae. This means that, in the robin’s assessment, approaching a hornet moth carries a similar risk to interacting with a hornet.”