Scientists from the Jagiellonian University and the Polish Academy of Sciences examined the teeth of predatory fish from approximately 148 million years ago under the microscope. Based on their research, they have shown that differences in the structure of the teeth were one of the factors that enabled the coexistence of similar species in one area.

The fossils were discovered in the Owadów-Brzezinki quarry, one of the most interesting palaeontological sites in Poland. The site, located in the Sławno commune (Łódź province), is known for exceptionally well-preserved Late Jurassic fossils of marine and terrestrial organisms.

This time, scientists from the Institute of Geological Sciences at the Jagiellonian University and the Institute of Paleobiology at the Polish Academy of Sciences focused on the teeth of large predatory fish from the Late Jurassic.

'We know numerous taxa of bony fish from the Late Jurassic. Jurassic fish were numerously represented by two groups: holosteans (Holostei) and teleosts (Teleostei). The former dominated then, but are a minority today. In turn, the latter dominate today,’ said Łukasz Weryński, a doctoral candidate at the Institute of Geological Sciences.

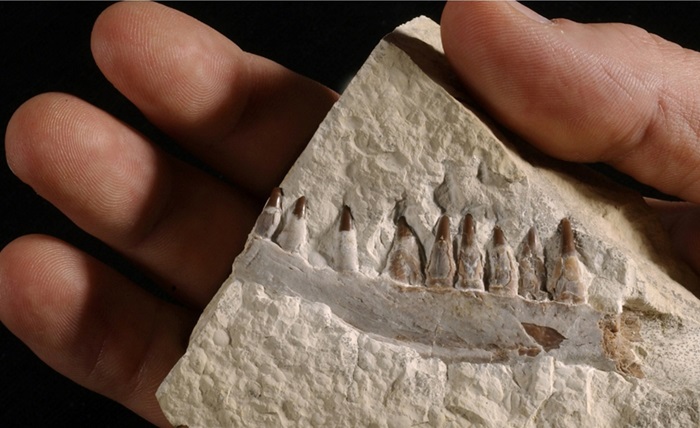

Fossils from both of these groups were found in Owadów-Brzezinki, in a layer of plate limestone, in which fish are well preserved). In the study, the group of holosteans was represented by fossils of fish from the Caturoidea superfamily: the species Strobilodus sp. and teeth of Caturoidea indet., and teleosts by fish from the order Pachycormiformes; Orthocormus teyleri.

'The core issue is that two large predators of similar size (up to 1-1.5 m long) lived in a similar, quite shallow environment. Such coexistence is possible when the taxa occupy different ecological niches, i.e. they perform different functions in the ecosystem and they feed on different food. I assumed that one of the factors enabling this coexistence is the teeth difference,’ Weryński told PAP - Science in Poland.

Scientists decided to verify it with optical and electron microscopes. 'We showed differences in the structure of the teeth of the examined fish. In specimens representingCaturoidea, the teeth were made of orthodentin - a type of dentin with a structure similar to that in humans, which grows 20-30 micrometres per day. However, the examined specimen had irregular growths, which may indicate environmentally unstable conditions. In turn, in Orthocormus tayleri, the internal structure of the tooth is more similar to bone; it is highly vascularised and grows quickly,’ the palaeontologist said.

He added that the shape of the teeth also differed. 'Pachycormiformes had teeth more adapted for gripping and piercing, while the teeth of caturoids were piercing and cutting, evidenced by the presence of cutting edges. The structural differences observed in the teeth help explain how these predatory ray-finned fish could coexist,’ he said.

Weryński added that to his knowledge, this is the first microscopic examination of the teeth of fish representing these taxa. 'Usually, comparative studies of Late Jurassic fish were carried out macroscopically. Our research is the first to compare the internal structure of the teeth using microscopic examination,’ he said.

Find out more in the source publication in Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. (PAP)

PAP - Science in Poland, Agnieszka Kliks-Pudlik

akp/ zan/ kap/

tr. RL