Preparations composed of bacteriophages can be called self-producing and self-limiting drugs: they will multiply as long as they find bacteria. Without bacteria, they will disappear, says Professor Alicja Węgrzyn from the University of Gdańsk. In her opinion, bacteriophages have the potential to save humanity.

PAP: Polish poultry farmers have trouble selling their products, especially in the UK, where they are accused of selling meat contaminated with Salmonella bacteria. Meanwhile, you are working on the use of bacteriophages to combat infections of farm animals caused by these bacteria. How can they help fight Salmonella bacteria?

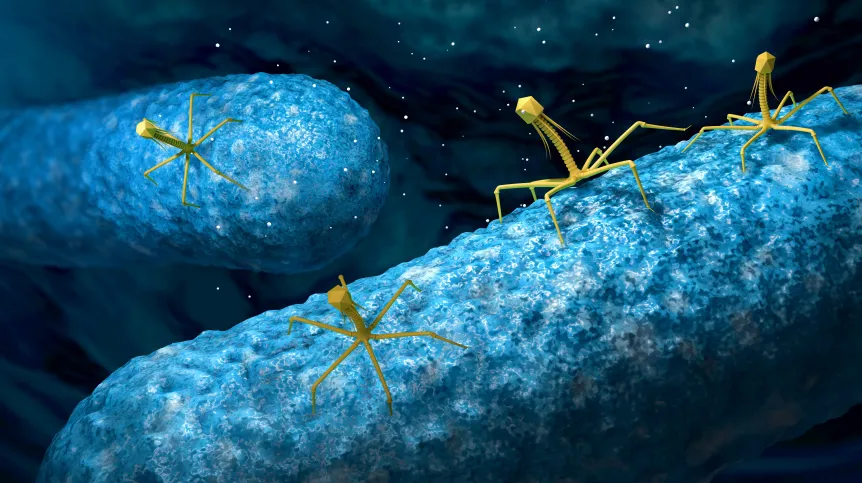

Professor Alicja Węgrzyn, Phage Therapy Center, University of Gdańsk: Salmonella in the poultry industry is indeed a big problem, one that we already know how to deal with using preparations that contain bacteriophages. We will use natural enemies of bacteria found in the environment to fight them. Bacteriophages, or phages for short, are viruses that multiply only in bacterial cells. Each bacteriophage is characterized by high specificity, because most often it multiplies only in one species of bacteria, sometimes even in specific strains.

During the multiplication process, bacteriophages produce enzymes that break down the bacterial wall, simply causing them to burst and release daughter phages (viruses) that can infect further bacterial cells.

PAP: How long will they do this?

A.W.: Molecular biologists like to say that bacteriophages are a medicine that produces itself and limits itself: phages will multiply in a given environment as long as they find their hosts - bacteria. If bacteria disappear, bacteriophages will also disappear because they will not be able to replicate.

PAP: Are they a threat to human health?

A.W.: Our bodies are used to dealing with bacteriophages from birth. Phages pass through the placenta to the foetus, the baby receives them from the mother at birth, and they are also in breast milk. Bacteriophages are common in our body, mainly in the intestines, where they are part of the microbiome, they are present in the blood and delivered to all organs through it. They can even cross the blood-brain barrier and thus enter the brain.

The human body has been interacting with bacteriophages for millions of years - it's not like they appeared suddenly and during therapy we will be administering something unusual that the human or animal body has never come into contact with before, so we would expect a spectacular reaction. The body will accept them calmly and gratefully, unless there are any impurities in the preparation (which results from human activity). What's more, their presence in our body is essential: our health, not only physical but also mental, depends on their quantity, diversity and presence in our intestines.

PAP: Back to our poultry farmers and their problem - have you already developed a method of administering these bacteriophages to chickens?

A.W.: Yes, they can be administered in several ways. Bacteriophages may be included in strictly medicinal preparations, but since Salmonella bacteria cannot be treated, in this case they may be preparations that will prevent infection and have a prophylactic effect. For example, you can add them to water or use them to fog rooms. In birds, there are two ways of entry of pathogens: through the respiratory system and the digestive system, in the case of bacteriophage mist, poultry will simply inhale it. Other pathogens, for example the Escherichia coli bacterium, can also be eliminated in the same way.

Bacteriophages can also be used to prepare disinfectant liquids. This will reduce the number of bacteria on equipment or feed and water supply lines. Their use will also reduce the amount of pathogens in the litter.

However, bacteriophages can also be used earlier, namely in the parent flock, protecting laying hens and then eggs. At the end of the production cycle, they can be used in slaughterhouses, and this is an extremely important phase. Imagine a production line made of stainless steel on which Salmonella has formed a characteristic biofilm, a higher-order bacterial structure resistant to antibiotics, disinfectants, ozone, ultraviolet radiation - basically everything we use for disinfection. However, bacteriophages are able to deal with this biofilm.

PAP: This bacteriophage biological weapon is very versatile.

A.W.: It certainly is. It can also be used in storage rooms, in rooms where meat is cut, where, despite the low temperature of -4 degrees Celsius, Salmonella survives and can easily remain for several years. Preparations with bacteriophages will also be useful in the transport phase, e.g. for washing cars, containers, boxes, etc. We can also use them to protect meat or eggs, not only against the development of Salmonella bacteria, but also against other pathogenic bacteria. We have a lot of possibilities, we just need to test everything thoroughly.

PAP: You say we can do this and that - so why aren't we doing it?

A.W.: We do it all the time. However, if we are to use preparations that will effectively eliminate Salmonella, we must prepare thoroughly. We are currently working with nearly 400 different strains of Salmonella bacteria that are found throughout Poland and we are looking for bacteriophages that will work best in their case.

That is why we work with a large pool of bacteriophages, check them and test them. We choose the best ones. For this reason, the work is taking longer, but I think that in two years we will be ready to test the preparations in the field, in clinical trials.

PAP: Where do you get bacteriophages for research and then for the production of preparations?

A.W.: The best source of bacteriophages is municipal sewage, and hospital sewage is an absolutely excellent source. So far, we have not genetically modified them in any way, so they are bacteriophages that occur in nature. We multiply them and test their properties in the laboratory.

PAP: What features are you looking for in bacteriophages?

A.W.: There are benign bacteriophages that can integrate into the chromosome of bacteria, they sit there and wait for good times when the bacteria is well nourished, we call them lysogenic. These are of little use for therapy, so we reject them. We obtain the so-called lytic phages that enter the bacterium, quickly subdue it, multiply rapidly, tear it apart and throw the daughter phages outside. These are the only ones we are interested in - predatory ones. And at the very end of our laboratory work, we isolate the genetic material of selected phages and then sequence it. We need to check whether phages do not carry antibiotic resistance genes or, for example, toxin genes that may be harmful when administered to animals or humans. Only then can we say that we have a collection of phages that we will combine with each other and create phage preparations, technically called phage cocktails.

PAP: You can conduct this research on bacteriophages because you first received a research grant for it, and then you found clients who pay for it. Yet for decades it has been said that bacteriophages can replace and certainly support antibiotics - in the treatment of both animals and humans. There is no need to explain to anyone what a problem antibiotic-resistant bacteria are today, and yet the topic of bacteriophages and the possibilities of their use is not particularly popular.

A.W.: When it comes to experimental treatment of people with phages, one centre in Wrocław does that. Doctors qualify for this therapy, but in fact our doctors' knowledge on this subject is insufficient. In addition, doctors are afraid of using the preparations as part of experimental therapy, i.e. an officially unregistered one. But this may change, because the European Medicines Agency (EMA) has issued a regulation describing the procedures according to which the registration process of preparations containing bacteriophages for animals, i.e. for use in veterinary medicine, is to be carried out - so we already have it. In the case of procedures for registering preparations intended for humans, consultations are underway on the already prepared regulations, so it can be expected that they will enter into force soon.

PAP: Antibiotic producers will not be happy.

A.W.: Definitely, it is a huge, strong lobby that we will probably have to face. However, to be clear - bacteriophages, as medicines, are not perfect either. For example, a preparation consisting of, say, five bacteriophages, will not work forever. This is biology, constant evolution, so bacteria also become resistant to bacteriophages, which means they will evolve to break this resistance. Therefore, it will be necessary to monitor the effectiveness of these preparations and, if necessary, modify their composition.

PAP: Is it worth it?

A.W.: If we can only limit the use of antibiotics and the spread of drug-resistant forms of bacteria in the environment, it will be very profitable. People have made many reprehensible mistakes when it comes to antibiotics; in the 1960s and 1970s, antibiotics were used in huge quantities as a feed additive, not so much for therapeutic purposes, but as animal growth promoters. Meanwhile, the use of antibiotics in low concentrations causes bacteria to become resistant to them. In this way, we have drastically reduced the number of effective antibiotics in both human medicine and veterinary medicine. Antibiotic resistance in the natural environment is a normal thing, but it occurs on a micro scale.

PAP: Will bacteriophages save humanity?

A.W.: I would really like it to happen. They do have the potential.

Interview by: Mira Suchodolska (PAP)

mir/ ral/ mhr/ kap/

tr. RL