The inhabitants of Nea Paphos, Cyprus, produced their own cooking ware pottery. Potters did not put much time into their production, and they made pots and pans in large quantities. Pottery was made of clay, devoid of decorations, and would often break, according to research by Polish archaeologists.

In ancient times, Cyprus was first on the border of Middle Eastern and Egyptian influences, and within Greek civilization from the 2nd millennium BCE. Port cities, including Nea Paphos, had a huge impact on the civilization development of the island. This thriving city was founded at the end of the 4th century BCE. Over time, it became the main administrative and political centre of Hellenistic and then Roman Cyprus (approximately 200 BCE to 350 CE). The favourable location by the sea and close to mountains rich in copper deposits and covered with forest provided easy access to natural resources, such as wood used to build ships; the city also became an important trade centre.

Nea Paphos is currently one of the most important archaeological sites in Cyprus, explored by Cypriots and numerous foreign missions, including Polish ones.

In one of the latest publications on Cypriot archaeology, Dr. Edyta Marzec and Monika Miziołek from the Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures of the Polish Academy of Sciences and Dr. Kamila Nocoń from the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology of the University of Warsaw describe cooking ware pottery used by the inhabitants of Nea Paphos. The results of this research were published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports.

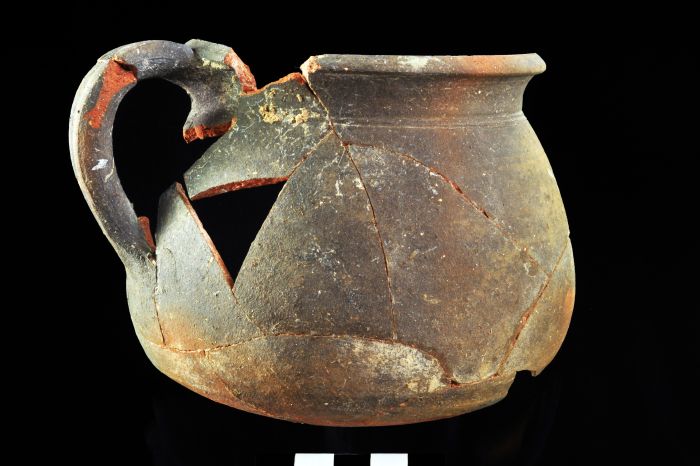

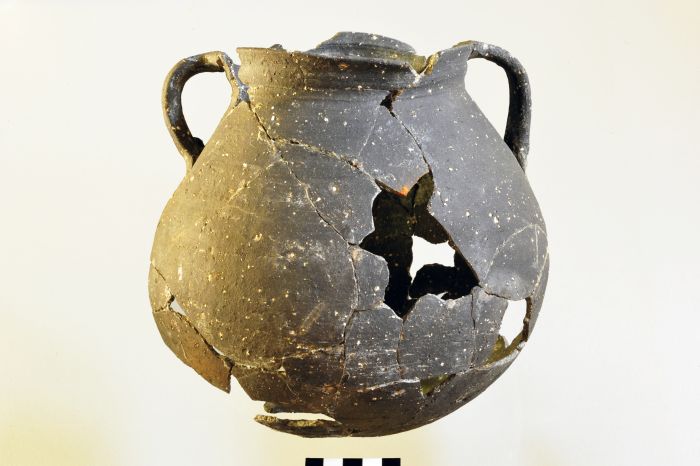

The archaeologists focussed on cooking ware: pots, saucepans, frying pans, jugs, lids. The examined vessels and their fragments came from excavations conducted by the Jagiellonian University and the University of Warsaw at two sites within the city: the Agora and Maloutena, i.e. in the shopping square and in the rich part of Nea Paphos, where residential villas dominated. A total of 136 samples of various types of vessels were analysed.

Dr. Edyta Marzec from the Institute of Mediterranean and Oriental Cultures PAS explains that such data are a source of knowledge not only about local customs and way of life, but also about production places and technology, economic connection networks, and the flow of materials and goods.

The information collected during the research project shows that not much time and effort was put into the production of the vessels and their appearance. 'The vessels were not decorated, only smoothed on the surface. They did not last long, they were thin, so they would break quite often, and they were often replaced. Wealthier residents probably also had metal vessels,’ says Dr. Marzec.

According to the researchers, cooking utensils from ancient Cyprus were quite diverse in terms of shape and ceramic mass; perhaps different potters prepared the clay slightly differently. There were no visible specialisations of specific workshops. The vessels were probably produced outside the city walls because their makers needed a place to dry them and access to water and clay.

Most of the cookware from Nea Paphos was produced locally, only some were imported - both in the Hellenistic and Roman periods. Since the locals had access to materials for making vessels, those made locally were cheaper than imported, mass-produced ones.

'Tradition may also have played an important role. The archaeology of islands shows that although they are connected to the world, they are closed territories. The inhabitants respect their traditions, are conservative and, despite contacts with other cultures, are not so quickly influenced by them,’ Marzec says.

During the Roman period in the Mediterranean, many cities, such as Athens, mainly used imported cookware. 'Back then, there were already centres specializing in almost mass production of, for example, kitchen pots, which were exported everywhere. They were a bit like the Chinese products that flood the market today,’ the researcher says.

One such center producing vessels on a large scale in the early Roman period was Phocaea, located in today's Turkey. According to Dr. Marzec, the pottery from there was of quite good quality and its production was standardized.

Nea Paphos also imported products from Italy. 'Italian cookware is believed to have been transported and used by the Roman army. Despite the absence of Roman legions in Nea Paphos, Italic flat pans have been identified in the city. These vessels were probably used for cooking traditional dishes by the Italics living in Nea Paphos. Cypriot pots were not suitable for this,’ says Dr. Marzec.

The monuments of Nea Paphos have been included in the UNESCO World Heritage List. Polish excavations in this area were started by the father of Polish Mediterranean archaeology, Professor Kazimierz Michałowski. They was continued by the mission of the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology of the University of Warsaw and the Jagiellonian University. The leader of both projects is Professor Ewdoksia Papuci-Władyka. Pottery research is financed by the Polish National Science Centre.

PAP - Science in Poland, Ewelina Krajczyńska-Wujec

ekr/ zan/ kap/

tr. RL