The geometric patterns, lines and zigzags that accompany the images of dancers (danzantes) carved in the rocks of the Peruvian Toro Muerto are not snakes or lightning bolts, but a record of songs - suggest Polish scientists who analyse rock art from 2,000 years ago.

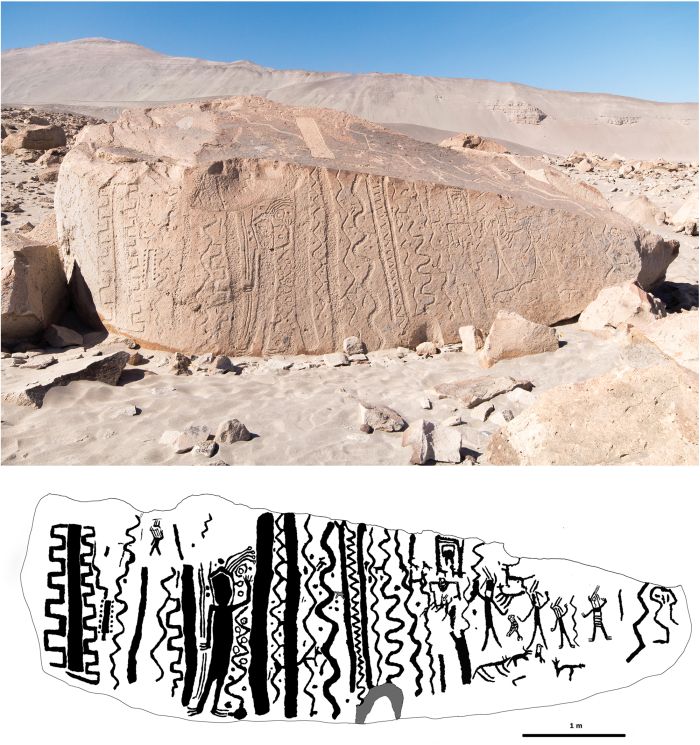

Peru is home to one of the richest rock art sites in South America. Toro Muerto, a desert gorge, is surrounded by hills from the east and west, descending into the Majes River valley. Its central area of approximately 10 square kilometres is full of thousands of volcanic boulders, of which approximately 2,600 have preserved rock carvings (petroglyphs). These range from small stones decorated with single motifs to boulders weighing many tons, with dozens of various depictions on their surfaces. Petroglyphs were created at different times - the earliest ones were probably made by the members of the local Siguas culture approx. 2,000 years ago, and the latest ones possibly by the Incas in the 15th century.

The rock carvings depict mainly zoomorphic motifs (e.g. figures of snakes, wild cats); geometric patterns, most often in the form of vertical zigzags, straight and wavy lines of varying width, sometimes accompanied by dots or circles.

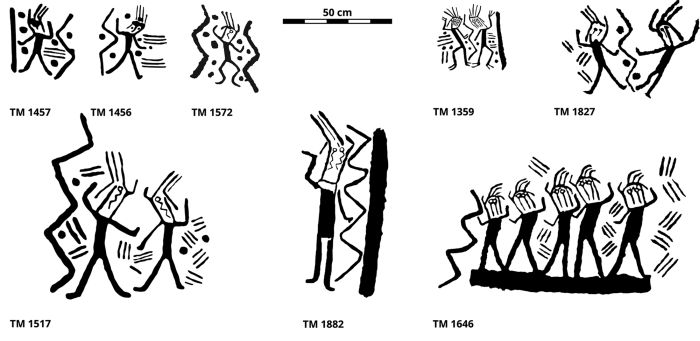

However, unique to the petroglyphs from this place are the drawings of the so-called danzantes - dancers. A danzante is a schematic drawing of a human figure (usually 20–30 cm high). Most often, the figure is depicted in a dynamic pose, with one arm raised and the other lowered, with the legs slightly apart (sometimes bent at the knees), with the head presented on the face or in profile. The figures of danzantes are also accompanied by geometric patterns, lines and zigzags.

So far, the interpretation of these images has been based on analogies with other archaeological sites with petroglyphs in Peru. For example, it has been suggested that these signs may symbolise snakes or lightning bolts; given the desert nature of the place - that they may be associated with heavy rains, water worship or crops.

'It has often been argued that since we are dealing with a desert, the rituals must concern providing water for crops. Meanwhile, ritual places are not only about asking for water or rain and ensuring conditions for survival in the next year. The stories these petroglyphs tell do not only concern the current moment,’ says Professor Janusz Wołoszyn from the University of Warsaw.

Geometric patterns from Toro Muerto appearing separately, as independent motifs, were associated with representations of valleys, rivers, irrigation canals, roads or trade routes, and the accompanying dots or circles with stone mounds placed along communication routes.

Although Toro Muerto has been known to scientists since the 1950s, there has been no consensus among researchers as to the interpretation of the function and meaning of the geometric signs accompanying the 'dancers' in the petroglyphs of Toro Muerto.

Polish-Peruvian research conducted there since 2015 sheds new light on this issue. The research included detailed geodetic and iconographic documentation of the entire site, as well as the first excavations at some boulders.

Now, as one of the results of this research, professors Andrzej Rozwadowski from the Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań and Janusz Wołoszyn from the University of Warsaw propose a new hypothesis regarding the patterns that accompany the dancers on the petroglyphs of Toro Muerto. They presented their conclusions and interpretations in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal.

They suggest that the geometric patterns with which the danzantes are depicted in Toro Muerto may have represented songs. Some of the more complex compositions were graphic metaphors for transition to another world.

'The source of our interpretive proposal is an ethnographic analogy from the Amazon, and more precisely, the art of the Tukano people living on the border of Colombia and Brazil,’ says Professor Rozwadowski.

The art of this people has been quite well documented in ethnography in the form of drawings. The geometry of these patterns has become an inspiration for many rock art researchers.

'Researchers noticed the similarity of its motifs to motifs from other parts of the world. Even Palaeolithic art from caves dating back several thousand years was interpreted on this basis,’ says Professor Rozwadowski.

In Toro Muerto there are also many motifs that are similar to the patterns drawn by the Tukano.

'I began to analyse descriptions of Tukano art again and found that the Indians explained some of these motifs as representations of songs. Considering the accumulation of danzantes motifs in this place, one may ask: what do people dance to? They dance to songs. Once I started putting it all together, it started to fit. It seems that no one had noticed it before, and this interpretative proposal basically suggested itself,’ Rozwadowski says.

Certain sequences are repeated in the compared images from Toro Muerto and Tukano. One of the most important motifs can be described as a battlement, resembling the top of a defensive castle wall in the form of a series of toothed, rectangular projections with openings. Rozwadowski explains that it is described in Tukano's art as a visualization of the cosmos, which can be entered, for example, through a ritual using hallucinogenic substances, the experience of entering a trance, and songs are extremely important in this process.

'This content seems to fit our illustrations very well. Especially those visible on the TM 1219 boulder, which became the key, the gateway to interpretation. There is no other rock in Toro Muerto in which a human figure surrounded by geometric motifs is so well incorporated,’ says Professor Rozwadowski.

'The dancer-zigzag combination appears on hundreds of stones, but only in this case is it such a complex sequence. This boulder is located in such a place that it is impossible not to notice it, and in front of it there is a large space where people could gather and listen to stories or songs,’ adds Professor Janusz Wołoszyn.

'The analogy we used,’ Rozwadowski says, 'leads to the conclusion that the meanings accompanying the images could be fluid and not unambiguous. At one moment, an image could carry a range of meanings. We assume that the motif did not necessarily have to mean what we associate it with most easily, and the cultural context is important,’ he adds.

Find out more about research in Toro Muerto on the website and in the video available on YouTube.

The research was financed with a grant from the Polish National Science Centre. (PAP)

PAP - Science in Poland, Ewelina Krajczyńska-Wujec

ekr/ agt/ bar/ mow/ kap/

tr. RL