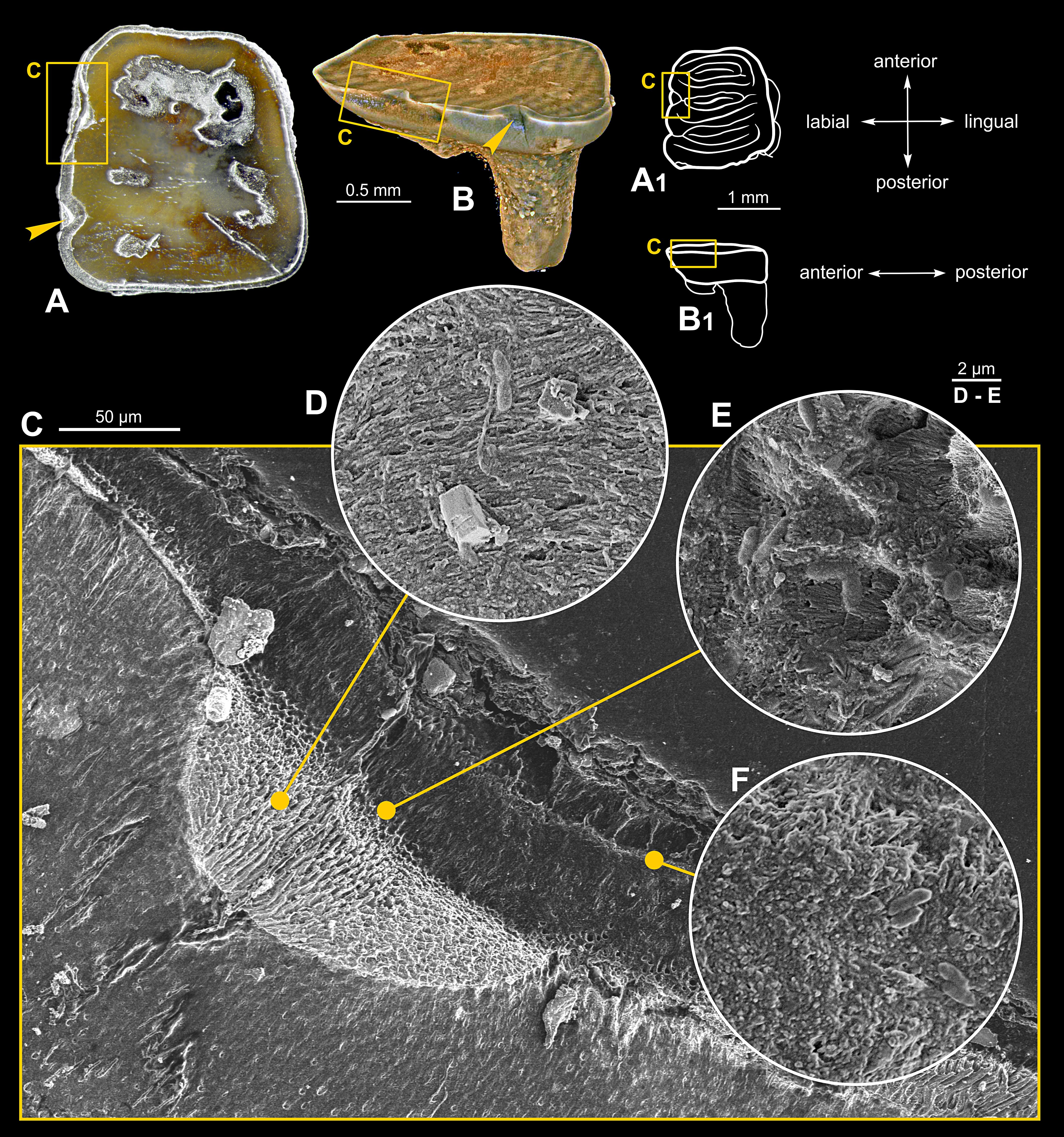

![Tooth of the dormouse Glis sackdillingensis (Heller, 1930) (ZPAL M. VIII/b/G2/1) found at the Węże 2 site. The age of the tooth is estimated at 2.9-2.6 million years (late Pliocene). A. Photograph of the upper grinding surface. The yellow box [C] indicates the region affected by caries. B. 3D model made using X-ray microtomography showing the affected area. A1/B1 tooth diagrams and its position. C. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) image of tooth enamel affected by caries. D, E, F fossilized bacteria with an indication of their location within the defect. Credit: Dr. Błażej Błażejowski.](/sites/default/files/styles/strona_glowna_slider_750x420/public/202407/48970408_48970396.jpg.webp?itok=R-aRJyq5)

Rodent teeth from over 2.5 million years ago were damaged by the caries disease, Polish palaeontologists have found. They noticed traces of the disease along with bacterial remains on a molar of a dormouse.

'The sample is 2.9-2.6 million years old and may be the oldest known case of a pathological dental condition preserved in fossils along with the microbial pathogen responsible for its development. It is a known fact that the problem of caries has been affecting animals for millions of years. We have proven that infections look very similar to today's ones', say scientists from the Institute of Paleobiology at the Polish Academy of Sciences, and authors of a publication on the subject in the journal Acta Palaeontologica Polonica.

The case concerns the tooth of the Pliocene dormouse (Glis sackdillingensis) - a small rodent that lived in the lands of today's Poland over 2.5 million years ago.

'Everything indicates that Pliocene dormice were very similar to modern ones. Modern dormice are small forest animals that resemble a mouse/squirrel hybrid, which mainly feed on fruits and hard seeds, e.g. nuts. Interestingly, the ancient Romans considered them a delicacy. For small rodents, they live a long time, up to nine years', says Dr. Paweł Bącal, one of the authors of the publication, who heads the Electron Microscopy Laboratory at the Institute of Paleobiology of the Polish Academy of Sciences.

The tooth was found in the mid-20th century at the palaeontological site Węże near Działoszyn (Łódź province). It was catalogued, but it took several decades for it to be examined. A few years ago, it was examined by doctoral candidate Michał Czernielewski, Dr. Paweł Bącal and Dr. Błażej Błażejowski.

'The uniqueness of this tooth is that it contains not only traces of the disease (carious defect covering the enamel and dentine), but also probably fossils of the pathogens responsible for causing it (bacteria). This is the only such case known to us in the fossil record. It is also unique because it is the oldest fossil rodent tooth affected by caries', says Czernielewski.

The molar tooth (the size of a pencil tip) was examined using various techniques and methods, including computer microtomography and scanning electron microscopy. 'Based on this, we found the presence of fossilized microorganisms in the cavity, resembling modern caries bacteria. Presumably, these are traces of a disease state along with the remains of pathogenic microorganisms', adds Bącal.

He believes that it was not a 'spectacular hole in the tooth', but caries in the initial stage. 'The tooth was cracked, which weakened it and led to the growth of bacteria. We see that this tooth was still defending itself while it was alive, hence the inflammation present in it', he says.

To explain the origin of this infection, researchers also analysed available data on the dietary and lifestyle habits of modern dormice. 'We believe that the tooth may have cracked while trying to bite into hard food and thus weakened. Moreover, their long lifespan, for a rodent, gave the bacteria time to develop', says Bącal.

He adds that while teeth with caries are known to science, they are extremely rare. ‘Firstly,’ he says ‘they are very susceptible to further degradation and are less well preserved. Secondly, these bacteria are easy to miss during microscopic examination, so in the publication we also describe possible methodological reasons for the lack of similar reports in the literature. We hope that our publication will be of use to other researchers who encounter similar problems and dilemmas'. (PAP)

PAP - Science in Poland, Agnieszka Kliks-Pudlik

akp/ bar/ kap/

tr. RL