A large portion of the human genome is made up of viral remnants, genetic material left behind by ancient infections. New research published in Cell Reports reveals that when these sequences become overactive, they can trigger autoimmune diseases.

The study was conducted by an international team of scientists, including Polish researcher Magdalena Madej, a doctoral candidate at Lund University and the paper's first author.

“This discovery helps us better understand why in some people, the immune system begins to attack its own body. I hope that in the future, these results may facilitate diagnosis and open the way to research on RNA therapies for autoimmune diseases,” said Madej.

Viruses depend on host organisms to replicate, inserting their own genetic material into the DNA of bacteria, animals, plants, or fungi. Over evolutionary time, some of these viral sequences became embedded in host genomes and were passed down through generations.

It is now known that more than 40% of the human genome is composed of mobile genetic elements—including endogenous retroviruses and retrotransposons—many of which have viral origins.

Some of these genetic elements have been repurposed by the body for beneficial functions, while others remain neutral. But some can be harmful, particularly if they interfere with functional genes or activate the immune system.

The recent study demonstrates that the human body has evolved mechanisms to regulate these ancient viral sequences. A key component of that regulation is the enzyme PUS10, which acts as a molecular sentry.

PUS enzymes have long been known to play roles in cellular processes such as protein synthesis and RNA splicing. In the case of PUS10, researchers found that its ability to regulate viral elements is independent of its traditional enzymatic function.

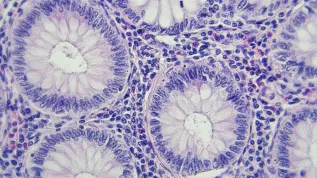

The team linked abnormal PUS10 activity to autoimmune disorders, including lupus—a disease often marked by a butterfly-shaped rash on the face—and non-specific colitis, a condition associated with Crohn’s disease.

“To further investigate the role of PUS10 in non-specific colitis in vivo, we compared the susceptibility to colitis (induced by a certain compound – DSS) in wild-type and PUS10-deficient mice. The results show that the lack of PUS10 leads to increased inflammation, while in wild-type mice, such symptoms were minimal,” Madej explained.

She added: “This indicates that PUS10 plays a significant role in regulating the inflammatory response in the intestine.” Chronic intestinal inflammation, as seen in inflammatory bowel diseases, is also a risk factor for colorectal cancer, underscoring the clinical importance of the findings.

Researchers also examined which genes were dysregulated in the absence of functioning PUS10. They found that the genetic signature was similar to that observed in patients with lupus, suggesting a role for the enzyme in the disease's development.

“The role of the PUS10 enzyme, which we described, can be compared to that of a sentinel, protecting cells from viral echoes from the past,” said Madej.

Although these ancient viral sequences are technically part of our genome, their abnormal activation mimics viral infection, leading the immune system to misidentify normal cells as threats.

This process may trigger autoimmune reactions, a mechanism previously proposed in scientific literature but now further clarified by the new findings. (PAP)

PAP - Science in Poland, Ludwika Tomala

lt/ bar/ jpn/