Wild mice are capable of creative thinking. There are many indications that they are capable of intentional deception to avoid an encounter with another individual, researchers have observed. This is the first time such high cognitive abilities have been described in murine animals.

Researchers from the Institute of Psychology at the Polish Academy of Sciences, the University of Warsaw, the IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute (Italy) and the Centre for Urban Ecological Solutions (USA) described the results of their work in the journal Royal Society Open Science. They documented for the first time a defensive behaviour in the field mouse: deceptive dodging during pursuit. The discovery was made while studying the behaviour of striped field mice and yellow-necked mice, which naturally inhabit similar areas and compete for food and habitats.

CROUCHING RODENT

A video showing an example of clever mouse behaviour. Source: Rafał Stryjek and team

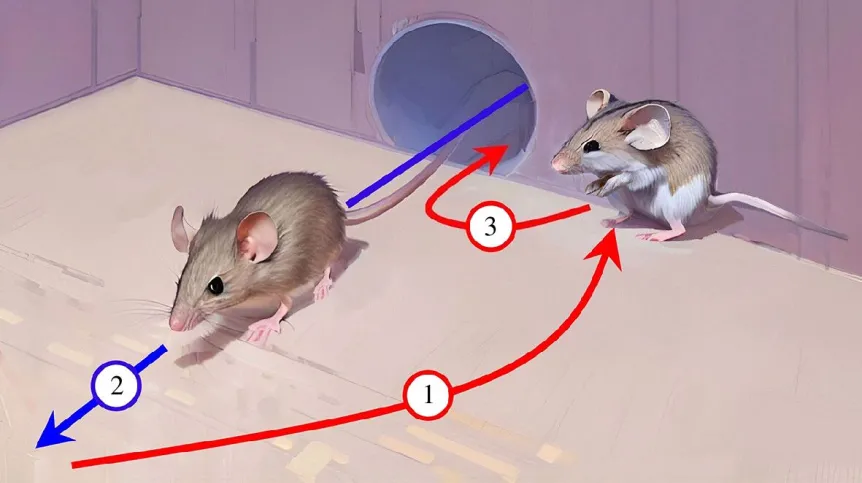

The striped field mouse was in a chamber with only one exit - a narrow corridor. When it heard that an intruder - usually a yellow-necked mouse - was approaching through the corridor, wanting to avoid a confrontation, the striped field mouse hid on the side of the chamber, right at the mouth of the corridor. The second mouse ran into the chamber and needed a moment to slow down and find its bearings in the new space, and then it passed the crouching one that was escaping. And the striped field mouse, taking advantage of its opponent's momentum and disorientation, slipped out through the corridor, gaining a lot of time to escape. Similar avoidance tactics were observed when a mouse fled down a corridor from a yellow-necked mouse. The escaping mouse quickly hid on the side, right at the mouth of the tunnel, and slipped out when the other mouse entered the chamber. This was not a one-off observation - similar creative behaviour was also observed in several other individuals.

Similar evasive behaviour in humans (here in a movie from the 1980s) can be considered intentional and clever.

ACCIDENT OF RESEARCH

The scientists investigated a completely different issue - the reactions of wild rodents to the natural scents of predators (e.g. foxes). For a total of seven months, they recorded videos of social interactions inside and around chambers placed in a natural environment (in forest and fields of Białołęka, Warsaw). They noticed the mice's clever escape behaviour while analysing the collected video materials.

'We cannot predict and simulate everything in laboratory conditions, which may limit our thinking to a small fragment of reality. To find answers to many questions, we need a more natural context and free-living animals that struggle with environmental challenges. It is for this purpose that we decided to study rodents in natural conditions', says Professor Rafał Stryjek, co-author of the study.

NOT ALL DECEPTIONS ARE THE SAME

According to the publication, the so-called behavioural deception is behaviour that allows an animal to gain something by providing false information to (or concealing true information from) another animal. However, most deceptive behaviour in animals is instinctive and therefore genetically programmed. This is the case, for example, when a mouse spots a fox or a bird of prey hunting it and freezes. It then becomes more difficult to detect and waits until the predator loses sight of it or is no longer interested in it. Or in the case of courtship, when, for example, male birds-of-paradise try to stun their partner with an unusual dance.

During courtship, birds also use the mechanism of deception, but - as scientists believe - this behaviour is not a result of creativity, but has genetic determinants instead.

However, some animals use deception in a flexible way, depending on the situation around them. This is called tactical deception. 'Tactical deception, requiring higher cognitive prerequisites, is rare and has been reported primarily in primates. Within tactical deception, the highest level is intentional tactical deception', the scientists say.

A voluntary tactic is employed to obtain an advantage over another animal in a way that is intentionally deceptive.

'This is the first report of a behavioural deception suggestive of intentional tactical deception in mice. Deceptive dodging appears to rely not merely on instinct or on learning, but rather on creative behaviour', say the scientists.

Stryjek adds that the observations require confirmation in further research.

'I sincerely hope that the results of our research will contribute to the promotion of non-invasive research techniques that favour animal welfare. If as a society - and this can be a problem - we realise how animals are intelligent, capable of feeling a wide range of emotions and suffering (not only the dogs and cats we love, and the primates we admire), maybe animals will have a better life with us’, he says.

The authors of the publication are Dr. Raffaele d'Isa from the IRCCS San Raffaele Scientific Institute in Italy, Michael H. Parsons from the Centre for Urban Ecological Solutions in the USA, Professor Piotr Bębas and Dr. Marcin Chrzanowski from the Faculty of Biology, University of Warsaw and Professor Rafał Stryjek from the Institute of Psychology of the Polish Academy of Sciences.

'So far, our research has not required very high financial outlays and we can carry it out thanks to funds granted to us by the University of Warsaw as part of the so-called IDUBs - small grants for promising basic research under the Excellence Initiative - Research University programme', the scientist says. (PAP)

PAP - Science in Poland, Ludwika Tomala

lt/ bar/ kap/

tr. RL