To maintain control over a huge area, the Incas used not only military force, but also religious elements. Rituals such as the capacocha are the manifestations of Inca dominance, and ceramic vessels accompanying the rituals are symbols of imperialism, says Dr. Sylwia Siemianowska from the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology at the Polish Academy of Sciences.

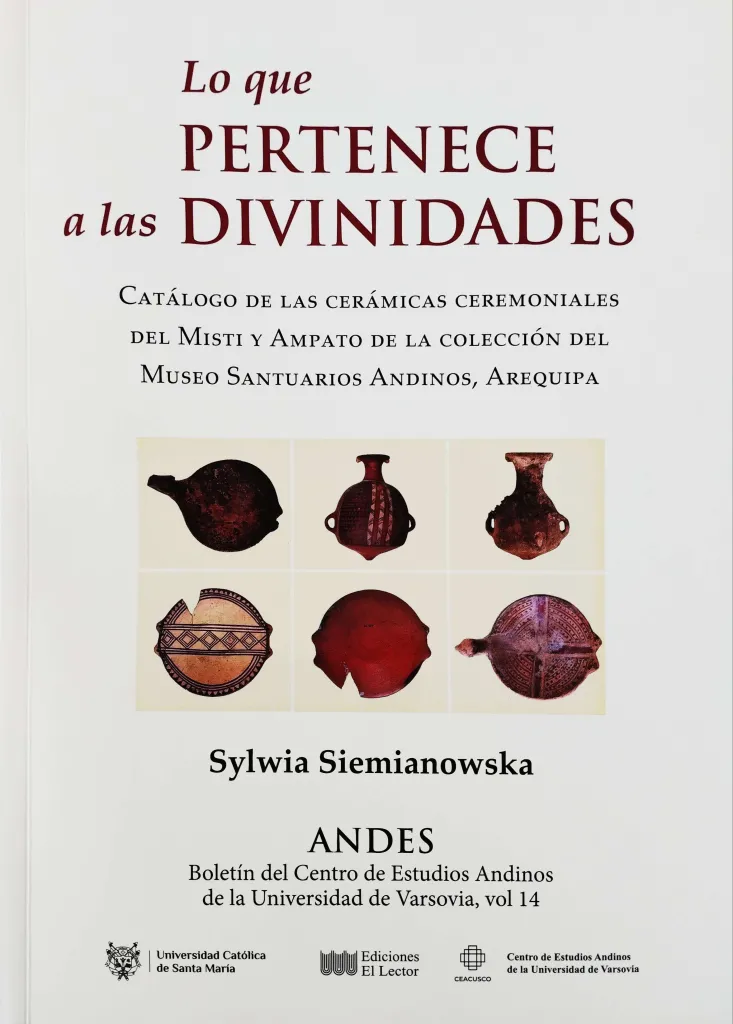

Dr. Siemianowska is the author of a recently published book devoted to ceramics that accompanied children sacrificed in the Inca capacocha ritual on the peaks of two volcanoes - Misti and Ampato. The bilingual (Spanish-English) catalogue Lo que pertenece a las divinidades/What belongs to the divinities contains detailed descriptions, photographs and drawings of the largest collection of Inca ceramics discovered in ritual contexts.

About 500 years ago, on the tops of mountains or volcanoes, the Incas sacrificed children as part of the capacocha ritual. In the area of Peru, Chile, Argentina and Ecuador, archaeologists already know of a dozen or so places where this custom was cultivated. The most famous ones include the peaks of the Ampato and Misti volcanoes in southern Peru.

'Children sacrificed during the capacocha ceremony were messengers to the gods. They brought them offerings and requests from people, and at the same time they were sacrificial offerings themselves', says Dr. Siemianowska.

Capacocha: ceramics as an enrichment of child sacrifice

Along with child sacrifices, various ceramic vessels were also offered as part of the ritual. Research from 2020, conducted by researchers including Dagmara Socha from the Centre for Andean Studies at the University of Warsaw, showed that eight or nine children aged six to 13 sacrificed on the Misti peak were accompanied by 47 figurines made of gold, silver, copper, wooden vessels, stone, bone and Spondylus shell artifacts, and 32 ceramic vessels.

In turn, three graves were discovered in Ampato, in which the remains of an approximately six-year-old boy and two girls (approximately six and 10 years old) were identified. They were accompanied by numerous grave goods, including 37 ceramic vessels. Together with the vessels found in the Misti burials, they are in the collection of the Peruvian Museo Santuarios Andinos in Arequipa.

'On the one hand, ceramic vessels are part of grave equipment, used to enrich the sacrifice itself. On the other hand, these vessels most likely also contained food products, either in liquid form, for example in the form of chicha (an alcoholic drink - ed. PAP), or in the form of solid food. Unfortunately, the climatic conditions in Misti and Ampato did not allow anything to be preserved inside', says Dr. Siemianowska.

In the Inca Empire, ceramic vessels were commonly used to honour the dead, place gifts for the deceased in them, feed and water the mummies of ancestors, deities, make ritual toasts, etc. They were also offered as gifts to huacas, or places of spiritual value. Ceramics played an important role in every Inca ritual.

Jugs and saucers and Inca imperialism

'This empire was the largest political unit in pre-Columbian South America. In order to keep their territory under control, the Incas developed a complex system that included not only military occupation and conquest, but also economic, political and ideological factors. Capacocha, like other rituals, was therefore one of the manifestations of Inca religious domination, and the ceramic vessels accompanying children during capacocha were symbols of Inca imperialism, manifested in everyday objects', Siemianowska says.

She adds that as everyday objects, ceramic vessels were carriers of ideas, symbols of belonging to a specific social group, determinants of norms and customs. Therefore, they had to have specific shapes, sizes, ornaments and quality

Vessels in all parts of the Inca empire always took on a specific form and decoration, which depended on the purpose of a given object. Vessels found in graves include plates, jugs, pots and bowls of various sizes - both shallow and deeper ones, with a handle or an application in the shape of a head, for example a bird head.

In the case of ceramics from Misti and Ampato, simple decorations dominate, presenting geometric figures, wavy, zigzag lines, arranged in various patterns. They were made with mineral paints after firing.

A chicha cup for a deity

An important element of all Inca rituals was the use of pairs of vessels. Archaeological analysis of ceramics found on the Misti and Ampato peaks has shown that pairs of puccu plates (a type of flat bowl or plate, usually small in size), bowls and Inca aryballos (a type of amphora used to store, transport or serve liquids or loose foods) are very common in capacocha contexts. The latter usually contained ceremonial chicha in Inca ritual contexts.

'It is a kind of gift to the deity. This can be seen, for example, during the sun ceremony described in historical sources, when the Inca held two cups in his hands. He drank chicha from one, and offered it to the Sun from the other cup. One cup was for him, the other was for the deity', says Dr. Siemianowska.

Vessels used during important religious ceremonies were most likely made specifically for this purpose. This was especially visible in the case of pots on a high leg, the walls of which were also very thin. In addition, all the miniature vessels did not have a purely kitchen function. It is assumed that they were made specifically as a funeral offering, which was to be used in the afterlife.

Five broken vessels were discovered in one of the Ampato graves. Based on the size of their fragments and their dispersion in the grave, researchers believe that they were deliberately destroyed to ritually close the sacred space. Most of them were made of a material that would not be suitable for kitchen use, which also indicates that they were fired with a ritual function in mind.

Other small but well-sealed vessels were used to make a so-called substitute offering. 'For example, llama blood was mixed with powdered Spondylus shell and such vessels were thrown towards volcanoes to make a sacrifice. Since we cannot reach the centre of the volcano directly, we make a symbolic offering through a vessel filled with gifts', Siemianowska says.

The publication Lo que pertenece a las divinidades was created as a result of many years of cooperation between the Centre for Andean Studies of the University of Warsaw and the Universidad Católica de Santa Maria in Arequipa, in which Dr. Siemianowska participates as an employee of the Institute of Archaeology and Ethnology. (PAP)

PAP - Science in Poland, Ewelina Krajczyńska-Wujec

ekr/ bar/ lm/ kap/

tr. RL

Gallery (10 images)

-

1/10Ampato, tomb 1, (5,800 m above sea level). Five broken vessels were discovered in the upper level of the first tomb. Credit: Johan Reinhard, archive of the Andean Sanctuaries Museum (Museo Santuarios Andinos UCSM) in Arequipa.

1/10Ampato, tomb 1, (5,800 m above sea level). Five broken vessels were discovered in the upper level of the first tomb. Credit: Johan Reinhard, archive of the Andean Sanctuaries Museum (Museo Santuarios Andinos UCSM) in Arequipa. -

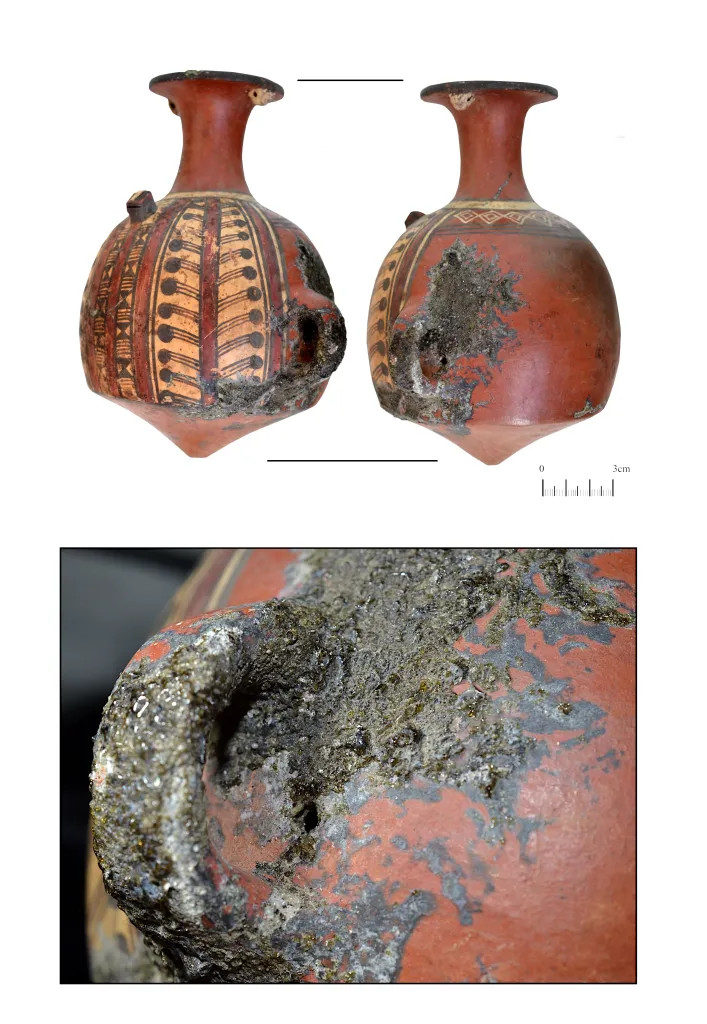

2/10Ampato, tomb 2, Inca aryballos with a partially glazed surface and a clear trace of a lightning strike. Collections of the Museo Santuarios Andinos (MUSA UCSM), inventory no.: UCSM00017MUSA. Credit: S. Siemianowska.

2/10Ampato, tomb 2, Inca aryballos with a partially glazed surface and a clear trace of a lightning strike. Collections of the Museo Santuarios Andinos (MUSA UCSM), inventory no.: UCSM00017MUSA. Credit: S. Siemianowska. -

3/10Ampato, tomb 1. a. an Inca aryballo, to this day tightly sealed with a cork made of clay mixed with organic material; b. an Inca aryballo with an additional perforated spout placed in the lower part of the base of the vessel. Collections of the Museo Santuarios Andinos (MUSA UCSM). Credit: S. Siemianowska.

3/10Ampato, tomb 1. a. an Inca aryballo, to this day tightly sealed with a cork made of clay mixed with organic material; b. an Inca aryballo with an additional perforated spout placed in the lower part of the base of the vessel. Collections of the Museo Santuarios Andinos (MUSA UCSM). Credit: S. Siemianowska. -

4/10Ampato, tomb 1, an Inca pot on a high leg. They were usually used for cooking, preparing meals, to transport food; they also served as one of the typical elements of equipping the deceased for the afterlife. Collections of the Museo Santuarios Andinos (MUSA UCSM). Credit: S. Siemianowska.

4/10Ampato, tomb 1, an Inca pot on a high leg. They were usually used for cooking, preparing meals, to transport food; they also served as one of the typical elements of equipping the deceased for the afterlife. Collections of the Museo Santuarios Andinos (MUSA UCSM). Credit: S. Siemianowska. -

5/10Misti, tomb 2. A miniature Inca pot on a high leg. On the bottom surface, a negative of fabric made of plant fibre is visible. Collections of the Museo Santuarios Andinos (MUSA UCSM). Credit: S. Siemianowska.

5/10Misti, tomb 2. A miniature Inca pot on a high leg. On the bottom surface, a negative of fabric made of plant fibre is visible. Collections of the Museo Santuarios Andinos (MUSA UCSM). Credit: S. Siemianowska. -

6/10Misti, tomb 2. Close-up of the outer part of the bottom of a miniature vessel with visible remains of organic substances, probably a fragment of a basket or pouch made of plant fibre, e.g. ichu grass. Collections of the Museo Santuarios Andinos (MUSA UCSM). Credit: S. Siemianowska.

6/10Misti, tomb 2. Close-up of the outer part of the bottom of a miniature vessel with visible remains of organic substances, probably a fragment of a basket or pouch made of plant fibre, e.g. ichu grass. Collections of the Museo Santuarios Andinos (MUSA UCSM). Credit: S. Siemianowska. -

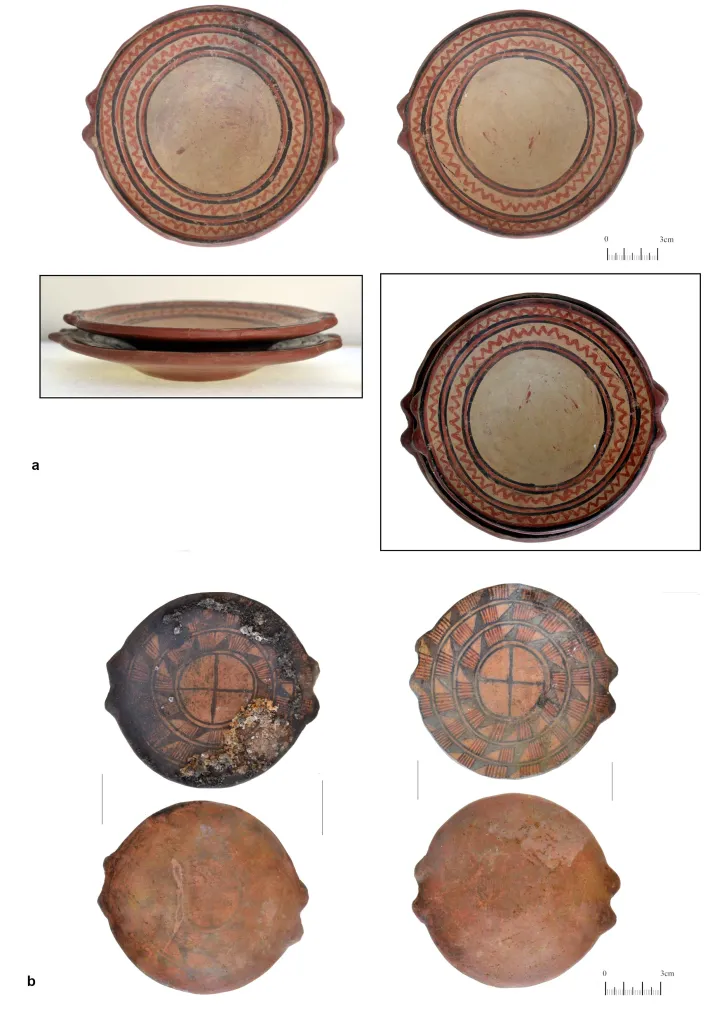

7/10Two pairs of Inca ppucu plates, which could occur in a wide range of shapes and decorations and can be monochromatic or polychrome. Collections of the Museo Santuarios Andinos (MUSA UCSM). Credit: S. Siemianowska.

7/10Two pairs of Inca ppucu plates, which could occur in a wide range of shapes and decorations and can be monochromatic or polychrome. Collections of the Museo Santuarios Andinos (MUSA UCSM). Credit: S. Siemianowska. -

8/10Misti, tomb 2, a miniature aisana puchuela vessel. Due to their size, they are treated as votive objects. Collections of the Museo Santuarios Andinos (MUSA UCSM). Credit: S. Siemianowska.

8/10Misti, tomb 2, a miniature aisana puchuela vessel. Due to their size, they are treated as votive objects. Collections of the Museo Santuarios Andinos (MUSA UCSM). Credit: S. Siemianowska. -

9/10Misti, various traces of mineral and organic substances visible on the surfaces of the analysed miniature vessels. Collections of the Museo Santuarios Andinos (MUSA UCSM). Credit: S. Siemianowska.

9/10Misti, various traces of mineral and organic substances visible on the surfaces of the analysed miniature vessels. Collections of the Museo Santuarios Andinos (MUSA UCSM). Credit: S. Siemianowska. -

10/10The cover of the latest publication summarizing the current state of knowledge about the ceramics accompanying the capacocha offerings from Misti and Ampato in southern Peru.

10/10The cover of the latest publication summarizing the current state of knowledge about the ceramics accompanying the capacocha offerings from Misti and Ampato in southern Peru.