Scientists have counted tardigrades living in Denmark. They recorded a four-fold increase in the number of species, including at least nine previously unknown ones. This was possible thanks to the help of hundreds of children who collected over 8,000 lichens and mosses, even from the most remote areas of Denmark.

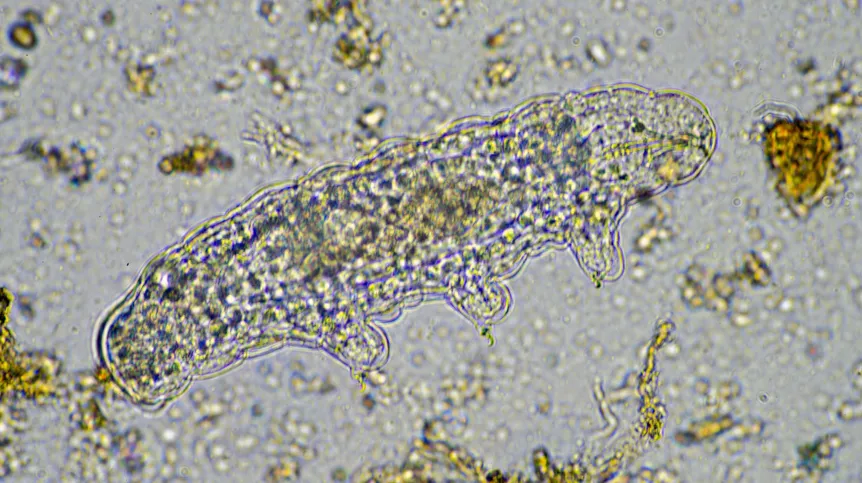

Tardigrades are microscopic relatives of arthropods, i.e. insects, arachnids and crustaceans. The largest ones very rarely grow to over 1 mm in length. They are important model organisms in studies of proteins that form the intracellular 'scaffold', and in the biology of ageing.

Due to the flourishing molecular methods used in the work of biologists dealing with biodiversity, the last decade has brought many papers devoted to the classification and distribution of tardigrades. However, this subject still requires further study, especially that a large part of historical works on the morphology and biogeography of tardigrades is outdated and inadequate in relation to the considerable species richness of these organisms.

To update the knowledge about tardigrades, a Polish-Danish team of researchers has just mapped tardigrade fauna in Denmark. A paper on this subject, co-authored by Dr. Piotr Gąsiorek from the Department of Invertebrate Evolution at the Faculty of Biology of the Jagiellonian University, was published in the journal Frontiers in Zoology.

Copenhagen to Jutland: tardigrades mapped

Thanks to the work of researchers, there has been a large increase in the number of known tardigrade species occurring in Denmark (almost fourfold, from 14 to 55, at least nine of which were previously unknown to science).

'The key parameter influencing the number of tardigrade species inhabiting a given area is the altitude above sea level. Mountains and upland areas have richer fauna species. Hence, Denmark, as a very lowland country with fairly uniform nature, strongly transformed by humans in the course of agricultural work and urbanization, has relatively few species. Fifty-five of them were detected, but only mosses and lichens were studied. If freshwater and soil environments were included, this number would increase by another few dozen species, but it would most likely not exceed 100', says Dr. Gąsiorek, who, as the only tardigrade expert in the team, was involved in sample analysis, DNA sequencing and species identification.

Children and mosses

During data collection, the scientists used the help of volunteer gatherers of mosses and lichens, recruited from among primary school students from different parts of Denmark. The joint efforts of hundreds of children resulted in collecting more than 8,000 fragments of lichen thallus and moss cushions, even from the remote and poorly accessible parts of Denmark. This allowed the researchers to select 700 samples representative for the available material

As part of the Masse Experiment project (https://masseeksperiment.dk/tidligere-eksperimenter/masseeksperiment-2023-mikroliv/), the children were provided with a special guide containing the basic principles of collecting mosses and lichens, which were to be examined for the presence of microscopic animals, especially tardigrades. In addition, the nature teachers conducted an introductory workshop with them based on the instructions provided by the research team. This enabled the children to collect suitably dried material in sufficient quantities.

'Each school collected five samples in cemeteries and city parks, and another five samples in an area relatively untouched by humans (e.g. a nearby forest complex). Schools from all over the country collected the samples over a period of about 1.5 months in the spring of 2023', Gąsiorek says.

An army of hundreds of little helpers

He adds that the campaign significantly increased children's awareness of tardigrades, mites, crustaceans, e.g. copepods and ostracods, mosses and lichens. During and immediately after the collections, the children had special classes devoted to these microscopic organisms. They saw many of these animals for the first time in their lives, which contributed especially to raising public awareness of elements of the ecosystem invisible to the naked eye.

'In practical terms, the help of hundreds of helpers has fundamentally sped up the process of obtaining biological material for scientific work. A team of 2-3 people would have spent much more time collecting material in often hard-to-reach areas of Denmark, as this island country has over 400 islands’, Gąsiorek says.

Biological 'tag' of the tardigrade

The main goal of the research - as the scientist explains - was to create a solid list of tardigrade species in Denmark, which would be supported by genetic data, i.e. the so-called biological 'tag' (DNA barcode), i.e. a very short fragment of the genome specific to the species. These fragments enable more certain identification of species, at least some of which are still unknown.

'Thanks to this, in the future it will be much easier to compare tardigrade species found by other scientists, e.g. during ecological studies. This approach significantly increases repeatability and comparability, which are key elements of reliable research', says Gąsiorek.

How are the 'Polish tardigrades' doing?

The tardigrade fauna of Poland has been systematically studied for a much longer time than the fauna of Denmark. According to the researcher, it is currently difficult to provide a precise number of Polish tardigrade species, because their taxonomy has been undergoing constant changes over the last decade.

'Many species previously considered to be present in our country are currently distinguished complexes of very similar but different species; others, in turn, have been deemed invalid and should be removed from the list of Polish tardigrades. One thing is certain: the Polish fauna has over 100 confirmed species, and their actual number is significantly higher, possibly around 150-200 species. This is the result of having mountains in the south, which hide many endemics', adds Gąsiorek.

In his opinion, mapping the tardigrade fauna of Poland is a much larger undertaking than the Danish research due to the size of the country, but it is worth considering using both microscopy methods and environmental DNA sequencing (eDNA).

Tardigrades have long remained very poorly known even among zoologists. They have four pairs of legs, but, unlike arthropods, their legs are jointless and can be pulled into the body thanks to their 'telescopic' structure. They have gained considerable popularity due to their ability to enter a state of latent life, cryptobiosis.

The most common type is anhydrobiosis, or the ability to survive in the event of almost complete dehydration of the body. It is very important for terrestrial tardigrades, which inhabit mosses, lichens, soil and forest litter - environments that are exposed to rapid drying. The molecular mechanisms of tardigrade anhydrobiosis are being intensively studied in view of potential applications, e.g. in medicine.

PAP - Science in Poland, Ewelina Krajczyńska-Wujec

ekr/ agt/ kap

tr. RL