The condition of forests and peatlands within them is strongly interconnected. Studies have shown that pine plantations operated in the Tuchola Forest since the 18th century have led to the weakening and acidification of the local peatland. This, in turn, weakens the resistance of the pines to climate change.

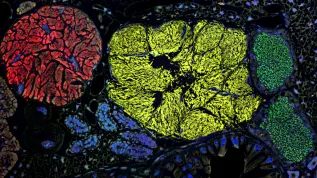

To investigate the relationships between forests and peatlands, scientists from the Climate Change Ecology Research Unit of the Faculty of Geographical and Geological Sciences at Adam Mickiewicz University collected data from various sources: they analysed historical records, maps from different periods, performed aerial measurements, analysed the composition of cores taken from the peat bog, studied tree growth in different periods and the relationships between air temperature and precipitation in a given year and the growth of tree rings.

'We need to think of the ecosystem as a system of interconnected vessels. If forests are in better condition, peatlands will be healthier. And if peatlands are in better condition, forests will be better off', says Mariusz Bąk, a doctoral candidate at Adam Mickiewicz University and the first author of the paper in Biogeosciences.

PINES ARE DOING WORSE

It could seem that pines were the only trees that were able to grow on the sandy soils of the Tuchola Forest, and that coniferous forests had been there for thousands of years. The truth is different, however: before humans began to manage it, the Tuchola Forest was covered with mixed forests, in which hornbeams, oaks and hazel also grew in addition to pines. At the end of the 18th century, Prussia decided to start forest management there and introduced pine plantations. For the last quarter of a millennium, coniferous trees have constituted a monoculture there - because of humans. It is one of the largest and longest-used managed forests in Poland. In addition, the trees growing there are mostly of the same age.

'We have shown that the current condition of the pine in the Tuchola Forest is not good. Although the pines from the Tuchola Forest show a similar reaction of growth rings to the climate as the pines from other parts of northern Poland, their sensitivity to the climate is higher', the researcher says. He explains that the main problem are the changes in the distribution of precipitation during the year. Increasingly frequent droughts in June and July weaken the pines, negatively affecting their condition and growth.

'Dendroclimatic models indicate that the optimal climate conditions for pine will change significantly in the next few decades, and its range will shift north. These forests will be under very high pressure related to water deficit, which will result in greater exposure to various types of disturbances such as fires, strong winds or pest outbreaks', warns Mariusz Bąk.

THE FOREST CHANGED THE PEATLAND TO FIT IT

Since it was known that the forest was doing worse, researchers decided to check how the peatlands located in its vicinity were coping. They analysed the history and condition of the Jezierzba peatland, a nature reserve since December 2024.

'Just as the condition of single-species and even-aged forests in the Tuchola Forest is poor, so is the condition of the local peatlands at the moment', the scientist says.

It turns out that the appearance of pine plantations at the end of the 18th century quickly changed the peatland. Before that, it was a low peat bog, resembling a shallow lake. It was overgrown with sedges, and fresh water was supplied by both groundwater and precipitation.

Following the introduction of intensive forest management, over several decades - also due to the presence of pine needles - the peatland acidified and became a raised bog. This means that it was dominated by peat mosses, which, among other things, gradually cut off the peat bog from the supply of groundwater.

He adds that remote sensing studies carried out in July showed that the surface of the peat bog could heat up to 45 degrees Celsius, which is a lot. This translates into poor condition of the plants, i.e. low amount of biomass.

'Peatlands are already under huge climatic pressure. They are called ticking carbon bombs because they contain huge amounts of carbon, and as groundwater levels drop, this carbon is released into the atmosphere', says Mariusz Bąk.

In his opinion, we still underestimate the role of peatlands in nature. 'We treat them as wastelands. Meanwhile, their role in the ecosystem is enormous: they store carbon and withdraw it from the so-called fast carbon cycle, and thus cool our planet. In addition, peatlands have the potential for natural retention - on a global scale, they accumulate 10 percent of freshwater resources', he emphasises.

WHAT CAN WE DO?

Scientists emphasise that this spiral of ecosystem quality degradation can be stopped by introducing diverse species of trees and shrubs into managed forests – in the case of the Tuchola Forest, these would be hornbeam or hazel, which are natural for those areas. This could strengthen the natural resistance of forests.

Another issue is learning the specifics of individual peatlands: examining the accumulated carbon resources, estimating the thickness and type of peat, in order to prepare tailor-made principles for the protection of wetlands in the context of climate change.

It is also worth taking care of natural retention in the area, so that changes in the distribution of precipitation do not harm the forests.

'Monoculture forests have simplified ecosystem connections and are therefore very sensitive to various types of changes in the environment. On the other hand, weak forests also mean weak peatlands in their area. And we know that they have an important role in the ecosystem. They contain more than twice as much carbon as the entire biomass of the world's forests. From the point of view of climate change, it is very important to recognise the functioning of peatlands in changing ecosystems', Mariusz Bąk concludes.

The research was conducted as part of the Polish National Science Centre grant 'Tracking disturbances in forest plantations using high-resolution palaeoecology and dendrochronology'.

Science in Poland, Ludwika Tomala

lt/ agt/

Gallery (5 images)

-

1/5Core taken from the Jezierzba Peat Bog for palaeoecological research. Credit: Katarzyna Marcisz

1/5Core taken from the Jezierzba Peat Bog for palaeoecological research. Credit: Katarzyna Marcisz -

2/5Jezierzba peatland surrounded by a Scots pine plantation in the Tuchola Forest - the research object. Credit: Mariusz Lamentowicz

2/5Jezierzba peatland surrounded by a Scots pine plantation in the Tuchola Forest - the research object. Credit: Mariusz Lamentowicz -

3/5The red peat moss Sphagnum rubellum growing on Jezierzba peatland, a species typical for acidified peatlands. Credit: Mariusz Bąk

3/5The red peat moss Sphagnum rubellum growing on Jezierzba peatland, a species typical for acidified peatlands. Credit: Mariusz Bąk -

4/5Jezierzba peatland in the Tuchola Forest, subject to Scots pine succession. Credit: Mariusz Bąk

4/5Jezierzba peatland in the Tuchola Forest, subject to Scots pine succession. Credit: Mariusz Bąk -

5/5Mariusz Bąk collects cores from Scots pine in the Tuchola Forest. Credit: Mariusz Lamentowicz

5/5Mariusz Bąk collects cores from Scots pine in the Tuchola Forest. Credit: Mariusz Lamentowicz