A newly identified snake species from 37 million years ago is providing rare insight into the early evolution of caenophidians, the group that today dominates snake diversity worldwide, according to palaeontologists who described the fossil based on material from southern England.

The species, named Paradoxophidion richardoweni, was identified from fossil vertebrae recovered at Hordle Cliff on the southern coast of England and dates to the late Eocene.

The research was carried out by Georgios Georgalis, PhD, of the Institute of Systematics and Evolution of Animals of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Krakow, and Marc Jones, PhD, of the Natural History Museum in London.

Georgalis said the snake’s anatomy sets it apart from all previously known fossil and living species.

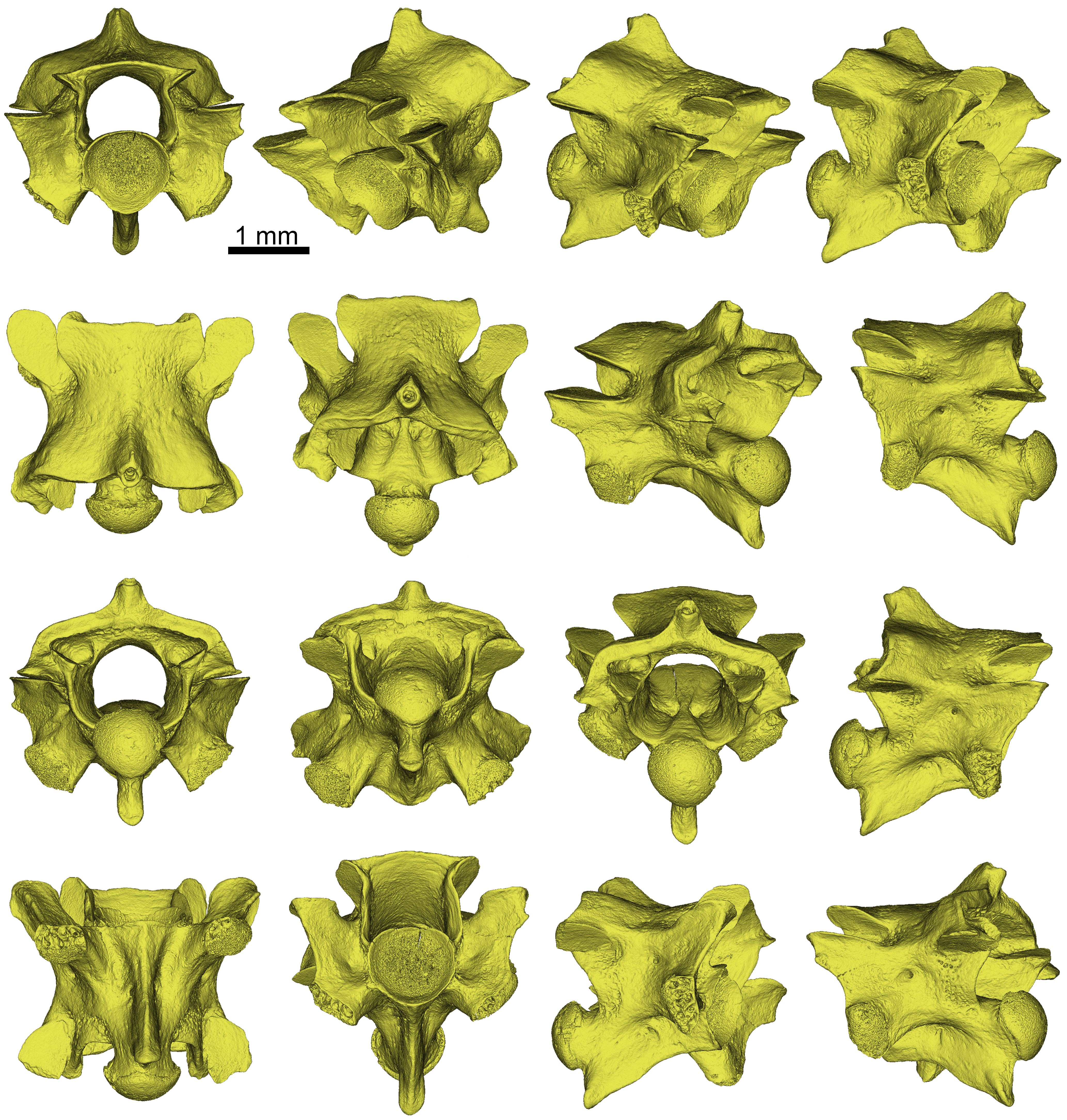

“The snake is ‘strange’ because this small snake (probably no longer than 1 metre) was characterized by vertebral morphology that doesn't match any other known snake. Instead, it resembles a mosaic of anatomical features found in very different groups of modern and fossil snakes,” he said.

The material consists of numerous vertebrae recovered from a single site, representing nearly all regions of the spine. This allowed the researchers to analyse anatomical variation along the vertebral column within a single individual.

“Furthermore, numerous fossil vertebrae (all found at a single site, Hordle Cliff in the UK) came from almost all sections of the spine, which enabled a proper assessment of so-called intracolumnar variation (i.e., significant differences in the structure of vertebrae within a single individual - different vertebrae occur in the anterior, middle, and posterior parts of the spine),” Georgalis said.

The fossils are part of the Natural History Museum’s collections and had not been examined in detail before. The researchers analysed them using micro-computed tomography (CT) scanning and comparative anatomical methods.

Those analyses showed that Paradoxophidion belongs to Caenophidia, a group that includes most living snake species.

“Caenophidia constitute the dominant group of snakes in the world today, comprising thousands of species found almost everywhere on Earth, including iconic and medically important forms such as cobras, vipers, rattlesnakes, mambas, and coral snakes. However, during the Eocene (56–34 million years ago), when Paradoxophidion lived, caenophidians were not common at all, on the contrary, the snake fauna of that time was dominated by boas, pythons, and other more ‘primitive’ snakes, inhabiting the vast tropical and subtropical forests of Europe (and other continents). In these Eocene ecosystems, caenophidians were rare, and only a few fossils of this group are known,” Georgalis said.

The study also identified similarities between Paradoxophidion and modern acrochordids, commonly known as elephant trunk snakes, which live in aquatic habitats in South Asia and northern Australia.

“Interestingly, several anatomical structures of the vertebrae of Paradoxophidion bear a striking resemblance to modern acrochordides. Acrochordide, known as ‘elephant trunk snakes’, are large aquatic snakes that inhabit rivers, estuaries, and mangroves of South Asia and northern Australia. Most recent phylogenetic studies indicate that acrochordides are the most ancestral members of the Caenophidian family. With such anatomical similarities, it is therefore possible that Paradoxophidion belongs to acrochordides, representing their oldest fossil record and extending their former range as far as England. In any case, it certainly holds the key to understanding the early evolution of the Caenophidians, being an early offshoot of this currently dominant group of snakes,” Georgalis said.

Georgalis said further research on museum collections is likely to reveal additional species.

The collection of Eocene snakes at the Natural History Museum in London, which he is studying, includes numerous previously undescribed fossils.

“I intend to uncover further interesting +surprises+ from this fascinating stage of snake evolution’,” he said.

The findings have been published in the journal Comptes Rendus Palevol. The research was supported by a grant from the Polish National Science Centre. (PAP)

PAP - Science in Poland

akp/ agt/

tr. RL