You encounter a bear in the woods. Do you flee breathless, or stand motionless, hoping that the bear will not notice you? The brain must choose a strategy to deal with the threat in a fraction of a second. Biologist Natalia Wróblewska talks about the scared brain research.

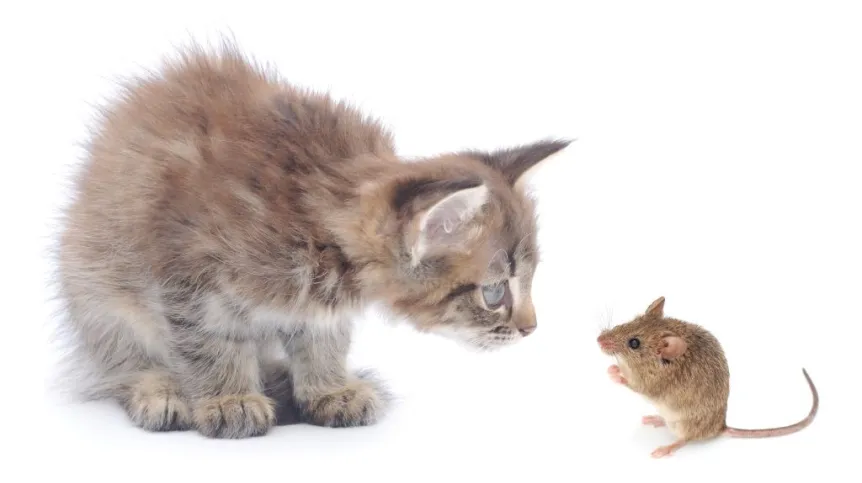

You\'re walking through the forest and, all of a sudden, a big bear jumps out onto the path. One thing is certain - you will feel fear. Your blood pressure will jump and your heart rate will increase. But what else? Some will immediately start to run, others will be "paralysed" by fear, not able to even twitch. "Similarly in mice. When a mouse sees a threat, it either starts to flee, or freezes. The latter strategy also makes sense: there is a chance that the predator will not notice the immobile mouse or think that it is a carcass, an uninteresting target of attack. It is one of the innate possibilities of reacting to danger" - says Natalia Wróblewska, who is doing her PhD at the University of Cambridge.

The Polish biologist works in the laboratory headed by Tiago Branco from UCL. She investigated how the brain makes a decision in such a crisis situation: escape or freeze. "It depends on many factors - how close the threat is, how far the hideout is, whether we\'ve had experience with dangerous animals, whether we are fast runners, whether we are tired and hungry... These decisions have to be processed in a fraction of a second. That\'s how quickly the brain makes the decision" - she says.

As part of fear research, the biologist investigates how mice respond to snake skin. A piece of skin shed by a snake - a moulting - is placed in the cage. "Although the mouse born in a lab has never seen a snake, when it smells the snake it feels fear and escapes into the burrow" - the scientist says. She explains that the strategy of freezing does not make sense - the threat is not in sight.

Researchers in various laboratories resort to various tricks to trigger fear in mice in controlled environments: a shadow of a predatory bird is moved over the cage, or a wet cloth, with which a cat has been wiped, is placed in the cage.

"When the mouse smells a predator, its neurons are activated sequentially in different regions: in the epithelium of the nose, in the amygdala of the brain, then in the hypothalamus - I focus on those in my research - then in the midbrain, and finally in the spinal cord. Those neurons are responsible for muscle activation. We are wondering how the information is processed at each of these stages" - says Natalia Wróblewska.

If information about the threat went straight from the nose to the muscles, the mouse would not have the chance to integrate important information. "If they are young nearby, the mouse will probably not run away, but will try to defend them instead. Its behaviour will change completely" - the researcher told PAP.

"I like to look at neurons as if they were calculators. They do specific mathematical tasks, they add, subtract information or even multiply it. I try to understand how cells process information they get, and how they help decide which behaviour is best in a given case" - says the biologist.

"We humans, although we may not be afraid of cats and birds, we still have a similar network of connections in the brain" - she says. Understanding how fear information works in mice brings us closer to understanding how it can work in a healthy person. And this knowledge will allow us to understand what happens in the brain that does not work properly - for example in mental illness.

According to Natalia Wróblewska, if we understand that, for example, the cells of the hypothalamus are associated with the sense of anxiety, we may be able to use this knowledge in the future. And, for example, develop a drug that will affect the activity of these cells and reduce the level of anxiety in people with anxiety disorders.

Author: Ludwika Tomala

PAP - Science in Poland

lt/ zan/ kap/

tr. RL