The domestication of wolves was common practice several thousand years ago, according to researchers.

Archaeologists have been discussing for years when wolves were domesticated and when they became a permanent part of human settlements.

Recently, based on the analysis of excavated wolf skull measurements among other things, researchers suggested that the first ancestors of dogs could have lived with people as early as 30,000 years ago.

But according to Kraków archaeozoologists Professors Jarosław Wilczyński and Piotr Wojtal from the Institute of Systematics and Evolution of Animals of the Polish Academy of Sciences, evidence of such early domestication of the wolf is far from sufficient and based on unconvincing premises. The hypothesis about dog domestication only a dozen or so thousand years ago is much more probable, they argue.

The researchers from the Polish Academy of Sciences point out that dog and wolf bones are very difficult to distinguish, which complicates archaeozoological research. Because there are practically no differences between the remains of both species, the context of the find and all traces left on it by humans and animals help to interpret the results.

One of the main arguments for early (about 30,000 years ago) domestication are the measurements of wolf skulls from Gravettian sites in southern Moravia, primarily from Předmostí.

Professors Jarosław Wilczyński says, however, that the remains of wolves from that site do not bear any traces that would support the hypothesis about their early domestication.

He told PAP: “Most of the remains belong to adult animals. Meanwhile, if the former inhabitants of the site actually kept dogs, we would certainly discover the remains of young animals in the camp, which would have been eliminated due to natural causes or as a result of intentional human action. There are no such remains in Gravettian sites.”

In addition to wolf bones, Polish archaeozoologists working at Moravian sites examined tens of thousands of remains of other species. Only individual bones were gnawed in a way that indicates a dog or wolf, which also lends support to the early domestication hypothesis.

Wilczyński said: “We know that dogs are often fed with leftovers +from the table+. Such a low share of bite-bearing remains proves that carnivores did not have access to animal carcasses accumulated in these sites.”

This activity of dogs is well known from settlements from several hundred years ago, in which hunters and gatherers lived, including Inuit settlements from the Arctic, where dogs played an important role in everyday life. The animals consumed up to 35 percent of supplies consisting of meat, soft tissues and bones.

“When excavations are carried out, for example within Neolithic settlements or medieval towns, we find numerous animal bones bearing traces of dog teeth. People were throwing away the leftovers that were eaten by their animals. We cannot see traces of a similar activity among the Moravian finds from almost 30,000 years ago,” Wilczyński said.

Colleague Professor Piotr Wojtal added: “We believe that the numerous remains of wolves in Moravian sites are evidence of the hunters' specialization rather than the early process of dog domestication.”

In other words, the remains of wolves discovered in the area of 30,000 years old settlements in today's Moravia belonged to animals killed in the vicinity of the settlement, and they do not constitute evidence of their domestication.

Wolves, like reindeer, horses and mammoths were probably treated as a source of skins and meat. This is supported by traces of cuts on wolf bones, made during skinning, cutting carcass and filleting.

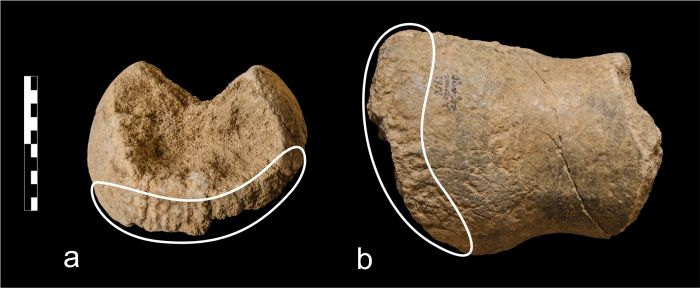

Mammoth bones bitten by wolves (marked) from the Pavlov I site. Credit: P. Wojtal

Researchers believe that the mass killing of wolves about 30,000 years ago in Moravia resulted from the need to eliminate the most important competitor for game resources and to protect human settlements from this predator.

The article on wolf domestication appeared in the Journal of Archaeological Anthropology (https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0278416520300015).

In addition to the two researchers from the Polish Academy of Sciences, its authors are Gary Haynes from the University of Nevada in Reno (USA), Łukasz Sobczyk from the Jagiellonian University, Jiří Svoboda from the Czech Academy of Sciences and Masaryk University, Martina Roblíčková from the Moravian Museum in Brno.

PAP - Science in Poland, Szymon Zdziebłowski

szz/ zan/ kap/

tr. RL