Corals are more complex organisms than some researchers have believed. These animals are able to regulate the formation of minerals from which their skeleton is formed, according to research led by Polish scientists, who discovered corals with an unusual skeleton structure. And this means that there is a chance that some of the corals will be able to cope with the increasing acidification of the oceans.

Corals build massive calcium carbonate skeletons. Consequently, they form the largest biological structures on Earth: reefs. A team of scientists led by Professor Jarosław Stolarski from the Institute of Paleobiology of the Polish Academy of Sciences has discovered that a certain species of contemporary coral from the Southern Ocean has a very unusual skeleton structure. This skeleton is made of two different types of calcium carbonate: not only aragonite, which is typical for corals, but also calcite, previously unseen in contemporary corals. The research results were published in PNAS: https://www.pnas.org/cgi/doi/10.1073/pnas.2013316117.

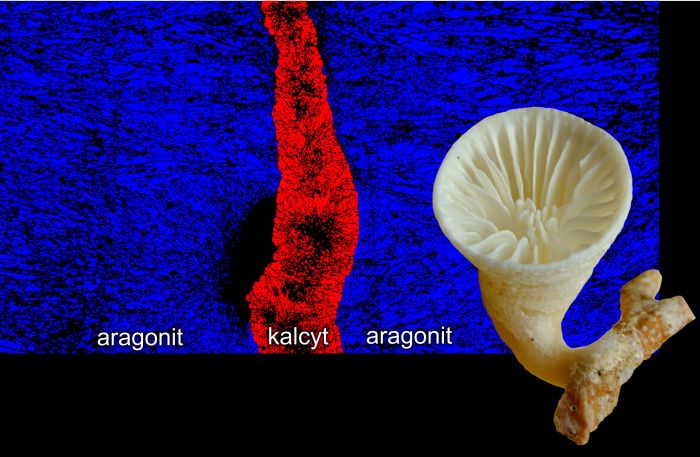

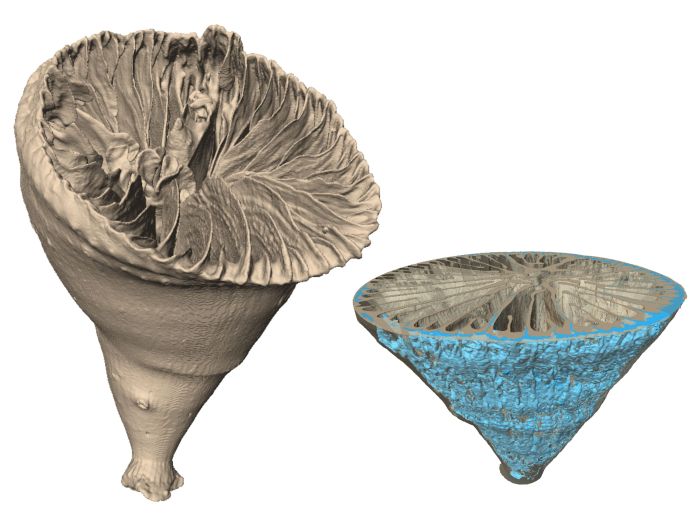

The deep-water solitary coral Paraconotrochus antarticus forms a skeleton made of two types of calcium carbonate: calcite and aragonite (marked with different colours on the skeleton cross-section). All other today's corals have aragonite skeletons, and to understand this difference, one must go to the deep evolutionary roots of this coral. [fig. Jarosław Stolarski]

Professor Stolarski told PAP that calcium carbonate is one of the most common chemical compounds on Earth: it is the main component of limestone rock, cave infiltrates, and the skeletons of most invertebrates, shells of snails, clams, etc. It occurs in many mineral forms, the most common of which are aragonite and calcite. With the present composition of the seas and oceans, aragonite, not calcite, is the form of calcium carbonate that precipitates naturally. For this reason, some scientists believed that the corals that form aragonite skeletons only minimally regulate the process of their formation. They simply form the skeleton built of the variety of calcium carbonate that is easiest to precipitate in the environment.

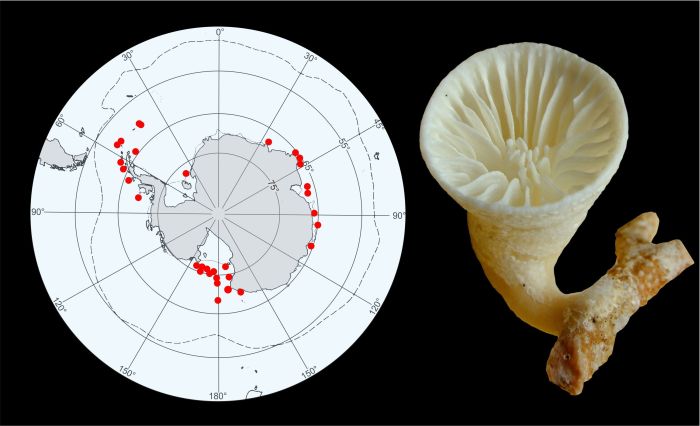

The deep-water solitary coral Paraconotrochus antarticus (right) forms a skeleton made of two types of calcium carbonate: calcite and aragonite (marked with different colours on the skeleton cross-section). [fig. Jarosław Stolarski]

But the conditions in the oceans are changing: their acidification is increasing due to the dissolution of carbon dioxide in water (and the formation of carbonic acid). This results in a real threat that coral skeletons would begin to dissolve on a large-scale.

The situation is different for more complex organisms such as molluscs. While they also form a calcium carbonate skeleton, they regulate its formation very precisely. For example, oysters make shells from two types of calcium carbonate: calcite (outer shell) and aragonite (inner shell, a component of mother of pearl). This means that the mineral, from which these organisms form their skeletons, depends mainly on physiology, not environmental conditions. Therefore, it can be concluded that in deteriorating environmental conditions, organisms that can actively regulate skeletal mineralisation will be able to resist ocean acidification more effectively, for example by changing the skeleton composition to be more resistant to dissolution. Molluscs appeared to be 'tougher' than corals.

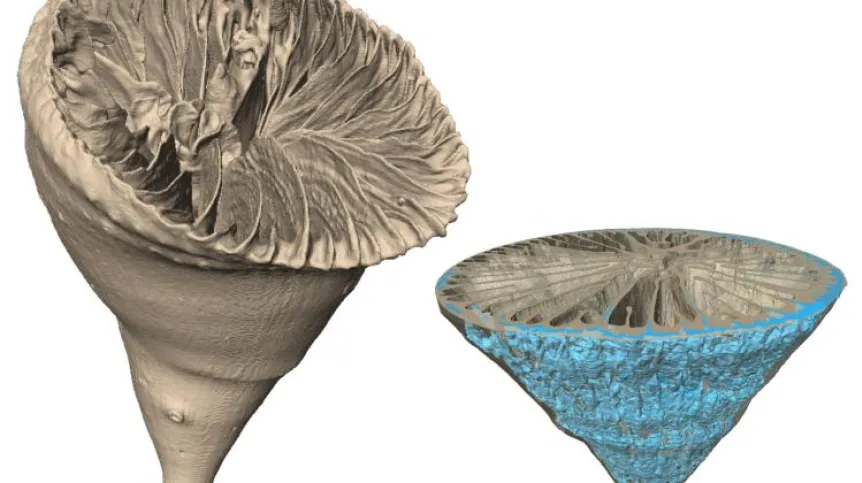

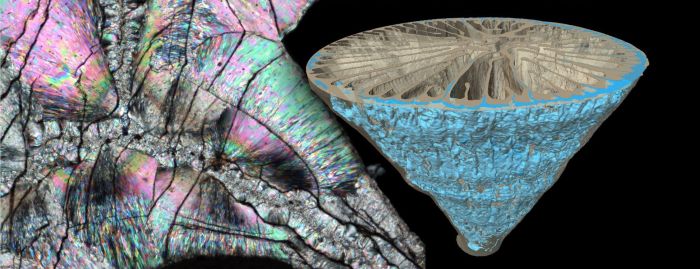

The deep-water solitary coral Paraconotrochus antarticus forms a skeleton made of two types of calcium carbonate: calcite and aragonite. Due to their different densities, these minerals can be imaged in a computed tomography (on the right the inner, calcite component of the skeleton is marked in blue). (fig. Katarzyna Janiszewska, Jarosław Stolarski)

For several years, palaeontologists have known about the case that constitutes a hole in this reasoning. A coral from around 100 million years ago, unlike all other corals, built its skeleton not of aragonite, but of another type of crystalline calcium carbonate - calcite. This fossil species was described in Science in 2007 by Polish researchers under the supervision of Professor Jarosław Stolarski. Now the same team of scientists has made another discovery.

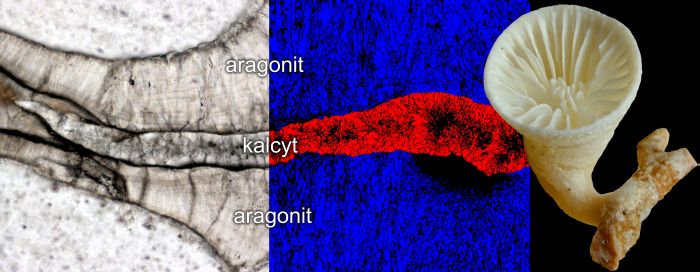

The solitary coral Paraconotrochus antarticus, which forms a unique skeleton made of two types of calcium carbonate (calcite and aragonite) is commonly found in the deep waters of the Southern Ocean. [fig. Jarosław Stolarski, Katarzyna Janiszewska]

“I noticed the similarity of one of the coral species from the Southern Ocean to this unusual fossil species that we described several years ago,” the scientist says. His intuition did not fail him. Although it turned out that the outer part of the skeleton of this contemporary coral was made of typical aragonite, the interior of the skeleton was made of calcite. This coral is therefore able to produce different minerals at the same time. This is an advanced skill. Moreover, it turned out that genetically the coral represents a very old line of corals that emerged at least 100 million years ago, possibly the same from which the calcite coral described earlier evolved.

He added: “We now know that corals do not just passively precipitate calcium carbonate from seawater. They control this process very precisely.” Hence the conclusion that corals are more complex than previously thought.

The deep-water solitary coral Paraconotrochus antarticus forms a skeleton made of two types of calcium carbonate: calcite and aragonite. Due to their different densities, these minerals can be imaged in a computed tomography (on the right the inner, calcite component of the skeleton is marked in blue). The thin plate of the skeleton in a polarizing microscope shimmers with all the colours of the rainbow, but there is also a visible border between the central calcite part and the outer aragonite part. [fig. Jarosław Stolarski, Katarzyna Janiszewska]

Stolarski said: “Thanks to this research, we can partially predict the future. If the environment changes so much that aragonite is no longer so easy to produce, for example as a result of the acidification we are now seeing, though many corals will certainly die out, some will still be able to actively produce it in the new conditions.

“So there is a chance that not all corals will disappear forever with global warming; some of them will probably adapt to the 'new' environmental conditions, which, from the geological perspective reaching millions of years into the past, are not so new.”

PAP - Science in Poland, Ludwika Tomala

lt/ agt/ kap/

tr. RL