Is it possible that the team working for almost 70 years on a historic atlas of 16th century Poland made such a huge, cardinal error? How did we lose a forest? These questions started the scientific search for the alleged forest that disappeared from the map of the border of old Polish districts of Poznań and Kościan.

Is it possible that the team working for almost 70 years on a historic atlas of 16th century Poland made such a huge, cardinal error? How did we lose a forest? These questions started the scientific search for the alleged forest that disappeared from the map of the border of old Polish districts of Poznań and Kościan.

Dr. Tomasz Związek talks about the detailed studies conducted in the Historical Atlas Department of the Institute of History of the Polish Academy of Sciences. He is a co-author of the paper recently published in the Journal of Historical Geography, describing the grassroots research project. Researchers analysed the process of forest cutting by Mennonite settlers in the late modern period. The paper is the result of several years of research on this subject and, among other things, illustrates the scale of anthropopressure, the impact of humans on the landscape.

PAP - Science in Poland: What does this mean that it is a grassroots research project? Is it because it is inspired by pure scientist curiosity? And how is such a project conceived?

Dr. Tomasz Związek: Some time in 2015-2016, during the preparation of another volume of the 'Historical Atlas of Poland. Detailed Maps, 16th Century' one of the researchers working at the Historical Atlas Department of the Institute of History PAS noticed an error on a map depicting settlement on the fragment of the border of two old Polish districts of Poznań and Kościan - there was no forest or any settlement structures. A quick view of the map caused great concern of team members. We were wondering if it was possible that the team working for almost 70 years on a historic atlas of 16th century Poland made such a huge, cardinal error? How did we 'lose a forest'? This problem became a starting point for detailed studies.

Such a big spot on the map was unnatural. We wanted to explain what had happened to the former forest.

SiP: Before you talk about 'deforestation', please tell us what the lost old Polish forest looked like.

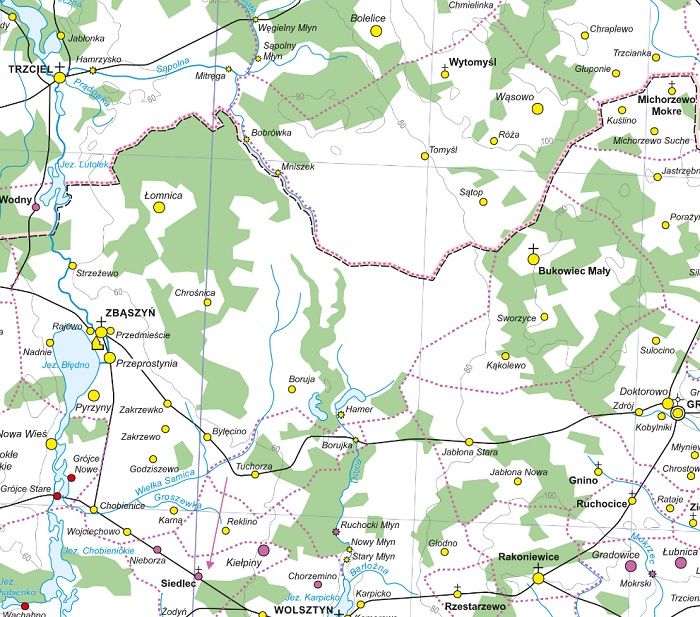

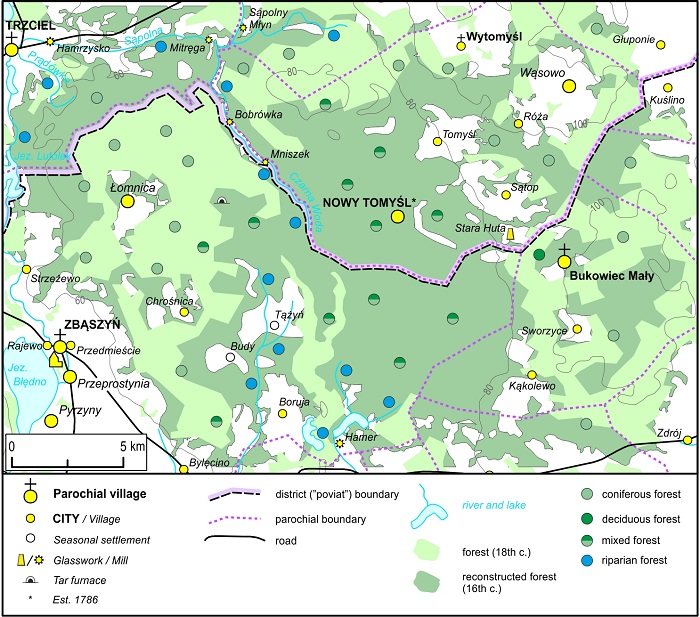

T.Z.: We gradually discovered the landscape, which only to a small degree overlapped with what we know from our own experience from the area of today's Nowy Tomyśl. Above all, according to the early modern period court books, it clearly a wooded area. From the north, it was cut with eskers forming sandy hills, the centre and the southern edge was covered with swampy forest.

Reports on inspections of border mounds, scattered densely in this area, which we found in the written sources, pointed to a large wealth of the local flora. We read about pines, hills covered with yew, oaks, beeches, birches, hornbeams and sycamore trees.

It was not a forest wilderness, however. There was normal human life on its outskirts, glass smelters were founded, there were tar kilns, forest clearances were used as pastures. The fact that it was a valuable forest complex is confirmed by records of altercations between the local nobility, who illegally cut the best trees.

SiP: The forest was not colonized in the Middle Ages. What saved it?

T.Z.: According to our observation, the reason is quite simple. The local residents lacked knowledge of the relevant drainage techniques. About 200-300 years had to pass before the issue of forest cutting in the vicinity of Tomyśl could be revisited. In the beginning of the 18th century, Polish economy had to bounce back after the crises of the Deluge, the North War. The lands of the Commonwealth also became a safe haven for migrants, also due to the emerging religious unrest in the west of Europe. At that time, there was an influx of Mennonites.

SiP: Mennonites are Protestants from the Dutch-speaking parts of Europe. Who were they? What brought them to Poland?

T.Z.: They were not a uniform group, defined by their ethnicity, but rather by the law according to which they lived. Their functioning in colonized areas was regulated on the basis of direct agreements (contracts) between new settlers and the owners of individual lands. In addition to strictly economic or confession issues, the privileges also regulated how the Mennonites could affect the surrounding nature. From these documents, we know which types of trees were to be protected from cutting (for example oaks), from which parts of forest settlers could freely cut the trees for their needs, and which could not touch under any circumstances.

SiP: Pioneering ecological regulations?

T.Z.: I think they did not have anything to do with ecology. Remember that in the pre-industrial age, nature has a very clear role. It fed, dressed, protected and finally heated. It was also simply a financial security for landowners. That's is how we explain why landowners from the Nowy Tomyśl area - the Szołdrskis - clearly stated in contracts with Mennonites that oaks could not be felled under any circumstances. Today, many of these trees the remember the times of melioration of today's Nowy Tomyśl Plain have reached the size of monument trees.

SiP: And what about the Dutch specialty, the construction of channels?

T.Z.: Mennonites were famous for bringing the skill of effective drainage of wetlands to the Polish lands. On the one hand, it allowed them to drain areas such as those that we know today from the area of Nowy Tomyśl. On the other hand, they adapted to life in places periodically flooded by flowing water. A good example are numerous settlements founded along the Vistula in the 18th and 19th century. Interestingly, in today's Nowy Tomyśl Plain, channels dug by Mennonites in the 18th and 19th century serve the local population to this day.

SiP: Who can use your research and what for?

T.Z.: While studying the history of the arrival of Mennonites, we wanted to not only show the scale and dynamics of processes related to deforestation and adaptation of the transformed landscape into farmland. We also pay attention to great environmental consequences of the processes that occurred in the past and their great importance for today's discussions related to progressive climate change.

We also want to show a direct relationship between the activity of our ancestors and problems faced by people in the beginning of the 21st century.

We were also interested (from a methodological point of view) in how we (as researchers) can restore these old landscapes. We wanted to set a standard in thinking about these problems and propose ideas and solutions to our colleagues from other countries.

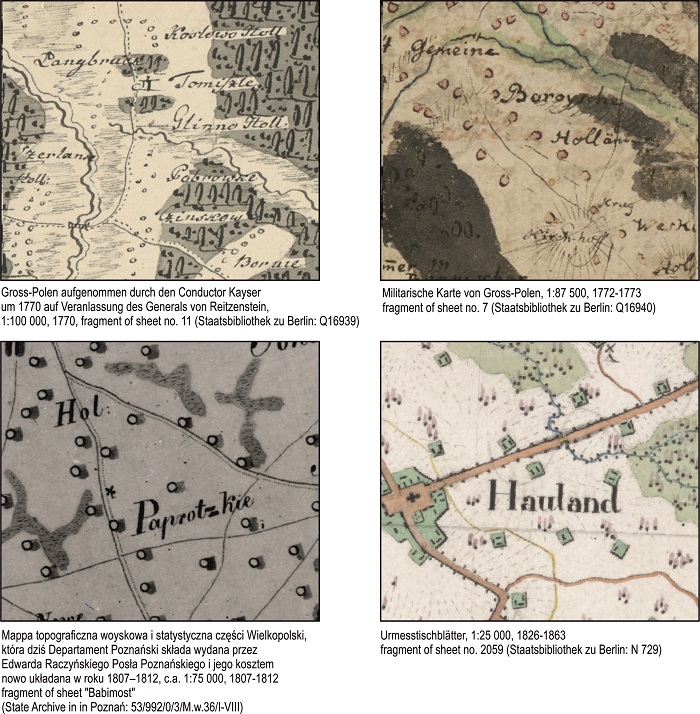

In the paper, we show how old (mainly 18th and 19th century) maps showed Mennonite settlements. We model various ways of land management by Mennonite settlers. Individual methods and stages of forest cutting and land draining were investigated based on written, cartographic and archaeological sources. We were interested not only in changes in the settlement structure, Mennonite contracts with landowners, we also carried out a linguistic (onomastic) analysis, drawing out the relics of the former landscape from the geographical names in this area.

This whole set of research processes and methods allows to better understand the past and prompts us to think about the direction in which we are going today. On me personally, it made the greatest impression when we travelled on bicycles during field research while looking at Prussian maps from the beginning of the 19th century. We clearly saw the scale of landscape transformations over the last 200-300 years. And believe me, the scale is huge.

The paper is available HERE.

PAP - Science in Poland, Karolina Duszczyk

kol/ zan/ kap/

tr. RL