Polish scientists have found that a species of moss (Syntrichia sarconeurum) has survived in Antarctica for at least two million years, making ‘a significant contribution to understanding the history of Antarctic biodiversity.’

Publishing their findings in the Journal of Biogeography (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1111/jbi.14476), the scientists from the Polish Academy of Sciences in Kraków say the discovery will help make predictions about how climate change will affect biodiversity.

Mosses are the main component of the Antarctic vegetation cover. It has long been known that they have a great physiological ability to survive the stress associated with low temperatures and dryness of the environment. Despite their delicate structures, they can remain alive for hundreds of years.

However, team leader Dr. Michał Ronikier from the Academy’s Institute of Botany told PAP that scientists “have been wondering how far their ability to survive in Antarctica extends, and above all on the Antarctic continent'. Currently, the area of ice-free Antarctic land areas is estimated at about 0.5 percent, and it was even smaller in the glacial period.

Roniker said: “Until recently, the hypothesis of the total extinction of the Antarctic biota (all organisms present in a geographical region at a certain time - PAP) during the historical glacial periods dominated, but research on invertebrates gave hope that even during the glacial peaks - when climatic conditions were at the extreme - certain organisms found refuges in which they survived the most difficult periods.”

In order to have a fresh look at the presence of mosses in Antarctica today and in the past, the scientists proposed combining classical research competences with modern genetic research - molecular biogeography. Work on plant samples collected in the herbarium of the Institute include dried moss specimens collected during scientific expeditions in the first half of the 20th century.

Roniker said: ”We owe it to Professor Ryszard Ochyra that the Institute of Botany of the Polish Academy of Sciences has one of the largest herbarium collections of Antarctic mosses in the world. For a long time, it was possible to use it for classical morphological analyses. Now that we have molecular biology at our disposal, the scope of use of such collections is significantly expanding and thus opens up fascinating perspectives. We are able to read the genetic material of dried mosses, degraded as a result of the passage of time, with increasing accuracy.

“Classical, taxonomic competences, often overlooked in molecular research, remain crucial for selecting the best model species for research and relying on verified, well-labelled materials. That is why cooperation and combining skills are so important. This is the strength of our project.”

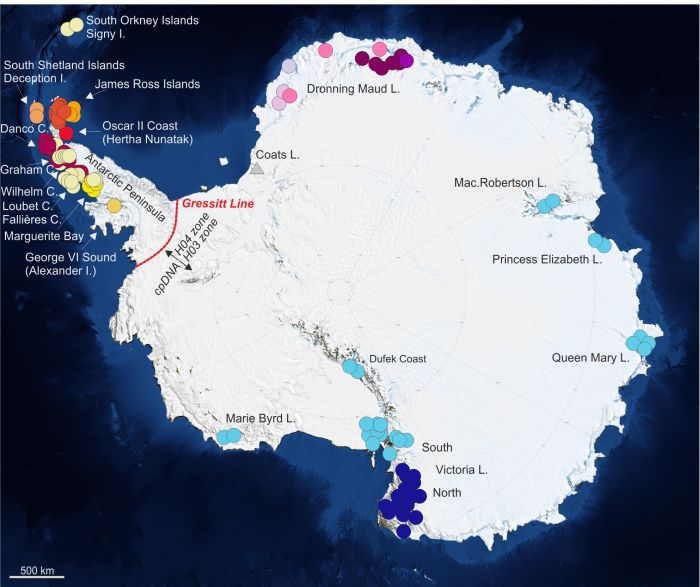

Syntrichia sarconeurum is one of the few moss species found in almost all accessible land areas of Antarctica. Based on molecular dating, the research team determined that this moss may have been present in Antarctica through a number of glacial periods, perhaps even throughout the Quaternary - that is, for over two million years. This means that it survived global climatic oscillations - warming and cooling.

Roniker continued: “We have unequivocally shown that the populations of this species persisted during the glacial peaks - the most difficult environmental conditions - not only on the outskirts of Antarctica (called Maritime Antarctica), but also in its heart, on the continent. This is evidenced by separate and isolated genetic lines of the continental populations.”

He emphasised the important role of Dr. Marta Saługa, who obtained and analysed data from almost all available herbarium specimens as part of her doctoral project. It involved a lot of painstaking work, but guaranteed that the material was comprehensive.

He added: ’Understanding how biodiversity was formed and maintained in the Antarctic - as well as other regions particularly vulnerable to climate change - is important. By learning about the historical dynamics of biodiversity of these particularly sensitive regions, we have a chance to predict what the future of biodiversity in these regions may be.”

The team is not planning a new expedition to Antarctica, but according to the scientist, it will continue to explore the available herbarium materials and apply the latest research methods that will allow to obtain a 'higher resolution of research results'.

Roniker said: “The latest sequencing methodology allows us to obtain much more information, even from very degraded genetic material. We hope for even more detailed analyses of what has happened to specific populations in Antarctica. We are preparing the publication of further papers in scientific journals.”

The research was carried out as part of a project funded by the Polish National Science Centre.

PAP - Science in Poland, Urszula Kaczorowska

uka/ zan/ kap/

tr. RL