Scientists from Poland, Germany and the US examined the unusual-looking bones of prehistoric marine reptiles from a site near Winterswijk in the Netherlands. According to the researchers, the record of pathologies such as diseases and injuries can provide insight into the functioning of healthy individuals from 250 million years ago.

The paper 'Bone abnormalities in the middle Anisian marine sauropsids from Winterswijk' by a team co-led by palaeontologist Dr. Dawid Surmik from the Faculty of Natural Sciences of the University of Silesia and Dr. Nicole Klein from the University of Bonn was recently published in the Journal of Morphology (https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/jmor.21550?af=R). The study was financed by the Polish National Science Centre.

Numerous marine reptile fossils have been found for over 70 years in Winterswijk and new finds are still being discovered. According to Dr. Klein, this makes it a perfect place for palaeopathological research.

Dr. Klein adds that among thousands of bones, the researchers found only four that showed abnormalities, which in itself was an astonishing and very telling result.

According to the researcher, Winterswijk represents a unique coastal to neritic environment within the Triassic epicontinental sea.

In the early Middle Triassic (251.9 to 247.2 million years ago), this part of Europe was covered by a shallow and warm sea, rich in organic life, in which various marine reptiles reigned. Their petrified bones are now found there in large numbers. Among them are the remains of nothosaurs, large marine reptiles and macropredators of the time.

Nothosaurs had dorsoventrally flattened bodies, somewhat resembling lizards, but they were not lizards - the term nothosaurus means 'false lizard' and was given to these animals because of this superficial resemblance. Surmik and Klein's team studied the unusual-looking bones of nothosaurs.

“Pathologies occasionally identified in fossil skeletal remains give us insight into the health of extinct vertebrates and are a valuable source of knowledge about the life of these animals. However, the diagnosis of pathology is sometimes burdened with overinterpretation,” Surmik says. He adds that many factors may contribute to misinterpretation, including unusual ossification, post-mortem damage and geological processes.

That is why unusual-looking bones were the subject of the team's study. Researchers examined a mandible of nothosaurus, which shows traces of a healed fracture, which means that despite damage to the feeding organ, the nothosaurus survived and could still hunt.

“These prehistoric reptiles seemed to apply the +all or nothing+ strategy, meaning that the hunt was either successful and the prey was swallowed whole, or the prey got lucky and escaped,” Klein explains.

“In the case of our injured nothosaurus, it could not make quick, snapping jaw movements to fragment its prey, because then the lower jaw would be constantly subjected to intense movements and would not be able to heal, which would result in the death of the animal,” adds Surmik. “Meanwhile, the animal survived and the wound healed, as evidenced by the signs of regeneration of this injury.”

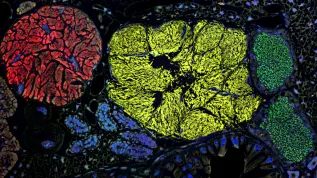

Another pathology identified by the researchers is fibrous bone dysplasia, a type of benign tumour that affects the bones, in this case, the rib of another nothosaurus. According to the University of Silesia press release, this is the first documentation of this condition in the fossil record. However, the causes of the disease, which also affects modern vertebrates including humans, remain unknown.

Professor Bruce M. Rothschild of the Carnegie Museum of Nature History in Pittsburgh explains that this pathological change is manifested by the presence of a pronounced thickening on the rib. Examination of the microstructure reveals that it is not a seemingly more obvious fused bone fracture, which manifests itself in a similar way (the presence of callus), but a rare bone tumour, fibrous dysplasia.

“The pathology record can give us great insight into the normal functioning of healthy individuals, as it can reveal whether certain diseases, malformations or serious injuries affected locomotion or food acquisition and whether they could be compensated in various ways,” concludes Dr. Tomasz Szczygielski from the Institute Paleobiology of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Warsaw.

“This is important because it provides us with independent evidence concerning the life of prehistoric animals, in addition to their anatomy, which is sometimes difficult to interpret or insufficiently preserved, and possible similarities with modern-day species, which are not always perfect,” Szczygielski adds.

PAP - Science in Poland, Mateusz Babak

mtb/ zan/ kap/

tr. RL