A diadectid was an amphibian that lived 300 million years ago in the area of today's Sudetes. Scientists have found a trace of its tail, on which they noticed rows of scales - like those of reptiles. The discovery suggests that the scales that helped animals enter and conquer the land evolved earlier than previously thought.

'This is the first historical evidence of the occurrence of epidermal scales in amphibians closely related to amniotes (organisms in which foetal membranes appear during embryonic development). The tail of the diadectid was not naked like in today's amphibians, but covered with rows of scales - such as can be seen in many reptiles. It turns out that animals still resembling amphibians in terms of their skeleton were most likely well adapted to functioning permanently out of water as adults. This complicates the idea of amphibians as amphibious animals and creates a wide field for new interpretations of their ecological role in the history of the Earth', says Dr. Izabela Ploch from the Department of Regional and Deposit Geology of the Polish Geological Institute - National Research Institute, co-author of a publication on this subject in the journal Biology Letters.

She adds that water-impermeable skin was one of the key features that paved the way for the first amniotes to fully inhabit lands, ensuring the future success of reptiles, birds and mammals. 'This feature is provided by a continuous epidermal layer, made of densely cross-linked proteins. The evolutionary development and time of appearance of this feature is very difficult to trace, because skin prints are extremely rare fossils. Our important discovery suggests that the beginnings of vertebrates' complete independence from water may be much earlier than previously thought’, Dr. Ploch says.

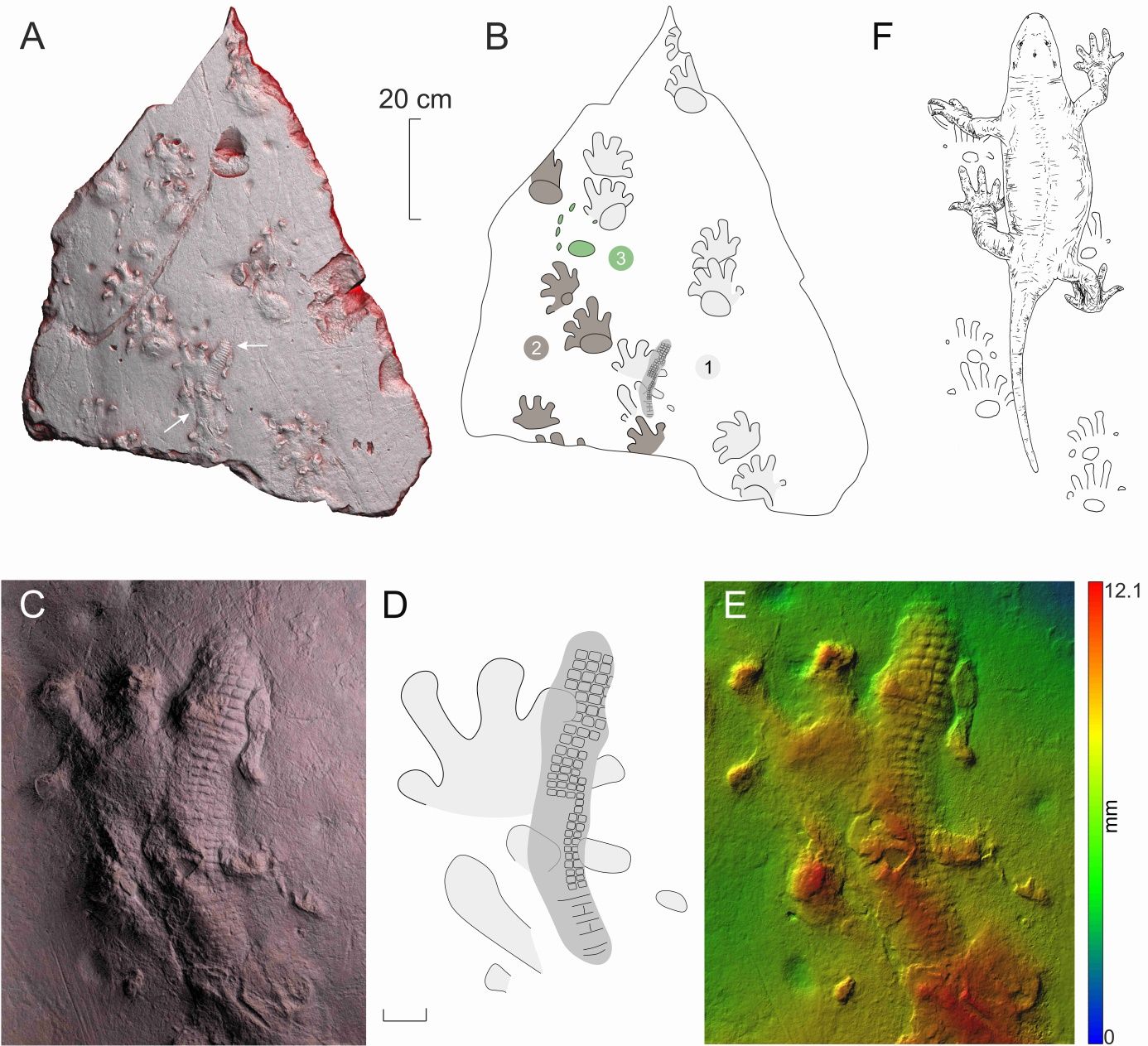

The imprints of the amphibian paws and tail were found during work in the active Piaskowiec Czerwony quarry near Nowa Ruda (Lower Silesian Voivodeship). 'Fossils are not only skeletons of organisms, but also various tracks left by them', Ploch says.

The prints were preserved on the surface of a sandstone bed dated to the Lower Permian. The place where they were found is the area of the Intra-Sudetic Basin, located in the central part of the Sudetes, on the Czech border. At that time, it was a sedimentary intra-mountain basin (i.e. an area naturally lowered in relation to the neighbouring areas), in which Carboniferous and Permian sediments of great thickness (large thickness of the rock layer) were preserved.

'Our unique find is an imprint of the tail skin of an amphibian from the diadectid group. They were quite large animals (their paw prints are the size of a human hand), which roamed the areas of today's Sudetes in the early Permian, leaving numerous tracks. The skin fragment is imprinted in the same layer as the tracks, next to the hind limb print. Based on the paw prints, we can assess, for example, how fast the animal moved; based on the skeleton, we know what its structure was, but now based on the tail print, we also know what kind of skin it had', says Dr. Ploch.

After combining all these known elements, it turned out that the animal had both amphibian and reptilian features, and the fossil shows another direction in which evolution could have gone.

'The skin prints indicate adaptive features of the body cover to periodically dry palaeoenvironments. We have added another piece to the puzzle of animal evolution - how and when scales began to appear on animal skins and how they adapted to changing climatic and environmental conditions', Dr. Ploch adds.

The international research team that made the discovery and described it included scientists from the Polish Geological Institute-National Research Institute, the Institute of Evolutionary Biology of the University of Warsaw, the Institute of Geological Sciences of the University of Wrocław, the Moravian Museum and Masaryk University in Czechia, the GEOSKOP Museum of the Prehistoric World and the Museum of Natural History in Germany. (PAP)

PAP - Science in Poland, Agnieszka Kliks-Pudlik

akp/ bar/ kap/

tr. RL