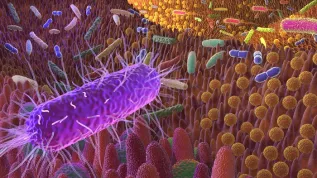

Harmful compounds produced by bacteria in the intestines enter the bloodstream and from there the brain, damaging neurons, shows a study by the Department of Microbiology at the Wroclaw Medical University.

The discovery may prove that metabolic endotoxemia, as well as long-term stress or improper diet, have a destructive effect on the functioning of the brain, consequently leading to the development of neurodegenerative diseases, among other things.

A team of scientists led by Professor Beata Sobieszczańska, head of the Department of Microbiology at the Wroclaw Medical University, has been conducting research on the intestinal microbiome for many years, determining its composition and the impact of bacterial metabolites on specific diseases. The previous studies focused mainly on the gut-heart axis and the relationship between the abnormal composition of intestinal microflora (gut dysbiosis) and cardiovascular diseases.

One of the studies that resulted in a doctoral dissertation analysed the microbiome of people with ischaemic heart disease. They had abnormal values of two metabolites produced by intestinal bacteria: endotoxin and indoxyl. This is a toxic duo that penetrates the blood, causing chronic inflammation of the endothelium of blood vessels. And from here it is a short way to the development of atherosclerosis and the related ischaemic heart disease.

'The impact of low, clinically insignificant concentrations of indoxyl and endotoxin on the endothelium of blood vessels had not been previously analysed, so this was an innovative study. We continued on this path. It is not a coincidence that we focus on the intestinal microbiome. Hippocrates stated over 2,000 years ago that most diseases begin in the intestines. His thesis, based on many years of observation of patients, has been confirmed by many modern scientific studies. We know more and more about the relationship between processes taking place in the intestines and disorders of other organs. However, we still do not know everything and we are discovering new areas,’ says Professor Sobieszczańska.

Scientists from the Wroclaw Medical University decided to further investigate the role of toxic metabolites of intestinal bacteria. Since in a state of intestinal dysbiosis they are able to enter the bloodstream and damage the endothelium of blood vessels, they must cause more damage to the body. This time, the researchers took a closer look at the gut-brain axis. No one had conducted such research before, which had its good and bad aspects.

'On the one hand, our research is pioneering, but on the other, we had no comparative material because there was no scientific literature to which we could refer. The results turned out to be extremely interesting. As we know, the blood-brain barrier prevents most substances from penetrating the central nervous system. Outside this barrier, the +guardians+ of the brain are microglia cells that react immediately in the event of a threat, organizing chemical defence against the intruder,’ says Professor Sobieszczańska.

She adds that unfortunately this barrier is imperfect and it fails in certain situations. 'We have discovered that metabolic endotoxemia, i.e. very low levels of endotoxin combined with the presence of saturated fatty acid in the serum, stimulates macrophages, as well as human brain microglial cells, to produce pro-inflammatory cytokines and oxygen radicals. Inflammatory mediators released by macrophages can lower the blood-brain barrier, opening a direct path to the brain for bacterial metabolites,’ she says.

The study showed that while saturated fatty acid did not increase the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines by endotoxin-stimulated microglia, it did enhance oxidative stress and the production of prostaglandin PGE2, a key factor in the activation of pathways contributing to neurotoxicity.

Saturated fatty acids are a component of a proper diet, so why do they turn out to be destructive to the brain? Professor Sobieszczańska explains that the key to understanding this mechanism is the word 'balance'. The saying 'too much of anything is unhealthy' has strong foundations in every sphere of life, including the hidden one. Our intestines are inhabited by billions of microorganisms, each of which has its own role. It is a myth that some of them are absolutely beneficial and others are absolutely not.

'No excess in intestinal flora is beneficial, a deficiency is not either. It turns out that even probiotic bacteria, such as Lactobacillus, which are generally considered healthy and necessary for the proper functioning of the intestines, can be harmful. They occur naturally in pickles and yogurts, and are usually supplemented during antibiotic therapy. However, it has been shown that the excess lactic acid produced by these bacteria modulates metabolic hormones - leptin and ghrelin, which leads directly to insulin resistance, obesity and related diseases,’ says Professor Sobieszczańska.

The production of harmful metabolites occurs not only as a result of a poor diet. The bacteria living in the intestines are also extremely sensitive to other factors. One of the most important factors is stress, even a short-term one. During stress the body secretes stress hormones, e.g. cortisol. It has been shown that as a result of their action, the intestinal environment changes, making it unfavourable for probiotic bacteria, which causes them to escape for up to a week. And this is a result of short-term nervousness about some temporary situation. What happens in our intestines when we live in constant stress?

If metabolites of intestinal bacteria damage neurons, perhaps their role in causing brain disorders is greater than we might have expected? Professor Sobieszczańska believes that this is undoubtedly the opening of a new scientific path.

In highly developed societies, we have had an epidemic of neurodegenerative diseases in recent years. It is not only Alzheimer's disease, Parkinson's disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis or dementia, but a whole spectrum of other diseases related to damage to cells of the nervous system.

'We do not know why the number of these patients is increasing, but we do know that this does not concern the populations of less developed countries. Neurodegenerative diseases are less common there. This leads to the assumption that the culprit is the Western lifestyle, the quintessence of which is the consumption of highly processed products, rush, stress and lack of contact with nature', the researcher adds.

It has already been proven that in the group of patients with diabetes (another lifestyle disease that has become an epidemic) the percentage of dementia patients is higher than in the entire population.

'However, this is just a statement of fact that does not explain why this is happening. We, microbiologists, are looking for the answer to this key question in science at the level of the smallest organisms that our body hosts. I am convinced that this is where we will find the answer,’ says Professor Sobieszczańska.(PAP)

PAP - Science in Poland, Roman Skiba

ros/ mhr/ kap/

tr. RL