The costumes of kings, royal mothers and a bishop from medieval Nubia have been reconstructed by Polish scientists and designers based on paintings that once decorated the walls of the cathedral in Faras. This unique collection of oriental fashion were presented at the Louvre in Paris on October 17.

Archaeologists from the University of Warsaw and designers from the SWPS University undertook the reconstruction of medieval costumes. The result of their work is the reconstruction of five Nubian costumes based on paintings from the cathedral in Faras, which are currently in the collection of the National Museum in Warsaw and the National Museum of Sudan in Khartoum.

The costumes were presented for the first time at the Musée du Louvre’s 'Midis de l’archéologie!'.

Faras was one of the capitals of the medieval kingdom of Nobadia, and after its unification with the kingdom of Makuria, the capital of the northern province. The United Kingdom of Makuria existed in the lands that are now southern Egypt and northern Sudan between the 6th and 14th centuries. It was part of a historical region called Nubia. Polish research in these areas was initiated by Professor Kazimierz Michałowski from the University of Warsaw in the 1960s. The discovery of the cathedral in Faras together with a group of unique paintings gave rise to studies that are still a Polish domain today, and a unique exhibition of medieval art from Nubia is located in the Faras Gallery at the National Museum in Warsaw.

An important element of the decor of Nubian churches were monumental images of representatives of the court and clergy. They were intended to influence the faithful and show them the connections between the kingdom and the Church, as well as the divine source of power. Just like today, robes and decorative elements of clothing belonged to a non-verbal communication system, in which each element had a meaning.

'We have practically no preserved, complete costumes from Nubia. One tunic and bishop's trousers have survived, but usually we only find fragments of clothing, because fabrics are extremely rare at archaeological sites. On the other hand, we also have a huge deficit of written sources concerning this place and originating from Nubia', says Dr. Dobrochna Zielińska, an archaeologist from the Faculty of Archaeology at the University of Warsaw. In order to reconstruct the Nubian costumes,

Dr. Zielińska together with Dr. Karel Innemée and Dr. Magdalena Woźniak-Eusèbe reached for iconographic sources. They became the researchers' primary source of knowledge in the project 'Creations of power. The image of the royal family and the clergy in medieval Nubia' carried out at the University of Warsaw, financed by the Polonez BIS programme of the National Science Centre.

Royal ambitions recorded in costumes

'For reconstruction, we selected primarily two royal costumes and two costumes of royal mothers (from the 10th and late 12th centuries). They showcase the change brought to Nubia by Christianity, which came from Constantinople in the 6th century. We believe that the ambition of the Kingdom of Makuria was to join the Christian world. And these ambitions are visible in the costumes. Especially at the beginning of Christianisation, all elements of royal costumes mirror the costumes of Byzantine emperors', says Dr. Zielińska.

Silks appeared over time among the fabrics, which was a general trend, because the Byzantine emperors also began to use luxurious fabrics that came from the East. In the 12th century royal costume, references to elements that were important in folk beliefs are already visible. In the 12th century, the Kingdom of Makuria was more aware of its own tradition. 'Hence, for example, the moon appears on the royal crown. This is not the influence of Islam, but a local symbol that we already know from earlier eras and an element of the philosophy of seeing the world', Dr. Zielińska says.

Woman - transferring power

The situation with the attire of royal mothers is slightly more complicated. Dr. Zielińska explains that in African cultures, including the Nubian culture, it was women who transferred power. The ruler was therefore not the son of the king, but the son of the king's sister. In the Byzantine Empire, there was no such function and position at court. The attire of the royal mother in Nubia was therefore adapted to the needs of this very important function.

'Both women's costumes are richly decorated. Each element of the robe is decorated differently, but put together everything creates a harmonious whole, maintained in golden and earthy colours, and deep blue. The royal mother also has an absolutely unique crown topped with a pair of wings', Zielińska says. Researchers assume that this may be a distant reference to the crown of Isis - the goddess of fertility and protector of families in Egyptian mythology.

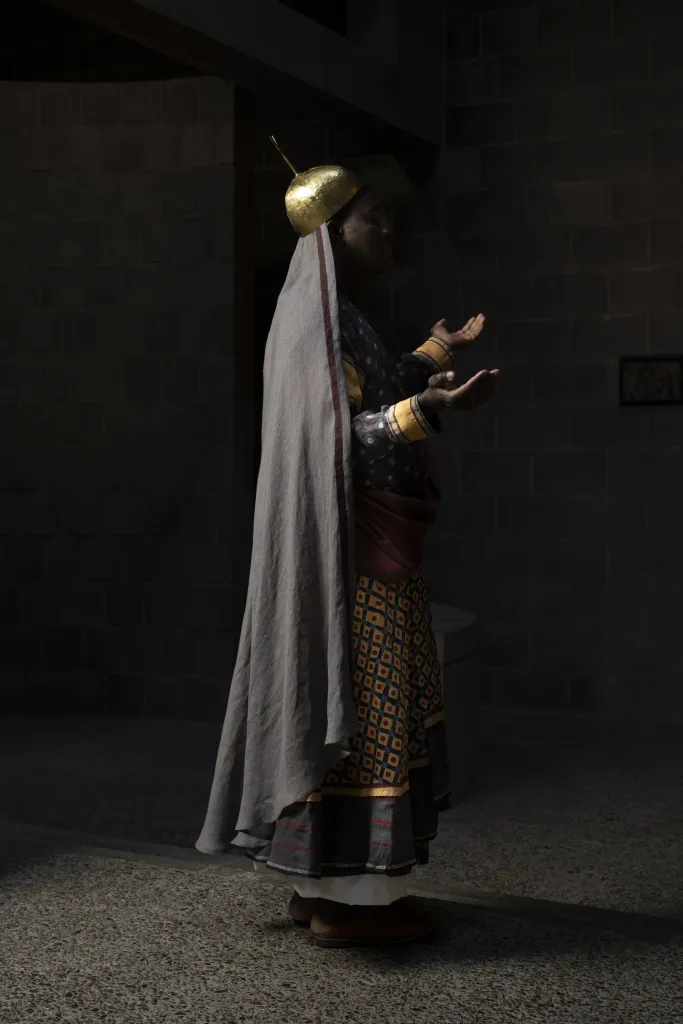

The later costume of the royal mother has elements of the Eastern style. The woman is dressed in a tunic and an outer robe, draped around the figure. 'Women in Sudan still wear a tunic, this is the traditional outer layer, which is put on when leaving the house, but also when entertaining guests. It is an elegant robe, but also a very practical one, because it protects against dust, sun, wind', says Zielińska.

130 bishop's bells

She adds that the bishop's costume is much more uniform than the court costumes. The Nubian Church preserved what it received from Constantinople in the 'Christianisation package' and, apart from details, there are no major changes visible over the centuries in the costumes of church dignitaries.

'However, one of these changes made a huge impression on us. The bishop's attire was decorated with 130 brass bells, so when the bishop walked, we could hear him immediately. We only became aware of the role of these bells when reconstructing the attire. The bishop's attire therefore is quite heavy, because while a single bell is very light, 130 bells weigh quite a bit', Dr. Zielińska says.

Experimental archaeology

The first task of the team of scientists working on the reconstructions was to recreate the historical colours of the royal and priestly robes. This was achieved thanks to archaeological research by Dr Magdalena Woźniak-Eusèbe from the University of Warsaw and the experience of Dr Katarzyna Schmidt-Przewoźna from the Faculty of Design at the SWPS University in dyeing fabrics with traditional methods and natural dyes.

'That was where our adventure began. We wanted to see if we could use natural dyes to obtain the same colours as in the paintings. Was it the painter's fantasy or was it based on reality? And that was the first moment that took our breath away. When we received the entire colour palette, we took the samples to the Faras Gallery in the National Museum in Warsaw and it turned out that the shades matched exactly’, says Dr. Zielińska.

From the colour palette proposed by Dr. Schmidt-Przewoźna, costume designer Dorothée Roqueplo and Dr. Agnieszka Jacobson-Cielecka from SWPS University selected the shades that were closest to the original colours, using the collections of original fabrics from Nubia at the Textile Research Centre in Leiden (NL) and the paintings from Faras at the National Museum in Warsaw.

Patterns printed by stamps, hand embroidery and appliqués were applied to the fabrics dyed according to the colour palette. The most demanding task was to translate the two-dimensional, not always legible paintings into three-dimensional forms and understand the arrangement of the layers that made up the costume, including those that were not visible on paintings, but known only from tradition or other sources, including knowledge of Christian rites.

'In further work, it was necessary to combine various types of data, knowledge and, above all, intuition, imagination. Many decisions had to be made: what kind of fabric to sew a given element from; whether it was light, warm, stiff, or starched, because we know that starch was already used at that time. We can call this undertaking experimental archaeology', Dr. Zielińska says.

The reconstructed costumes were presented during a special session by Sudanese representatives of the community from the Netherlands and Germany. 'Especially now, during the tragic civil war in Sudan, our activities have a chance to remind the world that not only the wonderful inhabitants of this country, but also its rich heritage are particularly endangered today', the researchers say.

The beginnings of Polish research in Faras

In the 1960s, the Egyptian government decided to build the Great Dam in Aswan. In order to study the areas threatened by flooding by the Nile, scientists from 26 countries participated in the UNESCO-sponsored campaign to save historical monuments. The Polish team, led by Professor Kazimierz Michałowski from the University of Warsaw, chose the city of Faras as the research site.

The discovery of the Faras cathedral with well-preserved wall paintings was called the 'Miracle of Faras' in the international press. The cathedral complex consists of religious buildings named after the bishops who commissioned their construction: Aetios, Paulos and Petros. A total of 169 wall paintings were discovered in the cathedral. These monuments are the largest group of Christian Nubian paintings ever found, and present its development from the 8th to the 13th century. (PAP)

PAP - Science in Poland, Ewelina Krajczyńska-Wujec

ekr/ agt/ kap/

tr. RL

Gallery (8 images)

-

1/8Credit: Paulina Matusiak, Eddy Wenting

1/8Credit: Paulina Matusiak, Eddy Wenting -

2/8Credit: Paulina Matusiak, Eddy Wenting

2/8Credit: Paulina Matusiak, Eddy Wenting -

3/8Credit: Paulina Matusiak, Eddy Wenting

3/8Credit: Paulina Matusiak, Eddy Wenting -

4/8Credit: Paulina Matusiak, Eddy Wenting

4/8Credit: Paulina Matusiak, Eddy Wenting -

5/8Credit: Paulina Matusiak, Eddy Wenting

5/8Credit: Paulina Matusiak, Eddy Wenting -

6/8Credit: Paulina Matusiak, Eddy Wenting

6/8Credit: Paulina Matusiak, Eddy Wenting -

7/8Credit: Paulina Matusiak, Eddy Wenting

7/8Credit: Paulina Matusiak, Eddy Wenting -

8/8Credit: Eddy Wenting

8/8Credit: Eddy Wenting