Detailed information about various networks of paint cracks in paintings was provided by scientists working on the 'Grieg Craquelure' project. During the research, scientists from Krakow were also the first in the world to determine the properties of a paint typical of pre-Renaissance Italian painting - egg tempera.

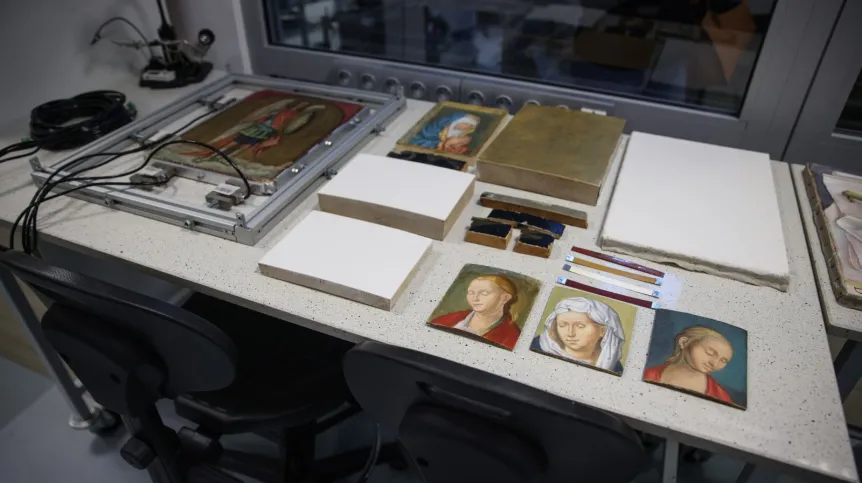

As part of the recently completed project, researchers from the Polish Academy of Sciences, the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków, the Wawel Royal Castle and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim analysed the networks of paint cracks visible in paintings from the Renaissance period.

'When looking at paintings, we look at what is depicted in them, but few visitors see the network of cracks, which is very characteristic and typical of the place where the painting was created, the technique and technology used by the artist, as well as the entire history of storage of the work of art,’ Dr. Aleksandra Hola, chief conservator of the Wawel Royal Castle and assistant professor at the Faculty of Conservation and Restoration of Works of Art of the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków told a press conference at the Polish Academy of Sciences in Kraków.

The scientists' goal was to explain how networks of cracks formed in paintings and solve the mystery of their various patterns.

'Conservators intuitively associate crack networks with certain phenomena, but until now there has been no structured language that would describe this crack networks, said Dr. Hola.

According to the researchers, these networks, which are systems of cracks, can take on various shapes; parallel lines, rectangular, square, round, grids without any order are also observed. The project allowed scientists to understand how they formed and why, for example, The Last Judgment by Hans Memling has a different crackleure than Madonna under the Fir Trees by Lukas Cranach the Elder, and different still to Lady with an Ermine by Leonardo da Vinci.

'The material properties, as well as the climate in which the objects have been stored, largely determine the type of cracks that appear. The network of cracks develops differently in a painting created in the south of Italy than in one painted in Norway. It is also influenced by the thickness of the (painting) layer and the arrangement of these layers - which is why we say that crack networks are characteristic of different art schools and the periods in which they were created,’ said Professor Łukasz Bratasz from the Jerzy Haber Institute of Catalysis and Surface Physicochemistry PAS. 'The patterns are a characteristic fingerprint of both the artist and the school the artist comes from, the time in which the object was created and the material the artist used,’ he added.

The researchers emphasised that understanding the process of crack formation can contribute to the correct assessment of the originality of paintings and better identification of forgeries. 'We can see which crack networks result from accelerated ageing, a technique used by counterfeiters, and which develop naturally. This opens the way to the creation of completely new tools for the authentication of objects,’ Bratasz said.

The second goal of the project was to determine the needs related to the protection of works of art with a developed crackleure. To do this, researchers first had to determine the properties of the materials used by artists. 'Engineers open a book and can easily find the properties of materials. In the case of cultural heritage objects, the properties of Leonardo's oil paint are not known. This was the goal of the project. For the first time in the world, we determined the properties of egg tempera, so important for Italian painting,’ Bratasz said.

Ultimately, the study proved that paintings with a developed network of cracks were much less sensitive to microclimate instabilities than previously thought. 'Objects with a developed crackleure do not need very restrictive conditions. This opens the way to reducing energy consumption in museums and promoting the implementation of the idea of a +green museum+, i.e. an institution that, while caring for the treasures of the past, also cares for the natural environment and the future generations,’ Bratasz continued.

The 'Grieg Craquelure' project involved 15 experts in various fields of science, including specialists from the Wawel Royal Castle, the Jerzy Haber Institute of Catalysis and Surface Physicochemistry PAS, the Faculty of Conservation and Restoration of Works of Art of the Academy of Fine Arts in Kraków and the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim. The scientists examined existing works of art: Madonna under the Fir Trees by Lukas Cranach from the collections of the Archdiocesan Museum in Wrocław, The Last Judgment by the follower of Hieronymus Bosch from the collections of the Wawel Royal Castle and Madonna and Child from St. Mary's Basilica in Krakow. (PAP)

PAP - Science in Poland, Julia Kalęba

juka/ dki/ kap/

tr. RL