More and more new chemical substances are entering the sewage system - from medicines, cosmetics, plastics. According to Monika Żubrowska-Sudoł, PhD, from the Warsaw University of Technology, their separation and safe disposal from wastewater treatment plants is a huge problem.

Biocidal detergents, chemicals used in industry, pharmaceuticals, pesticides, cosmetic ingredients, substances from car repair shops, hospitals, farms - people use thousands or even millions of different chemical compounds, the residues of which then end up in wastewater.

Contaminants of emerging concern, or micropollutants, are substances that appear in wastewater in quite low concentrations, which makes them seem relatively harmless. However, these compounds gradually accumulate in wastewater treatment plants and in the environment. And only then do we see how serious a challenge they are.

'Micropollutants have not appeared in wastewater in recent years. These pollutants have been present in wastewater for a long time, but we did not know about their presence and did not have as much knowledge about their harmfulness as we do now. It is only for a dozen or so years that we have had analytical tools that enable us to find small amounts of substances in the tested samples. We also know that these pollutants should not be allowed to migrate into the environment', says Monika Żubrowska-Sudoł, PhD, a professor at the Faculty of Building Services, Hydro and Environmental Engineering of the Warsaw University of Technology. In her opinion, the entire life cycle of a product that hits the market must be carefully observed - 'from the cradle to the grave'. And some of the new compounds are insufficiently tested and it is not yet known how to dispose of them.

On November 5, 2024, the EU adopted a directive on municipal wastewater treatment. Among other things, it introduces extended manufacturer responsibility for products introduced to the market, which translates into the 'polluter pays' approach. According to this principle, manufacturers of cosmetics, medicines, and chemicals, among others, will have to take on part of the costs of removing micropollutants from wastewater. The changes are to take place by 2035.

'This is a very big step forward, because the industry will look differently at the harmful substances it creates', comments Monika Żubrowska-Sudoł. However, she points out that we are not yet able to effectively neutralize some of the substances that are necessary for humans and are present on the market.

MICROPLASTICS

One of the groups of substances that wastewater treatment plants cannot handle are microplastics. They come from plastic packaging, are found in the composition of cosmetic products and synthetic fabrics. A lot of microplastics are also released into the water during washing clothes made of synthetic fabrics (e.g. fleece, nylon, polyester). 'It may seem that processing plastic packaging into fleece sweatshirts or blankets is an ecological trend, because we get rid of waste. But clothes generate microplastics, too', the expert points out.

According to Żubrowska-Sudoł, European wastewater treatment plants are not yet required to remove microplastics. Purified wastewater that ends up in rivers and seas contains these small particles that will remain in the environment for a very long time. The expert reminds that microscopic pieces of polymers not only interact with the body (they can, for example, negatively affect the hormonal system), but also collect pollutants - other pollutants are absorbed on their surface, and bacteria also develop on them.

MEDICINES

Another source of micropollutants are pharmaceuticals, e.g. painkillers, anticancer drugs, hormones, antibiotics, as well as veterinary drugs and illegal drugs.

Pharmaceuticals are not completely neutralized in wastewater treatment plants. They end up in rivers, which can affect the functioning of animals and plants - and we know, for example, that even low concentrations of some hormonal drugs can also affect the development and reproduction of fish and amphibians.

In turn, antibiotics flowing in the sewage system and then in rivers in low concentrations allow bacteria to come into contact with a substance that is dangerous to them, but in low concentrations, and provide them with conditions to prepare defence mechanisms against the antibiotic. If, however, such an antibiotic-resistant bacterium that evolved in wastewater enters the body, we will not be able to fight it with that antibiotic. As a result, we will forever deprive ourselves of our defence against bacterial diseases.

'Antibiotics save our lives and we as humanity cannot stop using them. However, we can more efficiently select antibiotic doses for individual patients to minimize the amounts of the drug that end up in wastewater', the expert comments.

Another problem is that there are people who flush expired medicines down the toilet, although such substances should go into containers in pharmacies. A separate challenge is the overuse of veterinary medicines in farming industry.

FOREVER CHEMICALS

Chemical compounds that are extremely durable also end up in wastewater. These include PFAS, or perfluoroalkyl compounds. They are sometimes called forever chemicals, because they contain some of the strongest chemical bonds known to us (between carbon and fluorine).

People already produce millions of different compounds from the PFAS group. It is already known that PFAS have a carcinogenic, mutagenic effects, can be harmful to developing foetuses, and some of these compounds also cause mental illnesses. PFAS are used in Teflon pans, food packaging (e.g. pizza boxes), feminine hygiene products, clothes, mobile phones, cosmetics, toilet paper.

'We do not yet know how to effectively remove these substances from wastewater. Research in this area is only just underway. However, I wonder how such substances were allowed reach the market. It would be best not to introduce them at all, or, where possible, withdraw them and look for substitutes', Żubrowska-Sudoł comments.

MICROPOLLUTANTS IN A WASTEWATER TREATMENT PLANT

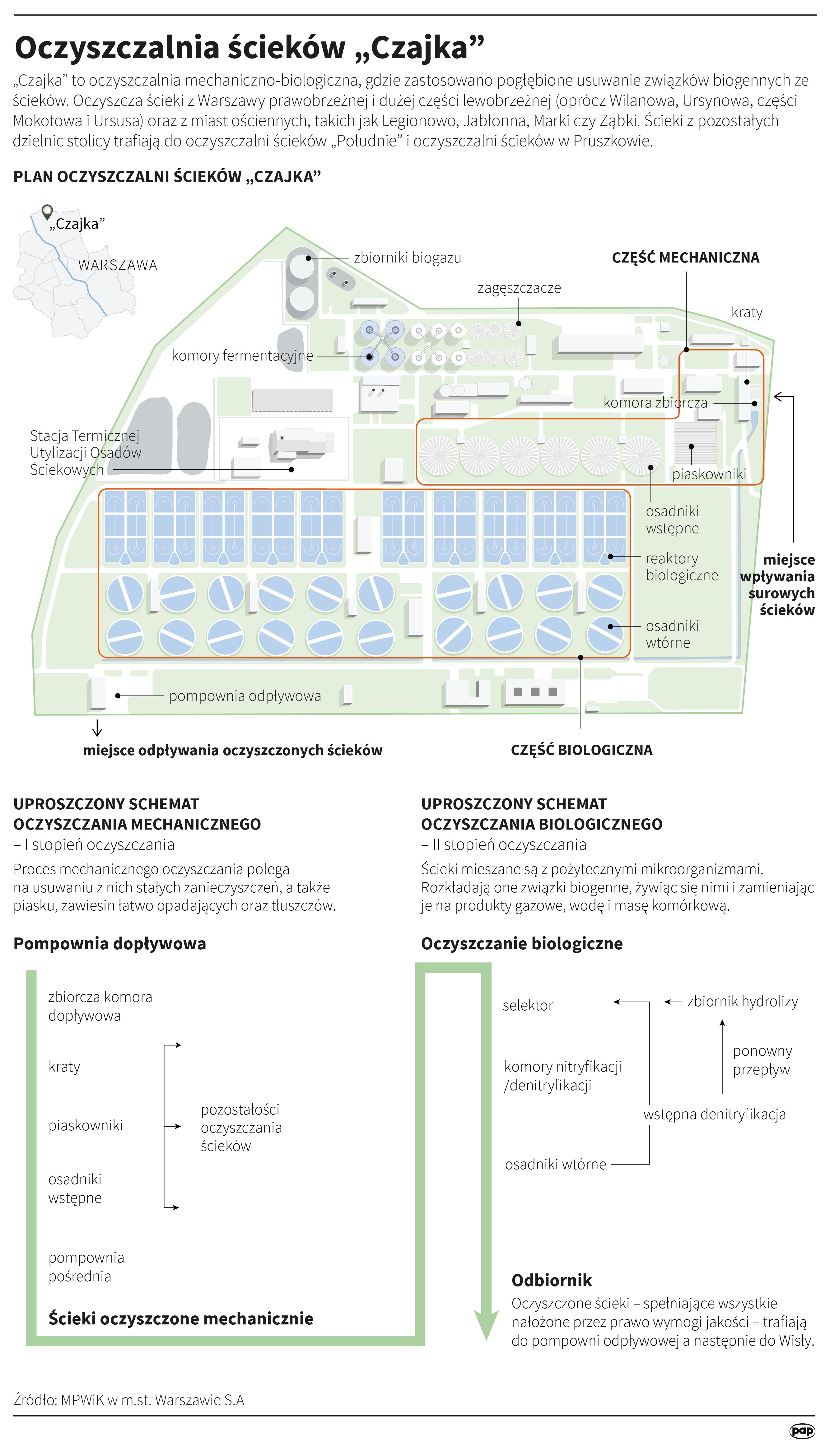

A wastewater treatment plant usually consists of a mechanical part, in which larger pollutants and fats that are insoluble in water are separated from wastewater. The next part contains bioreactors, where matter is decomposed by microorganisms. Some treatment plants also have a chemical part, in which mainly phosphorus is removed. And the next part is the sediment part, in which sediments, waste generated in treatment plants, are processed.

The new wastewater directive does impose the removal of micropollutants from wastewater in large wastewater treatment plants, but this only applies to selected substances. For example, membrane (retention of pollutants) and sorption (absorption of some materials - like a sponge - by others) methods are used. Thanks to this, selected harmful compounds are not released into the environment in treated wastewater. However, the rest of the micropollutants end up in rivers, seas and soil.

Żubrowska-Sudoł points out that in addition to micropollutants that are originally found in wastewater, compounds that are intermediate products of transformations used during wastewater treatment are equally dangerous to human health and the natural environment. In many cases, these compounds are more harmful than their precursors. Some of the latest scientific reports confirm this the researcher hopes they will be used in practice.

Another issue is that sewage sludge from treatment plants can be used to produce compost, fertilizers or soil improvers. The presence of micropollutants in such products is undesirable, because when they end up in the environment, they pollute soil and water.

'Each of us has an impact on what ends up in wastewater, because wastewater is water used by humans. What we use in our lives therefore affects the quality of wastewater', Żubrowska-Sudoł says. In her opinion, public education is needed, because simple changes in attitudes can make a huge difference.

The expert from the Warsaw University of Technology advises how to reduce the amount of micropollutants in wastewater: do not treat the sewage system like a rubbish bin, pay attention to the composition of the products you buy, choose products (including clothes) that have a biodegradable composition, avoid companies that avoid responsibility for the pollution they introduce into the environment.

PAP - Science in Poland, Ludwika Tomala

lt/ agt/