Palaeontologists examining the fragment of a 215-million-year-old jaw have found it had two double-rooted teeth belonging to a previously unknown shrew-like mammaliaform.

The 2cm bone fragment was discovered in 2014 in eastern Greenland by Dr. Grzegorz Niedźwiedzki from the University of Uppsala (Sweden). It took several years to analyse the find but it soon turned out that scientists were dealing with the remains of a previously unknown mammaliaform species.

Dr. Tomasz Sulej from the Institute of Paleobiology of the Polish Academy of Sciences who headed the expedition to Greenland said: “We knew immediately that we were dealing with an important discovery. Expert analyses were not needed for this, which is often the case with such small palaeontological finds.”

The discovery of a new mammaliaform species is a unique event, as according to Sulej, only about ten mammaliaform species are known from such an ancient period. He also points out that the oldest similar finds are about 5-10 million years younger.

The new species has been named Kalaallitkigun jenkinsi as scientists wanted to honour the indigenous people of Greenland, the Inuit, in whose language the word Kalaallitkigun means 'a tooth from Greenland'. In turn, the generic name jenkinsi refers to the achievements of the American researcher F.A. Jenkins, one of the pioneers of palaeontology in Greenland.

Sulej said: “Describing another mammaliaform species is huge luck, especially that an American mission operated in the same place in the 1990s. But they had to finish the research prematurely, because a storm threw their camp into the sea. We had no such problems.”

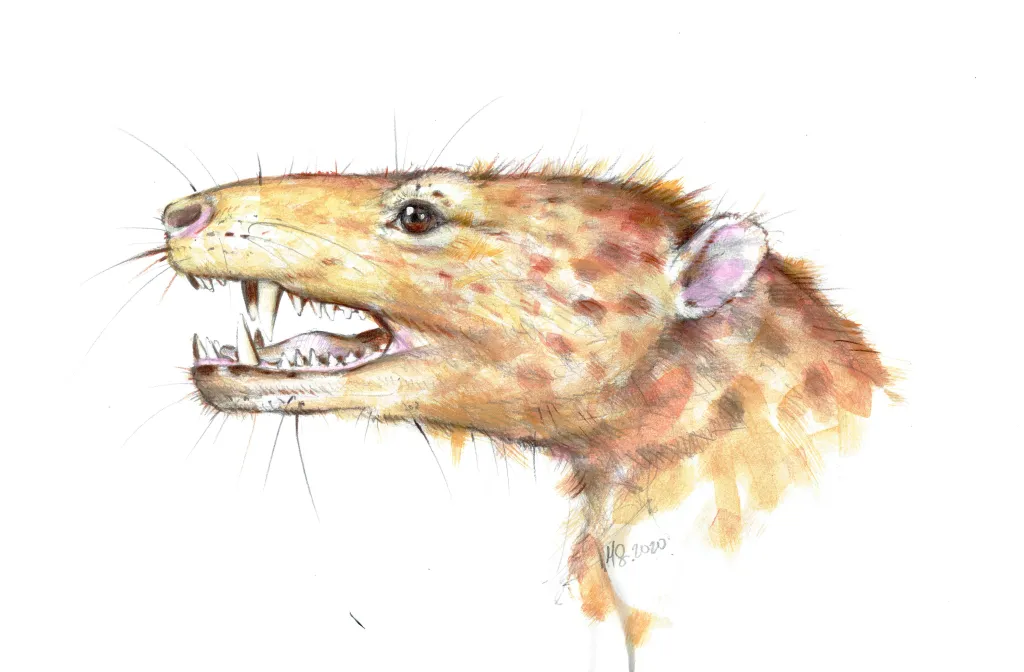

Even a small fragment of a skeleton can provide scientists with a lot of information about the appearance and life of an animal. According to Dr. Sulej, K. jenkinsi may have resembled today's shrews in terms of size and way of life.

The scientist says that although it was only possible to find a tiny fragment of the animal's fossil, the mandible, it is in fact the most important fragment for palaeontologists, because it changed the fastest during the evolution of mammaliaforms.

Sulej said: “In more primitive animals, the mandible consisted of many bones, and in our case we are talking about one bone. Earlier species had single-rooted teeth, ours has two roots.”

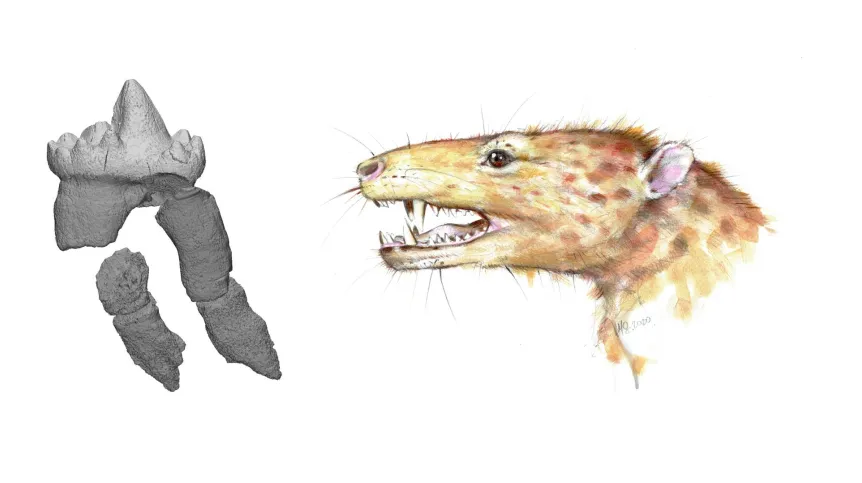

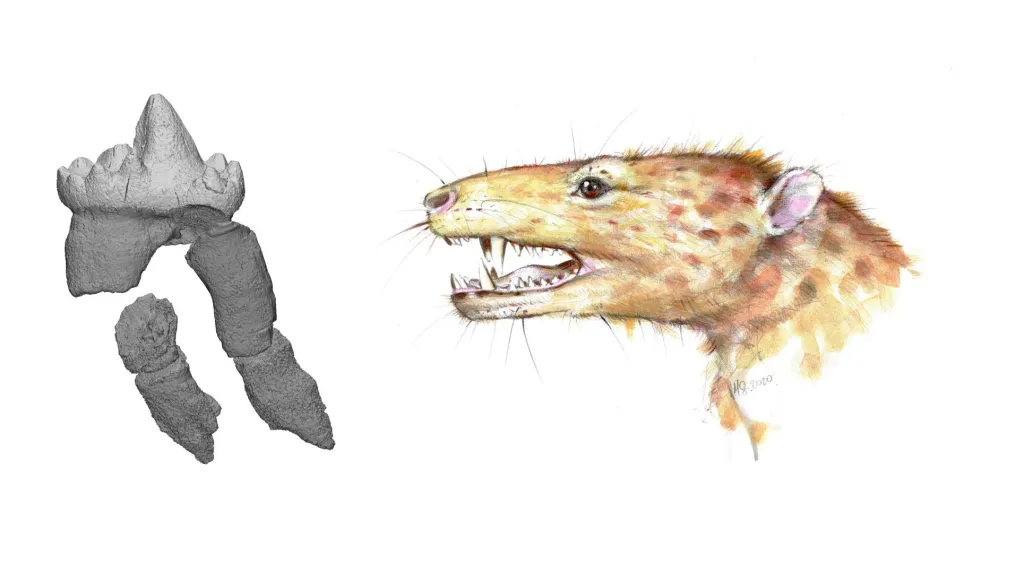

Experts from the Warsaw University of Technology made 3D models of two teeth - a double-rooted one, belonging to K. jenkinsi, and another with the same crown, but only one root, which belonged to an earlier species.

The scientists then checked how such teeth 'worked' in the mandible. Sulej said: “We found that the teeth and lower jaw of the mammaliaform we had discovered were more durable,” adding that K. jenkinsi could be a transition stage between species eating mainly insects and those eating mainly plants.

The life of the Kalaallitkigun was not easy, as it lived among the first known predatory dinosaurs that could hunt it. The mammaliaform would escape them by hiding among numerous ferns and other bushes, as there were no grasses or flowering plants at that time. Nor was there Greenland as we know it now. There was a great supercontinent known as Pangaea, which gradually broke apart into smaller parts.

The discovery site is reminiscent of the surface of Mars as the stones are blood red. “These are the so-called continental inland sedimentary rocks, and the source of their specific colour is iron oxidation. Land sediments from 215 million years ago have this colour all over the world, Such deposits were formed when mudstones and claystones were deposited in lakes,” Sulej said.

The publication about the mammaliaform has just been published in the prestigious journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America (PNAS).

PAP - Science in Poland, Szymon Zdziebłowski

szz/ zan/ kap/

tr. RL

Gallery (3 images)

-

1/3Pic. Marta Szubert

1/3Pic. Marta Szubert -

2/3Pic. Marta Szubert, Daniel Snitting

2/3Pic. Marta Szubert, Daniel Snitting -

3/3Photo: Andrzej S. Wolniewicz

3/3Photo: Andrzej S. Wolniewicz