The people of Old Dongola (Sudan) recycled clothes because they knew that producing fabrics was very expensive and time-consuming. They dyed their clothes sparingly, but they especially liked the colour blue, which not only looked nice, but was also believed to protect against evil.

From the 5th to the 14th century, Old Dongola was the capital of Makuria, one of the most prominent states of medieval Africa. It was located in a historical land called Nubia, now in Egypt and Sudan. Research in this city was initiated by Professor Kazimierz Michałowski in 1964. Currently, intensive research in this place is conducted by scientists from the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology of the University of Warsaw (PCMA UW).

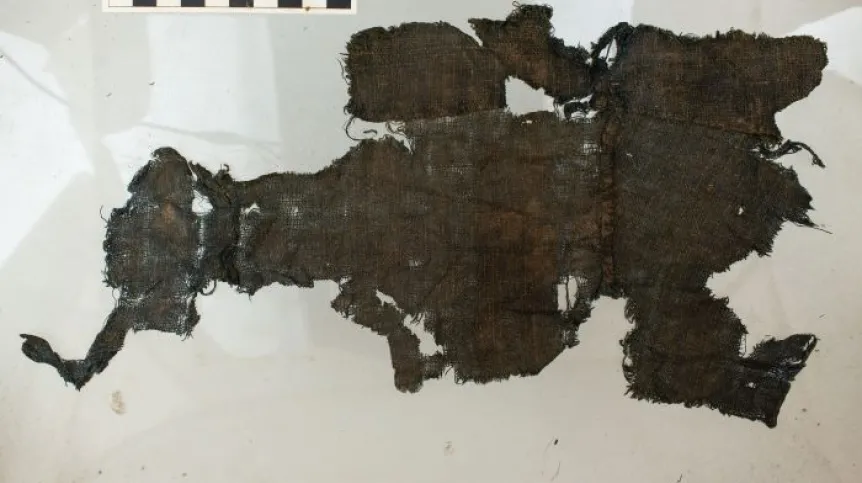

Dr. Magdalena M. Woźniak from the Polish Centre of Mediterranean Archaeology UW, together with scientists from the Faculty of Chemistry at the University of Warsaw, examined fabrics from the late period in the history of Old Dongola - from the 17th and 18th centuries. They were found in the urban part of Old Dongola, in residential spaces and garbage dumps. The results of the work, chemical analyses of 17 samples, were published in the journal Archaeometry. The research was financed by the European Research Council Starting Grant programme.

These are the first analyses of fabrics from this place. According to Dr. Woźniak, for many years the attention of researchers in Old Dongola focused on wall paintings. They mainly depict rulers and church dignitaries. However, few scenes also show average, ordinary residents. 'Fabrisc are a window that allows us to learn more about the lives of ordinary people of this city,’ the researcher says.

'It must be made clear that the people of Old Dongola loved recycling. They were aware of the value of the fabrics and tried to use them as much as possible. Before the industrial revolution, the production of fabrics was a very time-consuming activity. Once people had gone through this whole process: growing the cotton, harvesting it, spinning it, putting it on a loom, weaving it - they used the fabric until its last possible use. So, first it was used as clothing, then it was used for patches or rags, sometimes it served as a blanket, and sometimes as a plug in the wall to protect against the wind. So we find these fabrics in a very worn form,’ says Dr. Woźniak.

The ornamented edges of fabrics are best preserved. Thanks to dyeing, they looked nice, but they were also thicker, and therefore more durable, they wore out more slowly. In general, thanks to the dry climate of the Nile Valley, fabrics, leather and wood are quite well preserved in this area.

Thus, the preserved remains of recycled fabrics have become a rich source of information for the researchers from PCMA UW about the lives of the inhabitants, the production of fabrics and the ways they dressed.

Most clothes were made of wool. However, that wool was of slightly lower quality than what we currently use in clothes. In Sudan, sheep were most likely never farmed for wool, but rather for milk and meat. Wool was a secondary product, hence its lower quality.

'There is also a lot of fabrics made from cotton and there are indications that it was grown in this section of the Nile Valley. There is some linen, but surprisingly little of it. There are also fragments of silk, but they come from a single location identified as the home of a local ruler. This makes sense, only the elites had access to silk,’ says Dr. Woźniak.

Women mostly wore woollen clothes that were not sewn. It was usually a large piece of fabric that they wrapped around themselves in various ways. The edges of these fabrics, especially the most visible parts - such as the bottom part and the parts near the head - were decorated. The decoration often consisted of one strip that was 5 to 10 cm wide and ran along the entire edge of the fabric. Geometric patterns appeared on these decorated fragments in various colours: yellow, blue, red.

Men mainly wore cotton clothes made of sewn pieces of fabric and resembled dresses. The colour blue often appeared on them, which was liked and sought after. 'Blue had an additional meaning as a colour that protected people against evil. Children's tunics and collars were often trimmed with a strip of blue fabric. Not only did it look good visually, but it was also an amulet,’ Woźniak says.

Only the wealthiest residents could afford a fabric that was all dyed, e.g. blue. In general, colour was something rare, difficult to obtain and expensive. Large sheets of fabric were not dyed on a large scale. The amount of coloured threads was limited. They were dyed in tiny vessels, and when the appropriate amount was collected, the fabrics were decorated while weaving: either using the upholstery technique or the brooching technique.

Dyes of both plant and animal origin were used. Woad (Isatis tinctoria), a plant from the cabbage family, was quite commonly used for blue dyeing. Locally growing resedas gave yellow colour. The red colour was obtained by using local rose madder (Rubia tinctorum) and imported kermes (Kermes vermilio).

Local craftsmen also mixed various ingredients to obtain green or shades of orange. Some were applied directly to the fabric, others were fixed with special techniques using a mordant that helped maintain the colour.

Scientists also identified dyer's greenweed (Genista tinctoria) in the tested fabrics, which was used on a large scale in Europe at that time. They also found blue-dyed cotton, but it was often imported, primarily from Egypt. 'Many imported products reached Nubia during this period. Apart from fabrics, which accounted for more than half of imports, other desirable products reached Nubia through the Nile and the desert, including tin, lead, small metal products (razors, files, mirrors, scissors, needles, thimbles), spices and beads, some were even imported from Europe or distant India,’ says Dr. Woźniak.

She adds: ‘We have also found animal dyes that come from two species of hemipterans (Kermes vermilio and Kerria lacca). Previously, such dyes were only found in fabrics imported to the Nile Valley. In the 16th and 18th centuries, these dyes were also used by local dyers. This means that they had to learn this technology.’

Polish research in Old Dongola has been financed in recent years by grants from the European Research Council. Expedition leader, Dr. Artur Obłuski, received ERC Starting Grant and ERC Consolidator for this purpose.

This year's discovery of paintings from Old Dongola by the Woźniak UW expedition was among the 10 most important achievements in archaeology in 2023, selected by the prestigious American journal Archaeology. (PAP)

PAP - Science in Poland, Ewelina Krajczyńska-Wujec

ekr/ agt/ kap/

tr. RL