Dinosaurs could have used the feathers on their forelimbs and tails to rouse and chase their prey, suggest Professor Piotr Jabłoński and a team from Korea. To confirm this hypothesis, the researchers built a robot - Robopteryx that scares insects - and examined the neurons of grasshoppers.

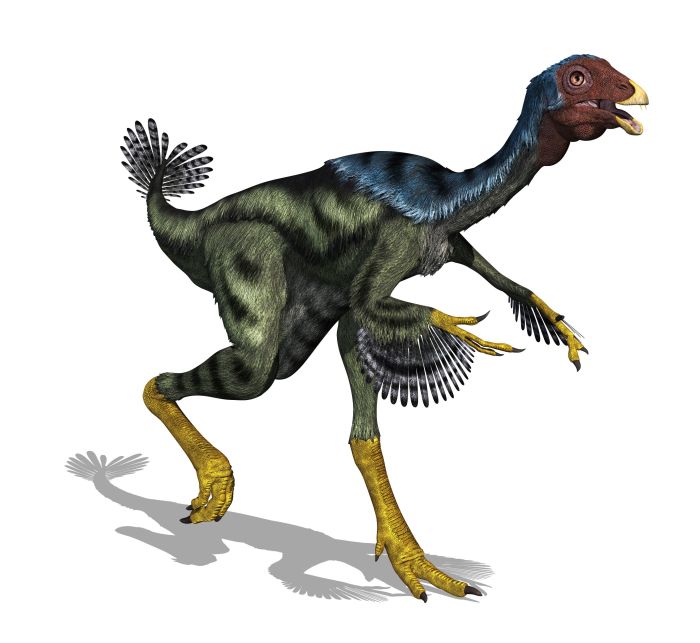

Birds are the closest modern relatives of dinosaurs. But where did their feathery wings come from? After all, they didn't grow them overnight... For some time now it has been assumed that the evolution of wings began with dinosaurs. We know that some of these ancient reptiles - for example Pennaraptors - while not yet able to fly, had stiff feathers on their tails and small wing-like feathers on their forelimbs (arms).

Feathers had to be promoted in evolution because dinosaurs needed them for something - even before they were able to lift the animal into the air. A new hypothesis is now presented in Scientific Reports by scientists from Korea and Professor Piotr Jabłoński, affiliated with the Museum and Institute of Zoology of the Polish Academy of Sciences.

The researchers show that dinosaurs may have used their forelimb and tail feathers to scare insects and flush them out of their hiding places.

BOO!

When a grasshopper sits quietly in the grass, it camouflages itself very well and is really hard to spot. It only becomes easy to track when it jumps. It turns out that feathers can be great for rousing prey.

When you wave something large near an insect, it may feel exposed and change its survival strategy: remaining still no longer makes sense and escaping seems to be a better choice. And during a chase, dinosaurs had a greater chance of winning against insects.

The researchers point out that some modern birds, such as the northern mockingbird, use this 'flush-pursuit' strategy. By rapidly displaying their wing or tail feathers, they rouse hidden insects and then chase them.

SCARY DINOBOT

The researchers decided to test this strategy in practice. They built a robotic dinosaur - 'Robopteryx', modelled on the dinosaur Caudipteryx - a small dinosaur that had feathers on its tail.

The robot was equipped with structures imitating feathers on its forelimbs and tail. It could rapidly display its plume. Researchers checked the effectiveness of such flushing of grasshoppers.

Grasshoppers were selected because they belong to the ancient class of springtails. It is therefore possible that the ancestors of grasshoppers coexisted on Earth with Pennaraptors.

WHAT SCARES THE GRASSHOPPER

The research showed that grasshoppers actually escaped much more often when the robot spread 'proto-wings' on its forelimbs than when it did not have them. Additionally, grasshoppers escaped more often when the 'proto-wings' had white spots, compared to when they were single-coloured. Additionally, grasshoppers were more likely to escape when tail feathers were present, especially when the tail feather area was large.

Professor Jabłoński and his colleagues first mentioned their 'flush-pursuit' hypothesis at a conference in 2005. Research on birds has shown that there are several species of birds that use their wings to hunt insects. These include slate-throated and rufous-crowned whitestarts, as well as the hooded warbler.

GRASSHOPPERS WATCH JURASSIC PARK

Professor Jabłoński also participated in the study of neurons of insects roused by birds. It turned out that insects have special neurons that are activated when they see the movement of a bird's plume. Jinseok Park - the first author of the paper - prepared computer animations of what dinosaurs displaying feathers might have looked like. And then he showed these videos to grasshoppers in the lab. The reaction of insect neurons to such an image was checked. ‘I used easily available inexpensive equipment to record responses of neurons,’ says Jinseok Park. The researchers found that neuronal responses, especially peak firing rates, were higher in response to animations with proto-wings than to those without them.

'Our work therefore proposes that relatively simple insect escape neurons shaped the evolution of feathers and +proto-wings+ in dinosaurs,’ says Jabłoński.

THE WORLD BELONGS TO THE PERSISTENT

Professor Jabłoński says that although he proposed the hypothesis about using wings for flushing prey almost 20 years ago, trying to get this idea recognized by others was a challenge. For years, he had been trying unsuccessfully to obtain funds for a scientific evaluation of this idea - in Poland, the USA and South Korea. 'Ultimately, the funding provided by Seoul National University allowed us to carry out joint research,’ the scientist says. However, there were problems with publishing the results. As many as 11 journals refused to accept the work with the research results for review. Persistence - and better documentation of the hypotheses - paid off. The results were published in the prestigious Scientific Reports.

FLUSHING OUT IS ONLY THE BEGINNING

Using feathers to rouse prey is just one of several elements of the team's hypothesis. The entire hunting process in the proposed manner requires an efficient pursuit of an escaping insect, and the feathers on the arms and tail could have helped in this at every stage. Professor Jabłoński tells PAP - Science in Poland that chasing prey may require quick turns, changes in speed, and high jumps.

'The feathers on the arms may also have served as an entomological net to catch insects, or simply to hit a flying insect to make it fall to the ground where a predator could more easily catch it. It is also possible that if, a predator chasing and attacking an insect had to jump down onto the insect (e.g. from a large stone onto the ground), the feathers on the arms and tail could act as a parachute. If the prey was large and fought when captured, the feathers on the arms may have helped immobilize the prey (e.g., by pressing the insect to the ground). All of these mechanisms have been previously proposed. The unique aspect of our hypothesis is that it integrates all the mechanisms related to hunting escaping insects and other prey,’ Jabłoński says.

He adds that in all these mechanisms, the larger the feather surfaces and the stronger the arm muscles, the greater the hunting efficiency. 'This would lead to the evolution of stronger muscles and larger +proto-wings+, which could have become the precursors of the muscular bird wings used in the active flight (not passive gliding flight) so characteristic of birds, says Jabłoński.

The research was prepared by a team of field biologists and integrative ecologists (Piotr G. Jabłoński, Sang-im Lee, Jinseok Park, Sang Yun Bang and Jungmoon Ha), palaeontologists (Yuong-Nam Lee and Minyoung Son) and robotic engineers (Hyungpil Moon and Jeongyeol Park).

PAP - Science in Poland, Ludwika Tomala

lt/ agt/ kap/

tr. RL