Bagaraatan ostromi was an enigmatic predatory dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous that had a complicated combination of features. New research conducted by palaeontologists, including researchers from the Polish Academy of Sciences, shows that the bones of two dinosaurs were mixed up in the skeleton, including bones from a juvenile tyrannosaurid.

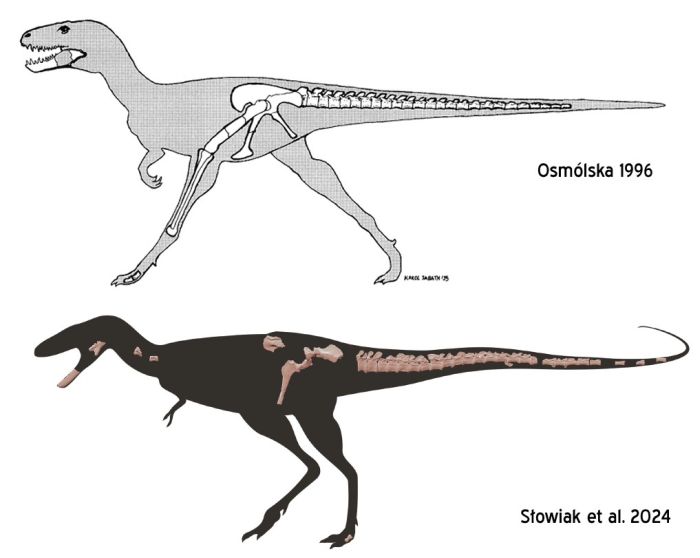

The source material consisted of fossils discovered in the 1970s in what is now Mongolia, described by Professor Halszka Osmólska in 1996. Bagaraatan ostromi was described on the basis of an incomplete skeleton that did not match any group of theropods (predatory dinosaurs) known at that time. Since then, it has been referred to in many scientific papers, but due to the complicated combination of features, there was still no consensus on what kind of dinosaur it was.

Dr. Justyna Słowiak and Dr. Tomasz Szczygielski from the Institute of Paleobiology of the Polish Academy of Sciences solved this puzzle in collaboration with Professor Stephen Brusatte from the University of Edinburgh.

'It turned out that, for unknown reasons, Professor Halszka Osmólska discarded some of the discovered bones during her research. Those bones led us to a new direction. Based on analyses and comparisons with other specimens from the Mongolian collection, we have shown that Bagaraatan ostromi was a combination of the bones of two dinosaurs. The leg bones belonged to an oviraptorosaur, probably an older specimen of the Elmisaurus rarus species, so they were unusually fused. This could have confused previous researchers,’ Dr. Słowiak tells Nauka w Polsce. Oviraptorosaurs are relatively small and slender predatory dinosaurs, more closely related to birds than to large apex carnivores.

The remaining fragments of the skeleton - the jaw and spine - turned out to belong to a juvenile tyrannosaurid, which lived 70 million years ago and was about 2-3 m long.

'It is one of the smallest juvenile tyrannosaurids currently known in the world. They are very rare, so each new one contributes a lot to the progress of knowledge about the development of tyrannosaurids in subsequent periods of life,’ says Dr. Słowiak.

Tyrannosaurids are a group of large apex predators that lived in North America and Asia during the Late Cretaceous (approximately 100–66 million years ago). This family includes the iconic T.rexes (Tyrannosaurus rex) and their Asian cousins: tarbosauruses (Tarbosaurus bataar). Dr. Słowiak deals with the latter in her research work.

It is still unclear whether Bagaraatan ostromi is a separate representative of tyrannosaurids or a juvenile Tarbosaurus or Alioramus. 'The skeleton is too incomplete to accurately determine its species, so we have not yet decided to assign it to any genus. Formally, the revised genus Bagaraatan remains valid, but only future discoveries will enable its full verification,’ Słowiak says.

Further details are available in the source paper published in the Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society.

When asked why it was previously believed that all these bones had to belong to one individual, Dr. Słowiak replies that bones found in one place are most often attributed to one dinosaur, although today palaeontologists are more cautious about this issue. 'Unfortunately, no photo of this specimen from the place of discovery has survived. We now know that there was a great diversity of dinosaurs in the Nemegt Formation in the Gobi Desert in Mongolia, and skeletal fragments can be mixed up or located so close to each other that a mistake may occur. Remember that the state of palaeontological knowledge has also improved significantly since the 1970s, not to mention the technological and methodological gap between those years and today,’ she says.

The scientist is now working on the description of individual development within the Tarbosaurus skull - she is preparing a virtual reconstruction with a description of the changes occurring in individual stages of the animal's life. (PAP)

PAP - Science in Poland, Agnieszka Kliks-Pudlik

akp/ bar/ kap/

tr. RL