Scientists at the University of Warsaw have discovered flatworms that spontaneously develop a second, fully formed head where a tail should have been, a phenomenon previously unknown in the animal kingdom. Despite the anomaly, the two-headed worms were able to feed and move, though movement was clumsy, researchers said.

“When we cut them in half, it turned out they could regenerate, and some of them reversed body axis, i.e., swapped front and back,” said Ludwik Gąsiorowski, PhD, from the Institute of Evolutionary Biology at the University of Warsaw, co-author of the study.

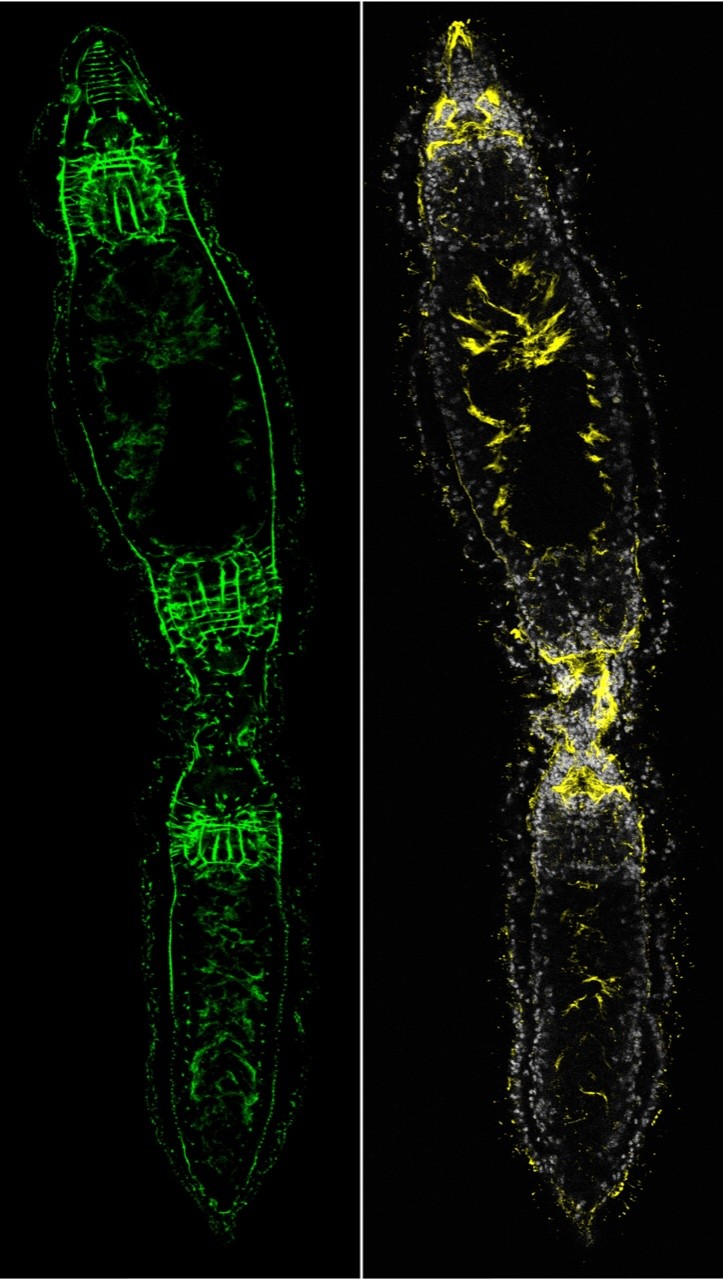

The phenomenon was first observed by Gąsiorowski’s doctoral candidate, Katarzyna Tratkiewicz, during routine observation of Stenostomum brevipharyngium cultures. “Some individuals clearly deviated from the norm. Where a tail should have been, a second head appeared. To our surprise, it was fully formed, including a throat and other properly functioning structures,” he said.

Further observations revealed that the anomaly was not isolated. Over several months, the culture maintained a population that included two-headed worms alongside normal individuals. This allowed detailed morphological and molecular analyses, resulting in a study published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences.

Flatworms of the genus Stenostomum are among the few animals capable of regenerating lost body parts and reproducing asexually.

“Stenostomum flatworms reproduce by a process called paratomy. During this process, the structures of the new individual begin to form in the central part of the adult worm's body. Unlike the typical budding process most of us are familiar with, the offspring doesn’t grow from the side of the body, but rather everything occurs along the same anterior-posterior axis. It is as if one body were slowly maturing in another,” Gąsiorowski said.

He added that the mechanism relies on precise molecular signaling. Stem cells differentiate according to gradients of morphogens, molecules that determine where the front and rear of the organism will develop.

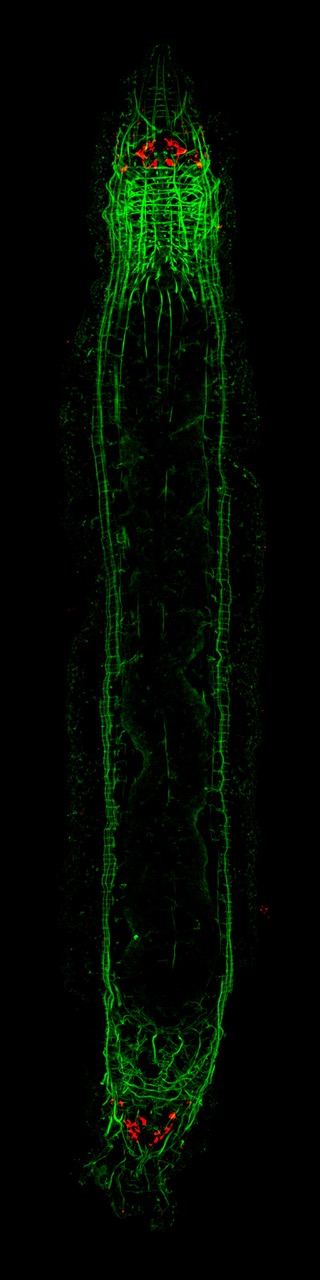

Normally, a new tail forms at the posterior end of the anterior segment, and a new head forms at the anterior end of the posterior segment. When development is complete, the two segments separate, becoming independent animals.

However, in the observed population, this process failed. “Instead of a new tail at the posterior end of the anterior segment, cells began to form another head. The adult individual thus became two-headed, but without a tail, while the hind worm continued to develop normally,” Gąsiorowski said.

The body of the worm resembled a chain of interconnected segments: normal head-thorax-inverted head-normal head-thorax-tail. When the new individual matured, it separated and lived independently, leaving the parent worm two-headed.

Despite lacking a hind gut and an excretory opening, the worms were able to feed and digest normally. Movement was impaired because each head responded independently to stimuli.

The researchers tested regeneration by cutting the atypical worms. “Both heads had regrown their missing tails. Interestingly, in the fragments with the inverted head, an inverted body axis was established after regeneration, meaning that a new tail grew on the anterior side,” Gąsiorowski said.

“This means that what was previously the front of the worm became its rear. This phenomenon is unprecedented in animals, because body orientation is usually established once, during embryonic development, and remains constant throughout life,” he added.

The anomalies persisted in the culture for two months before spontaneously ceasing. Researchers considered possible causes, from genetic mutations to environmental factors. “A developmental error therefore seems most likely. Some stem cells may have erroneously responded to the morphogen gradient, resulting, for example, from mutations at the single-cell level,” Gąsiorowski said.

He added that in similar cases from 90 years ago, other Stenostomum species exhibited deformities associated with aging, but those individuals died. “Two-headed individuals can also be obtained in planarians through manipulation of gene expression. However, the spontaneous development and stable inversion of the body axis, as in Stenostomum brevipharyngium from the University of Warsaw, is a previously unknown phenomenon,” he said.

It is unclear whether such anomalies occur in flatworms in the wild. “These are very small animals, difficult to observe, and often overlooked in research. Moreover, in the wild, individuals with such a deformity would likely be quickly eliminated due to difficulties with movement, obtaining food, and avoiding predators,” Gąsiorowski said.

He added: “Such a profound remodelling of the body plan, without loss of vital functions, demonstrates how flexible even the simplest life forms can be.”

The researchers continue to study gene activation during paratomy and aim to test whether manipulating the expression of selected genes can control head or tail development.

Gąsiorowski added that understanding how cells recognize the head/tail direction in simple flatworms could contribute to understanding regenerative processes in more complex animals.

PAP - Science in Poland, Katarzyna Czechowicz (PAP)

kap/ agt/ ktl/

tr. RL