Archaeologists have discovered lumps of intensely red cinnabar in the graves of women buried 2,000 years ago at the Chervony Mayak cemetery in southern Ukraine, suggesting that Late Scythian communities may have used the toxic pigment to slow decomposition or neutralize microbes.

The Chervony Mayak cemetery, located on the right bank of the Dnieper in Kherson Oblast, was part of a Late Scythian culture that thrived from the 2nd century BCE to the mid-3rd century CE.

Members of the culture practiced skeletal burial rites in pit, niche, and catacomb graves. Mass burials were common; some graves contained up to a dozen stacked bodies, while one discovered on the Crimean Peninsula held at least 125 individuals.

The cemetery was first explored in 1975. Since then, research by multiple institutions has uncovered 177 graves. In three of these, a team from the Institute of Archaeology of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine in Kyiv, led by Professor Oleksandr Symonenko, identified vivid red lumps.

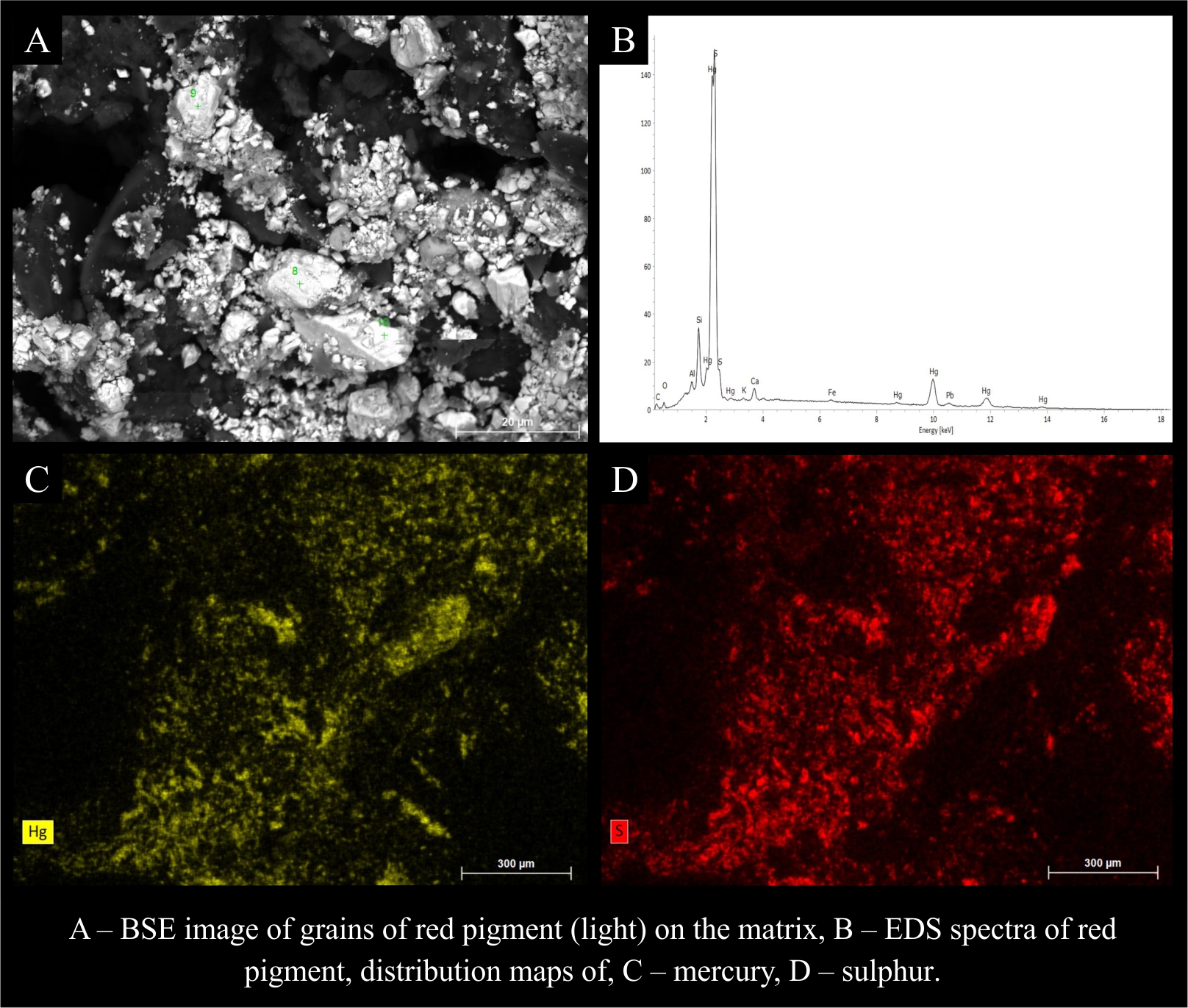

Analyses conducted with researchers from Maria Curie-Skłodowska University, Jagiellonian University, and the University of Warsaw, published in Antiquity, confirmed that the pigment is cinnabar—a mercury sulphide known for its intense red hue and toxic properties. This marks the first documented case of cinnabar use by the Late Scythian culture confirmed by archaeometric research.

“Pigments of various shades of red have been discovered in graves attributed to the Late Scythian culture, but they are rarely subjected to archaeometric analysis using specialized equipment. We were very fortunate to have assembled an international team with the appropriate samples for analysis, the appropriate equipment, and the necessary knowledge,” said Beata Polit, PhD, from Maria Curie-Skłodowska University.

The burial chamber contained two women, one aged 18–20 and the other 35–45. Three lumps of cinnabar were found near the skull and upper chest of the older woman. Fragments of a vessel, bronze earrings, and beads date the grave to the 1st century to the first half of the 2nd century CE.

Polit noted that the women were buried within a short time span, adding that the body of the first buried woman was moved from the entrance toward the wall of the burial chamber. The lumps of cinnabar found near her were small and their location near the skull and ribs was very common, suggesting that red pigment served a specific function in funerary rituals.

While the exact purpose of cinnabar in Late Scythian graves remains uncertain, archaeologists believe its placement was deliberate. Sulphide-containing pigments may have acted as antibacterial agents.

“In order to bury another deceased person, the grave had to be opened, and the burial chamber undoubtedly contained various microbes, some of them very harmful. This was accompanied by a strong, unpleasant odour. It is possible that, in the context of graves to which more bodies were added, the pigment could have been used to neutralize bacteria or slow down the decomposition of the body. This, of course, is just one hypothesis,” Polit said.

She added that in some graves, the limited number of pigment lumps could indicate symbolic or protective use. “Pigments sometimes found in containers or shells may have served as cosmetics or paint ingredients. People of that time certainly realized, intuitively or based on experience, that certain minerals, plants and other substances could be harmful to the body, but I do not think they had scientific knowledge of their toxicity,” Polit explained.

PAP - Science in Poland, Ewelina Krajczyńska-Wujec

ekr/ agt/

tr. RL