Some carbonated drinks, including cola drinks, contain phosphoric acid which can put consumers at risk of developing infectious urinary stones, Polish researchers believe.

A paper on this subject, written under the supervision of Professor Jolanta Prywer from the Institute of Physics of the Lodz University of Technology, appeared

Writing in the journal Scientific Reports, researchers under the supervision of Professor Jolanta Prywer from the Institute of Physics of the Lodz University of Technology found that phosphoric acid may also cause faster growth of urinary stone layers in people who already have a stone unrelated to a bacterial infection in their urinary tract.

Urolithiasis - a disease that affects 1 to 20 percent of the population - is a crystallopathy where a solid piece of material develops in the urinary tract. There are several types of urinary stones (also called kidney stones) with different structures and pathogenesis. The most common are urinary stones made of calcium oxalate. The main reasons for their formation are metabolic disorders, which usually react to treatment quite well.

Professor Prywer said: “These are infectious urinary stones, the formation of which is associated with urinary tract infection caused by urease-producing microorganisms.”

According to the researcher, in recent years there has been a strong increase in the incidence of infectious urolithiasis, especially in highly developed countries.

To find out why, Prywer and her team focused on phosphoric acid found in some non-alcoholic carbonated drinks (especially cola drinks). Phosphoric acid is used as a preservative and a substance that gives a sour taste.

The researchers wondered whether consuming drinks containing phosphoric acid could be a risk factor for developing infectious urolithiasis.

Professor Prywer said: “Infectious urinary stones are a much more difficult problem than metabolic stones. The commonly used crushing of infectious stones in the urinary system - for example with ultrasounds - is not a complete cure, because it does not eliminate the causes of urinary stones' formation. In the case of such stones, it is not enough to eliminate the infection itself either.

“This is because microorganisms can survive in an already formed stone, building themselves into its structure. When the stones are crushed, for example with high-energy ultrasonic waves, microorganisms are released into the urinary tract, which causes a relapse after treatment in up to 60 percent of cases.

'In the case of untreated urinary tract infection, infectious stones grow very fast, filling the pelvis and renal cups. The formation of clinically significant infectious urinary stones takes from four to six weeks. Leaving such stones without treatment can lead to kidney loss in 50 percent of cases, and in 25 percent of cases even to death in five years.”

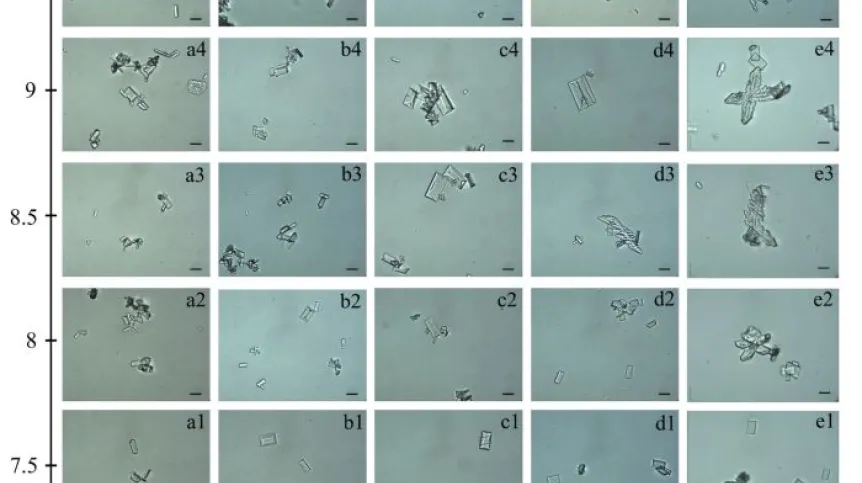

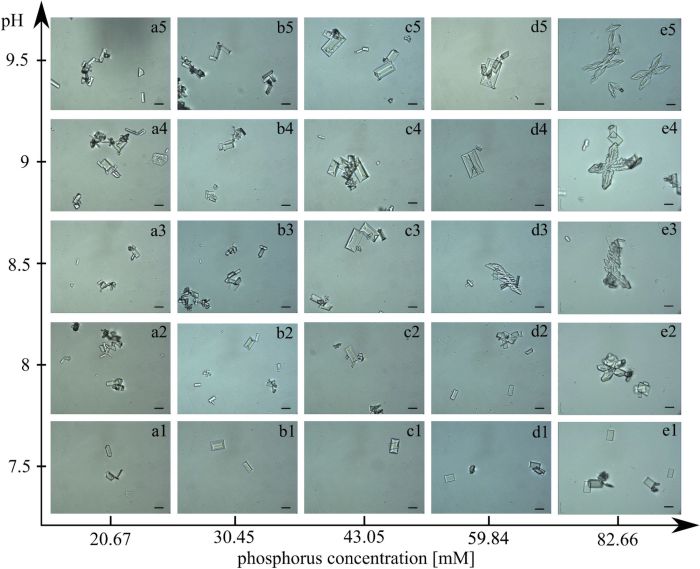

She continued: “In the paper in Scientific Reports we discuss the effects of phosphoric acid on the crystallization of struvite crystals, which are the main component of infectious urinary stones.”

Struvite crystals can grow in the urinary tract under the influence of urease-producing bacteria. Urease (a bacterial enzyme) breaks down the urea present in the urine of a healthy person, initiating a cascade of chemical reactions leading to struvite crystallization and the formation of other components of infectious urinary stones.

The experimental system used in the study reproduces the conditions naturally occurring in the human body during the infection with bacteria of the genus Proteus. In this model, the experiment is carried out at 37 degrees Celsius in an artificial urine environment, in which the mineral content corresponds to the daily concentration in the urine of a healthy person.

As part of the experiment, four phosphoric acid concentrations were examined. Phosphoric acid at a high concentration reduces urine pH to a deadly level for bacteria. Under these conditions, bacteria would not be able to cause struvite crystallization and thus the formation of urinary stones. That would be good news for people who like bubbles. However, researchers doubts whether their system - studied in laboratory conditions - can be reproduced in a living organism with a constant urine flow. According to them, it would be difficult to maintain such a low pH of urine.

According to Professor Prywer other scenarios are more likely, in which phosphoric acid in urine is lower and does not reduce urine pH to bactericidal level. She said: “And if we have a urine pH that is not bactericidal, the higher the concentration of phosphoric acid, the earlier the process of struvite crystallization begins, which of course is not a beneficial effect.”

The research results also show that the amount of crystallizing struvite slightly increases as phosphoric acid concentration increases. In addition, in the presence of phosphoric acid, especially for the higher - although still not bactericidal - concentrations of this acid, struvite crystals form as large dendrites. And this is not a beneficial effect, because they can damage the urinary tract epithelium die to their irregular shapes and sharp edges.

All these effects of phosphoric acid are possible in the case of urinary tract infection with urease-positive bacteria.

When such bacteria are not present in the urinary tract, phosphoric acid no longer causes struvite crystallization. However, another problem is what happens when the patient already has a urinary stone made of, for example, calcium oxalate crystals, unrelated to urinary tract infection with urease-positive bacteria.

Prywer said: “In this case, in the context of the research presented in our paper, the formation and growth of an urinary stone would be influenced by three factors: urinary tract infection, increased levels of phosphorus acid in urine and the presence of urinary stone.”

She added that in such a situation it is very likely that due to the presence of phosphoric acid, the existing urinary stone may grow faster. This is due to the fact that the urinary stone surface is usually porous, which promotes the adhesion of bacteria, which can become centres of subsequent urinary stone layers.

“Generally, it can be said that consuming drinks rich in phosphoric acid can be a risk factor for developing infectious urinary stones, and in the case of a patient with a non-infective stone in the urinary tract, phosphoric acid may cause faster growth of subsequent layers of this stone,” she said.

PAP - Science in Poland, Ludwika Tomala

lt/ zan/ kap/

tr. RL