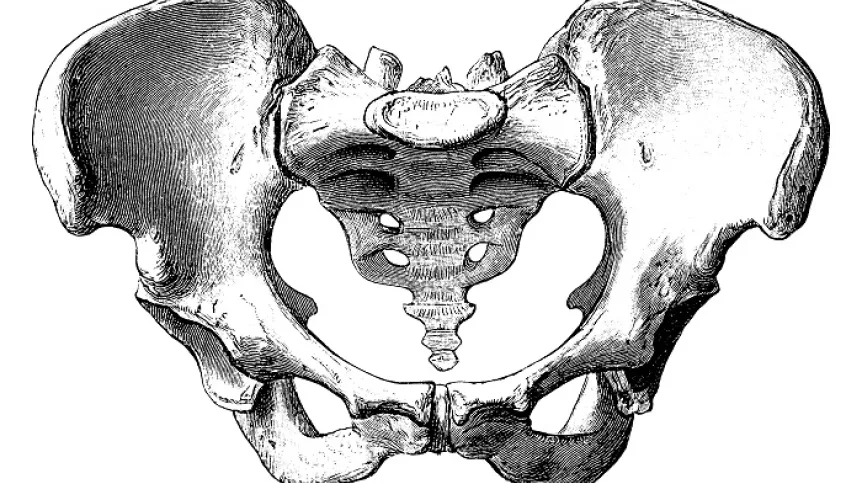

The pelvis in women and men is a more plastic part of the skeleton than previously thought: it can change under the influence of certain factors, according to research by Dr. Anna Maria Kubicka from the Poznań University of Life Sciences. She has also determined that subsequent pregnancies do not leave permanent changes in the pelvic morphology in women. She presented the results of her research in Scientific Reports.

'Previous studies assume that the structure of the pelvis is under strong adaptive pressure due to two phenomena: adaptation to human bipedalism and giving birth to newborns with a large head circumference. Therefore, it was thought that a skeletal element under such strong pressure could not be characterized by plasticity, or susceptibility to changes in structure during life. The main aim of the research was to check whether - and to what extent - the pelvis can change shape under the influence of external factors. In the case of new analyses this external factor was body weight, specifically the BMI index, which allows to determine whether a person shows a deviation from the normal weight in relation to their height,’ says Dr. Kubicka.

To determine the level of pelvic plasticity, the scientist used the information available in the New Mexico Decedent Image Database, which contains whole body CT scans performed on people who died in the state of New Mexico between 2010 and 2017. The study included scans and biological data on over 300 people aged 1 to 80.

Dr. Kubicka calculated the body mass index (BMI) for the examined people, and then, based on CT scans, she created 3D models of their pelvises. She analysed the changes in the structure not with traditional measurements, but with geometric morphometry - a method that comprehensively examines changes in the shape of the studied object.

The researcher emphasizes that the pelvis is an important part of the human skeleton in the context of research on adaptation to bipedalism or adaptation to childbirth. 'Previous studies have assumed that this part of the skeleton is non-plastic and conservative, and its structure is generally not susceptible to change. Studies that used body mass index or the number of pregnancies allowed us to verify earlier assumptions', Dr. Kubicka says.

The scientist emphasises that so far testing various hypotheses on osteological collections (specialized collections of bones) has been limited. One of the reasons is that such collections rarely include children's bone material. Calculation of BMI for a given person based on their skeleton is also subject to error due to the fact that the body weight and height of a given individual are values obtained based on formulas that have their own specific error range. Therefore, the American database, containing numerous CT scans along with biological and demographic data, tests many interesting research questions.

Kubicka ultimately determined the plasticity of the pelvis was high - which means that its shape could change. In the case of women and men, however, this applies to different developmental stages. In women during puberty, the BMI category (in practice, underweight, normal weight, overweight or obesity) programs the development of the pelvic structure - which means that underweight people usually have a different shape of the pelvis than, for example, overweight people.

Interestingly, the pelvis in women loses its susceptibility to changes after the age of 25, the researcher notes. In her opinion, this is associated with the adaptation of the skeleton to childbirth: the pelvis must support the abdominal and pelvic organs and the foetus during pregnancy. Hence, its susceptibility to shape changes after the end of skeletal development is lower.

Kubicka observed the opposite tendency in men. During childhood, BMI has no effect on their pelvis, but after the age of 25, overweight or obesity in a given man significantly affects its anatomy, especially the position of the pelvic plates, the subpubic angle and the posterior position of acetabulum.

Kubicka also studied the possible relationship between the number of pregnancies and the shape of the pelvis in women between 25 and 45 years of age. 'The number of births was not reflected in the permanent changes in the shape of the pelvis in women - which shows that despite the increased mobility of the pubic symphysis during pregnancy, the pelvis returns to its original shape after childbirth. This was partly indicated by earlier results of other researchers,’ says Kubicka, who confirmed it in a larger number of women.

'The obtained results are interesting because they show how our bones can change during life, and when they are most susceptible to modelling. Interestingly, the period of the greatest possibility of morphology changes is different in women and men, she adds. ‘The study of 3D models shows that the pelvis - despite previous assumptions - is a fairly plastic part of the postcranial skeleton. However, it should be emphasised that these changes in its shape include anatomical areas that are not strictly related to adaptation to childbirth (i.e. pelvic inlet and outlet). At the same time, this proves that the pelvis is very conservative in structure in certain areas, especially in women, Dr. Kubicka says.

More information: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-023-36703-2

PAP - Science in Poland

zan/ kap/

tr. RL