Negative stereotypes about women in science make themselves felt in non-obvious ways.

Presenting women who have achieved something important in a given field of science sometimes makes people consider this field to be less attractive, research conducted in Poland shows.

Scientists investigating negative stereotypes about women in science have called this ‘non-obvious’ discrimination the reverse Matilda effect.

'The Matilda effect consists of ignoring or downplaying women's contributions to science due to the assumption that only men can make significant contributions. However, this false assumption also leads to less obvious consequences. Some people may conclude that if women achieve success in a certain field of science, it means that this field is not difficult or interesting. We called this effect the reverse Matilda effect', Dr. Wojciech Małecki from the University of Wrocław, team leader and one of the authors of the publication in Science Education says.

Dr. Marta Kowal, a psychologist from the University of Wrocław, who also participated in the research project, adds: 'The results of our research are fascinating and at the same time disturbing. On the one hand, we see how strong the stereotypes about the role of women in science are, and on the other hand, how some attempts to counteract these stereotypes can bring the opposite effect'.

In Poland and in the world, we have an underrepresentation of women (they are disproportionately underrepresented) in science, technology and mathematics (STEM). There are also fewer women authors of prestigious scientific publications.

'An explanation may be prejudice against women in STEM, for example the stereotype that women are less suitable for doing science than men. The consensus is that prejudices should be counteracted because they may cause women's achievements to be assessed worse than men's achievements in an unjustified way. Aware of such stereotypes, some women may in turn be less confident about their skills or that they will be appreciated, which makes it more difficult for them to pursue a career in an environment where the majority are men', says Małecki. The researcher deals with the impact of various narratives - literary and journalistic ones - on the attitudes of recipients.

MATILDA EFFECT

Modern research shows that reviewers still evaluate the same scientific work better if it is signed by a man rather than a woman. Scientific papers by women are also statistically less frequently cited, and women less frequently receive scientific awards (https://doi.org/10.1177/0306312711435830). The Wrocław scientists decided to investigate ways of combatting prejudice more effectively.

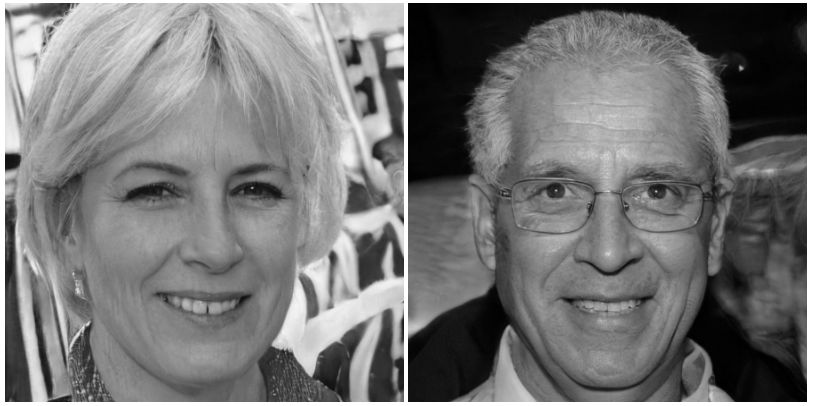

The scientists showed over 800 high school students one of several versions of a presentation about STEM, biology and mathematics, which concerned interesting discoveries in these fields. The presentations differed only in the gender of the scientists to whom particular discoveries were attributed. In one version, discoveries in a given field were attributed to men (e.g., Professor Patrick Coleman, invented for the purpose of the study), in the second version, they were attributed to women (e.g., the fictional Patricia Coleman), and in the third, controlled version, the authorship was not specified. Presentations in which women appeared made male and female students assess a given field as less interesting and express less willingness to study it.

It seemed that the version with female scientists would be more motivating for girls and would not negatively affect the boys' assessment. 'We assumed - in accordance with one of the psychological theories - that if the presentation matches the gender of the presented scientists with the gender of the respondents, it should increase the motivation of the female study participants to study a given field. And the result was completely different', says Dr. Małecki.

Seeing that women had achieved success in a given field, girls did not feel encouraged to become interested in it. Their reaction was quite the opposite: versions of presentations with female scientists made students (regardless of gender) consider the field of knowledge shown in the presentation to be less interesting.

WRONG ASSUMPTIONS

The researcher explains which cognitive mechanisms could be behind this result. If deeply rooted stereotypes suggest that women are less suitable for science than men, or not suitable at all, and women have made important achievements in a given field, a person who believes in such stereotypes may conclude that the entire field is not valuable or worthy of interest, Małecki says.

Dr. Kowal adds: 'Stereotypes can be characterized in two dimensions - warmth and competence. Men are identified with a high dimension of competence, and women with a high dimension of warmth. So if a woman achieves success in some field, it can cause cognitive dissonance'. Cognitive dissonance is the unpleasant feeling of discomfort we feel when a contradiction creeps into our beliefs and values. And this discomfort may have arisen when subjects living with the prejudice that 'men are competent, not women' heard about a successful (i.e. highly competent) female scientist. 'To eliminate this unpleasant state of dissonance, the simplest solution is to recognise that a given gender in the field is not important or noteworthy at all', adds the researcher.

When asked whether the reverse Matilda effect can be observed in other spheres of life, Małecki says that, for example, this result is consistent with the relationship between wages and the feminisation of professions. 'Research shows that with the feminisation of professions, wages decrease. Perhaps this process is also influenced by stereotypes related to what women are +fit+ for', says Małecki. He also mentions the book market: he cites research showing that the average price of books written by women is 45% lower than the average price of books written by men, although this is not due to objective factors, such as differences in the genres preferred by women writers.

According to the researcher, the way to weaken the Matilda effect is to prevent the spread of stereotypes. 'We acquire such prejudices during the socialisation stage. We learn about social gender roles from an early age', Malecki says. Therefore, it is best to ensure that children encounter talented male scientists as well as female scientists in books, films and the media. Various messages should present scientists from different demographic groups and different fields of science. The stereotypical figure of a scientist as a white, scatterbrained, elderly man in a white coat - associated with Einstein - needs to be abandoned.

DISTANT AND CLOSE WOMEN

The researcher emphasises that the conclusions from this research (discouragement from a given field due to the presentation of women's success in this field) cannot be extended to other ways of popularising research work - e.g. direct contact of students or researchers with children or young people.

Wojciech Małecki emphasises that the research he and his team conducted have their limitations. 'In our presentations, we talked about prominent middle-aged female scientists from other countries', he says. And this could have increased the audience's distance from these characters. It is therefore possible that, instead of identifying with other successful women, the girls focused on the differences - the fact that this was a distant, outstanding scientist from the USA or the UK. If the message were worded slightly differently - and talked about young Polish women scientists - it would be possible to build greater recipients' acceptance towards the presented research.

'Further research is needed to explain the effective mechanisms behind these stereotypes to better understand how to counterbalance them and open the door to careers in science for women. We still have a long way to go, but I believe it is worth pursuing', adds Kowal.

In addition to Marta Kowal and Wojciech Małecki, the team also included Professor Chip Bruce (University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign), Dr. Anna Krasnodębska (WSB Merito University Opole) and Dr. Piotr Sorokowski, a professor at the University of Wrocław. (PAP)

PAP - Science in Poland, Ludwika Tomala

lt/ bar/ kap/

tr. RL