Scientists at the University of Warsaw have analysed unusual cavities preserved on the shells of sea turtles that lived 150 million years ago, concluding that the marks record ancient interactions with parasites, symbionts and predators.

The findings, published in Lethaia, suggest that the shells preserve evidence of long-term ecological relationships in Jurassic marine ecosystems.

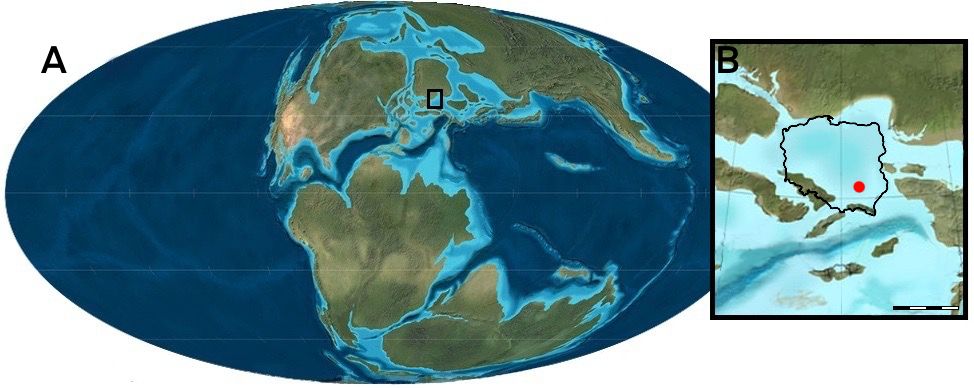

The fossils come from Upper Jurassic deposits at Krzyżanowice, on the northeastern margin of the Świętokrzyskie Mountains. The shells belonged to primitive sea turtles that inhabited a shallow sea covering the region during the Late Jurassic.

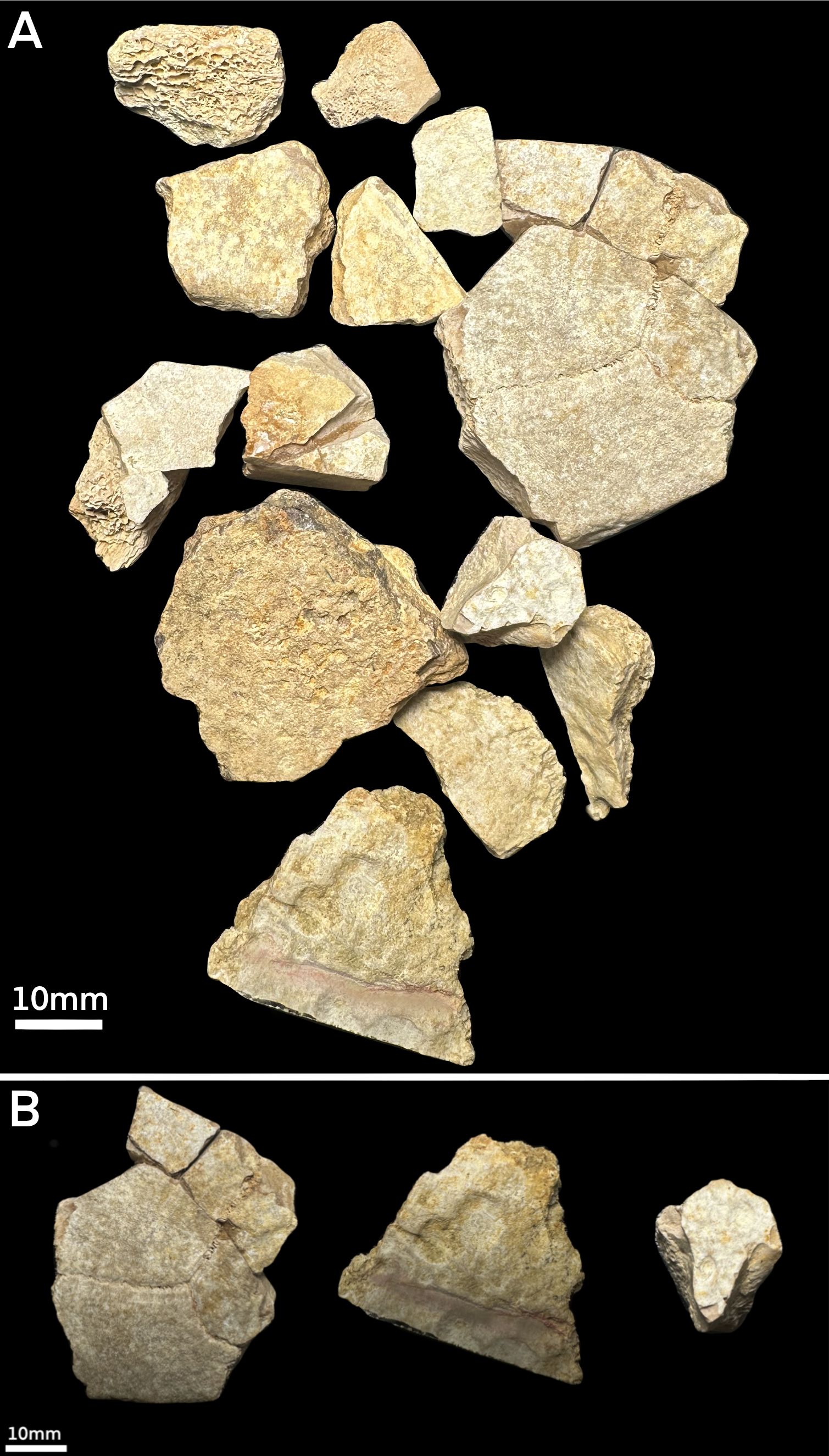

“Unique fragments of turtle shells have been preserved in calcium carbonate rocks. Their surface contains numerous depressions, the formation of which has been a mystery until now. We decided to solve this mystery. To this end, we cut selected plates from the turtle shells into thin slices and then created slides that could later be viewed under a microscope. Each cross-section of the shell ran through the mysterious depressions,” says project leader Daniel Tyborowski, PhD.

He goes on to say that some of the cavities showed internal growth of fresh bone. “These are traces of shell regeneration, that is, its reconstruction after something caused a fragment of tissue to be removed. The fact that shell regeneration occurred proves that the mysterious depressions were created while the turtles were alive, not after their death. The mysterious marks were likely created by various marine invertebrates that lived on the turtles’ shells,” he says.

Tyborowski adds that fossil turtle shells often bear signs of bioerosion, which may be produced by symbionts, parasites or predators. He says these traces can be used to reconstruct ecological dynamics over geological time.

“By looking at what made the marks on turtle shells during different geological periods, we can infer what types of interactions between organisms dominated marine ecosystems. We have termed this method the +ecological island concept+. It states that traces of symbiotic or parasitic invertebrates, such as polychaetes, bivalves, and sea urchins dominate on the shells of sea turtles from the Jurassic (201–143 million years ago). However, traces of predators, such as marine reptiles are more common on the shells of turtles from the Cretaceous (143–66 million years ago). Only after the Cretaceous–Palaeogene extinction (66 million years ago) did an ecological balance between symbionts, parasites, and predators occur in the turtle shell record. Turtle shells are therefore an excellent source of information on changes occurring in marine ecosystems, particularly in the midwater zone,” he says.

The study was conducted by Tyborowski and Gabriela Sienkiewicz from the University of Warsaw’s Faculty of Geology.

The full text of the publication is available here. (PAP)

PAP - Science in Poland

akp/ agt/

tr. RL