Agricultural reforms introduced in early medieval Europe sharply increased biodiversity in parts of Germany and pushed species richness to levels higher than before human settlement, according to a study published in PNAS. The findings challenge the assumption that agriculture has historically harmed ecosystems, co-author Professor Adam Izdebski said.

He told the Polish Press Agency (PAP): “We decided to investigate how far back in time the current biodiversity crisis stretches. We expected to find that the problem grew with the development of agriculture and occurred well before the Industrial Revolution. But our research led to a completely different conclusion: we show that for hundreds of years in the history of our European culture, humans could have been a very positive force for the natural environment.”

He added that for centuries Europe used land-management systems that preserved or rebuilt species richness. “Human pressure does not have to be negative; it is part of nature. We should not treat ourselves as pests,” he said.

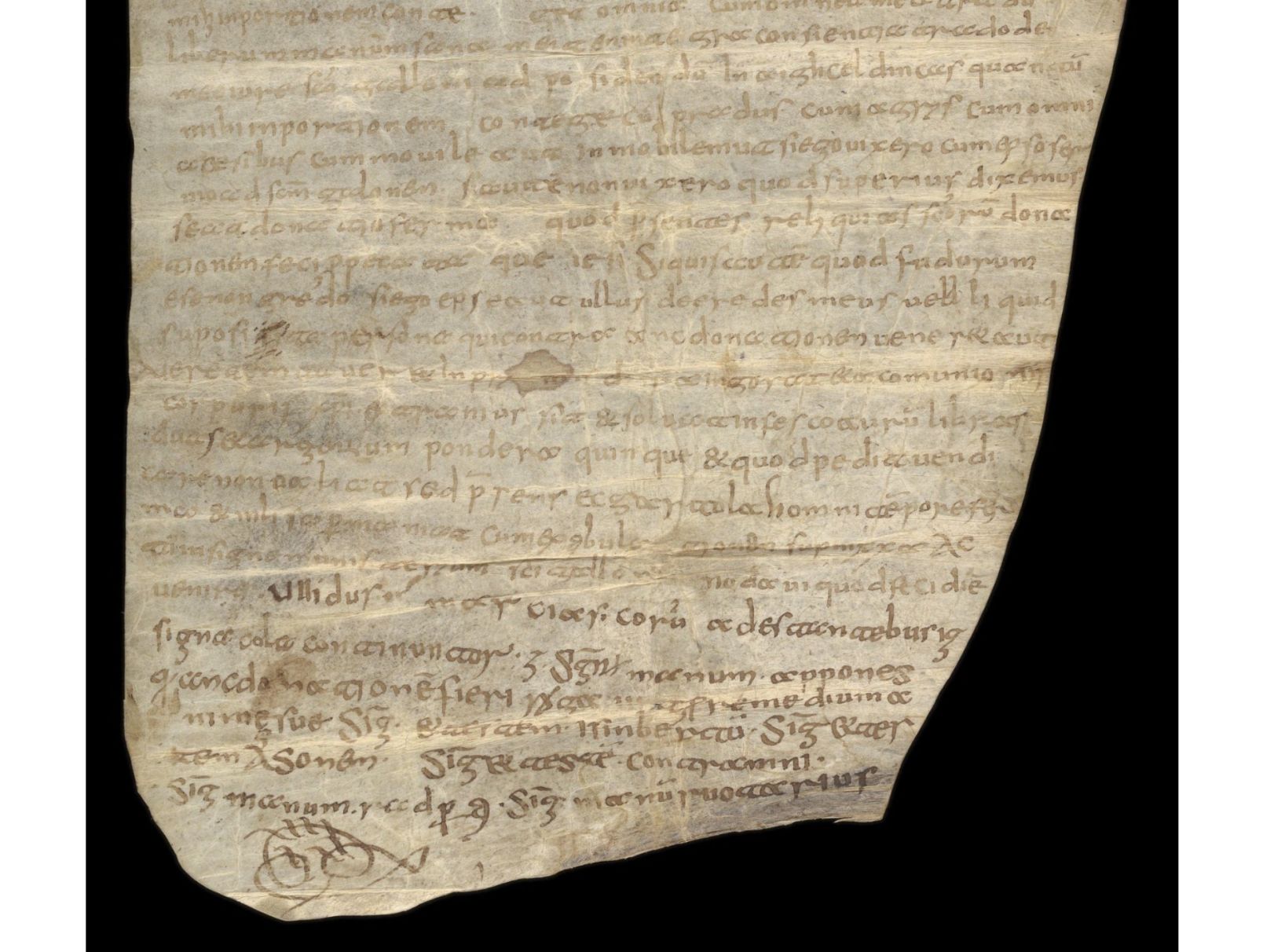

The research team combined palaeoecology, archaeobotany and historical analysis to study soil cores taken around Lake Constance in southwestern Germany. They examined pollen deposited over thousands of years and compared it with written records from nearby early medieval centres, including the St. Gallen monastery, whose eighth-century archive documents the spread of new agricultural practices.

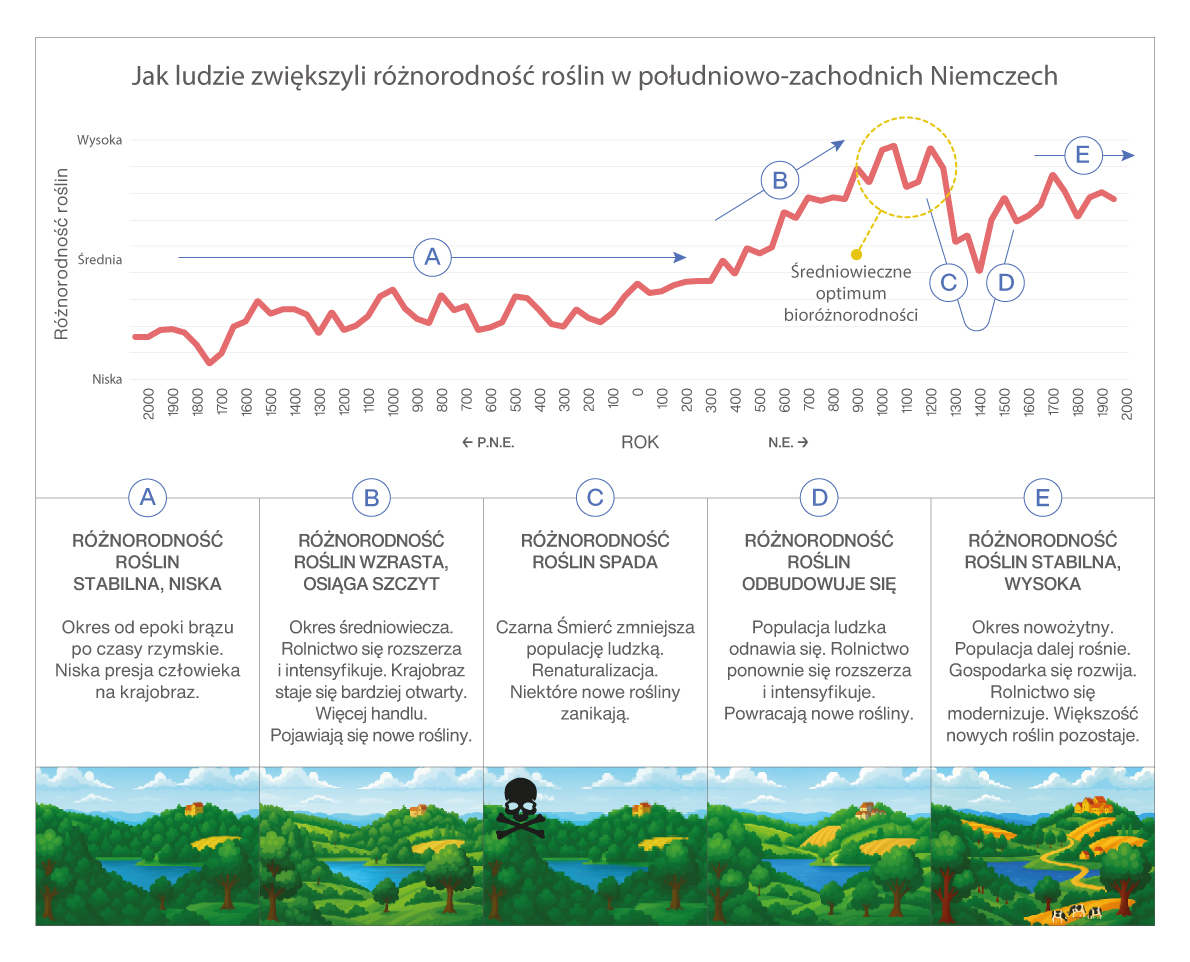

According to the study, the highest biodiversity in the last 4,000 years occurred not during periods of minimal human activity but after early medieval agricultural innovations. Plant diversity in the region rose markedly between 500 and 1000 CE.

A decline followed the Black Death in the mid-14th century. With populations collapsing, sometimes by half, farmland reverted to unmanaged vegetation. The shift reduced biodiversity, and the region never returned to its pre-1350 levels.

The team selected Baden-Württemberg as the best location for reconstructing the history of biodiversity in Europe. Izdebski said the turning point was the “Carolingian Green Revolution,” an agricultural package introduced under Charlemagne and earlier, later reaching Poland in the 12th and 13th centuries.

Central to this package was the three-field system, in which land was divided into spring crops, winter crops and pasture.

“Compared to the simpler system of rotational cultivation and fallowing, the Carolingian economy created a greater mosaic and diversity of land uses, as well as a greater diversity of plants, and consequently, animals, birds, and insects,” Izdebski said.

The system continually reshuffled land use and encouraged field margins that hosted wildlife.

Other changes included widespread use of horses for traction, improved ploughs and tools, and cover crops planted after harvest to maintain soil fertility. Farmers operated within monastic, royal or aristocratic estates that pushed for higher yields, drawing agriculture into networks of innovation and early markets.

Forestry diversified as well, including managed woodlands for grazing and firewood and the pollarding of trees to produce annual branches.

Plant dispersal also shifted. Weeds important for biodiversity travelled with cereal seeds. “For example, cornflower, a blue wildflower, arrived in Europe with Carolingian agriculture and signals the introduction of this package. This annual plant copes well with deeper ploughing and rye cultivation,” Izdebski said.

Another sustained decline in biodiversity appeared with the Industrial Revolution in the late 19th century. Regional specialization in agriculture expanded, machinery demanded uniform landscapes, railways and growing cities increased food production pressures, and artificial fertilizers spread after World War I. Organic farming emerged in Germany in the 1920s as a reaction to industrialized methods.

Izdebski said restoring a “pre-human” environment is not realistic. “You might think that a return to pre-human state, to the previous interglacial period or even earlier, 30,000 years ago, would be ideal for the environment. But then we would also have to introduce aurochs, elephants, and rhinos – large animals that devoured the forest. And that is unrealistic.”

He added that medieval landscapes functioned similarly to ancient ecosystems shaped by large herbivores.

“I think the conclusion is that farmers have a very positive task to perform, one that is both necessary and realistic. It is possible to conduct productive agriculture that simultaneously maintains a diverse landscape. This is precisely what some contemporary programmes, such as the Green Deal or the great programme to create an ecological civilization in China, are trying to achieve, for better or worse,” he said.

PAP - Science in Poland, Ludwika Tomala (PAP)

lt/ bar/ lm/

tr. RL