Ultraviolet radiation is present around some of the youngest known stars, even before thermonuclear fusion begins in their cores, according to new observations from the James Webb Space Telescope.

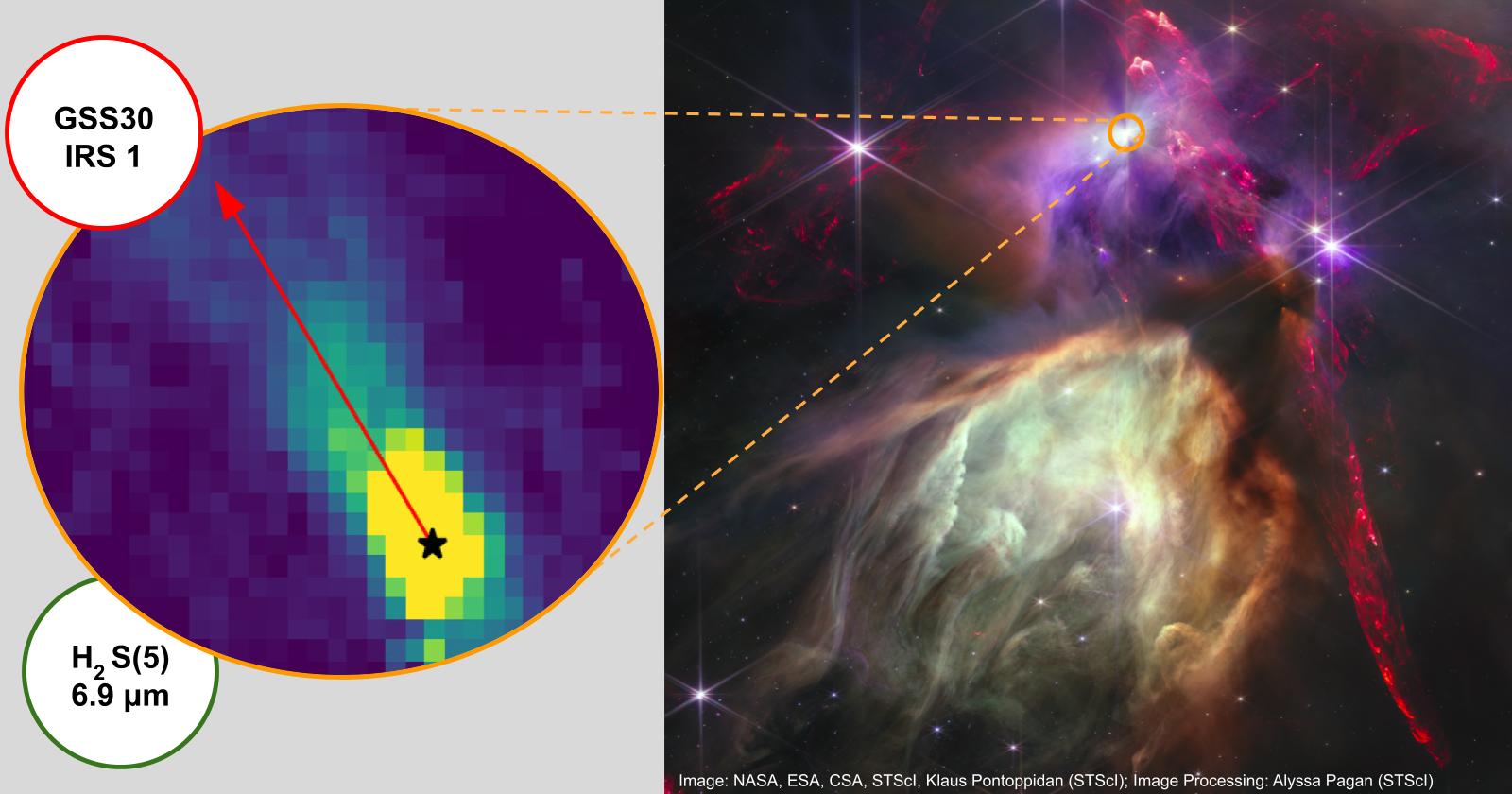

An international team of researchers from the United States, Poland and Germany has found evidence of locally produced ultraviolet radiation around five protostars forming in a dense molecular cloud in the constellation Ophiuchus.

The objects are less than 500,000 years old and are still in the earliest stages of stellar formation.

The findings published in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics were led by Agata Karska of Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń and Iason Skretas of the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy. The researchers focused on protostars expected to evolve into Sun-like stars.

“In the future, the protostars we studied will become stars very similar to our Sun. This is the most common type of star in galaxies,” Karska said.

Ultraviolet radiation is known to influence chemical reactions and heating processes in gas surrounding mature stars, including the Sun. Until now, however, its role during the earliest phases of star formation has been difficult to confirm observationally.

According to the researchers, the presence of UV radiation at this stage has important implications for how stars and planetary systems develop.

Ultraviolet light alters the temperature and chemistry of surrounding gas, which later forms a protoplanetary disk and, eventually, planets.

HOW TO STUDY LIGHT IN THE DARK

Karska said UV radiation changes the conditions under which a star forms by affecting how gas heats and which chemical reactions can occur. As a result, she said, models of star and planet formation need to account for UV radiation earlier than is often assumed.

Protostars form inside cold molecular clouds composed of gas and dust. As material falls inward under gravity, the growing object accumulates mass. Because angular momentum must be conserved, not all of the infalling material can reach the center. Some of it is redirected and expelled at high speeds in two opposite directions, forming bipolar jets.

When these jets collide with surrounding gas, they create shock waves. The shock-heated gas can emit radiation, including ultraviolet light, even before nuclear fusion begins in the protostar’s core.

Directly observing ultraviolet radiation from protostars is not possible because dust in star-forming regions blocks high-frequency radiation. These regions appear as dark patches in visible and ultraviolet light.

Karska compared the effect of the dust to cigarette smoke. The dust consists of silicate or carbon particles suspended in gas, which effectively absorbs higher-energy radiation such as UV and visible light. Infrared radiation, which has lower energy, can pass through the dust.

For that reason, the researchers used the James Webb Space Telescope, which is designed to observe the universe in infrared wavelengths. Specifically, they relied on Webb’s Mid-Infrared Instrument (MIRI), a spectrograph capable of analyzing chemical signatures between 5 and 28 micrometers.

ULTRAVIOLET DATA EMBEDDED IN HYDROGEN

Rather than detecting ultraviolet radiation directly, the team searched for indirect evidence of its presence by studying molecular hydrogen, H₂. Although H₂ is the most abundant molecule in the universe, it is difficult to observe because it emits weakly under typical conditions. Strong emission requires high temperatures and densities, such as those found in shock-heated gas around protostars.

Information about ultraviolet radiation is encoded in how molecular hydrogen is excited. By analyzing these signals, the researchers were able to infer the presence and intensity of UV radiation in the protostellar environments.

“Our observations and analyses have confirmed that UV radiation must be produced locally. It can be produced in the shock wave itself, associated with the outflow of material, or directly by the accretion of material onto the central object. It is 10 to 100 times more intense than the average UV radiation in the interstellar medium,” Karska said.

The findings also demonstrate the increased capabilities of the James Webb Space Telescope compared with earlier infrared observatories. Webb can observe hydrogen transitions across a broad mid-infrared range with much higher sensitivity and resolution.

PERCEPTIVE WEBB

“The ability to detect lines and resolve detail is simply unimaginably greater. James Webb showed us so many spectral lines that analysing them will likely take decades,” Karska said. She added that the spectral data provide detailed information about the chemical compounds present in the environments around young stars.

Poland was not a partner in the construction of the James Webb Space Telescope and does not receive guaranteed observation time. Polish researchers must compete in international proposal calls, where applications are evaluated based on scientific merit.

“About one in nine to twelve applications is accepted. It is a great thing for me to be among the group granted observation time, not to mention it was in the first observation cycle,” Karska said.

For Karska, the results also confirm ideas she proposed earlier in her career. “Even during my doctorate, I postulated that UV radiation must be present in these regions, because models without it were inconsistent with the observations of water levels,” she said.

“Now, thanks to James Webb, this has been confirmed and characterized. As a scientist, it is a very pleasant feeling when, after years of hard work, you are proven right. And the James Webb Telescope has opened a completely new window for us: it allows us to study physical processes on scales comparable to the size of the Solar System, processes previously completely invisible to us,” she said.

PAP - Science in Poland, Ludwika Tomala

lt/ zan/

tr. RL