Cancer cells can reprogram their metabolism to survive in different organs, a process that influences their ability to metastasise, according to a study published in Nature by an international team including Sonia Trojan, PhD, from Jagiellonian University.

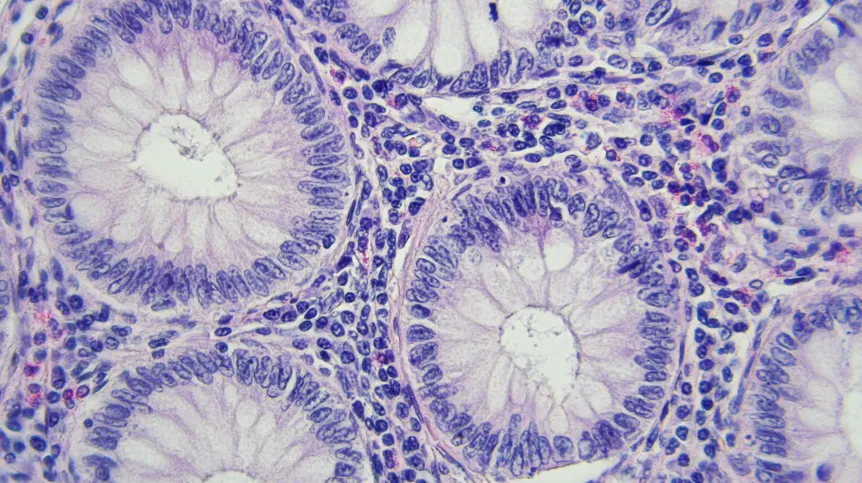

Metastasis occurs when cancer cells detach from a primary tumour and spread through the bloodstream to other organs. Cells that encounter favourable metabolic conditions—such as adequate oxygen, glucose, or amino acids—can survive and form secondary tumours. The brain, lungs, and bones each provide distinct metabolic microenvironments, affecting how cancer cells adapt.

“In our research, we analysed how the metabolic environment of a given organ affects the ability of cancer cells to metastasise. It turns out that cancer cells can very efficiently adapt their metabolism to compensate for deficiencies in their new environment,” Trojan said.

The team measured metabolite levels in specific tissues of mice and genetically modified aggressive breast cancer cells so they could not synthesise certain nutrients, forcing them to rely on the environment.

Using advanced metabolic tracking techniques developed during Trojan’s postdoctoral work with Prof. Matthew Vander Heiden, the researchers traced labelled glucose molecules to determine how cells used nutrients in different organs.

The study found that cancer cells display high metabolic flexibility, often producing missing compounds themselves if they are unavailable in the tissue. An exception was nucleotide synthesis: cells unable to produce nucleotides showed limited tumour growth and metastasis regardless of the microenvironment, pointing to potential therapeutic strategies targeting this pathway.

When asked about predicting metastatic patterns, Trojan said the process remains difficult. “Currently, we rely primarily on statistical observations. We know that certain types of cancer are more likely to metastasise to specific organs. Understanding this process at the molecular level could significantly improve diagnosis and treatment,” she said.

Trojan emphasized that the study is basic research aimed at understanding cancer mechanisms rather than developing a therapy. “Each such discovery represents another step towards more effective and precise treatment,” she concluded.

PAP - Science in Poland, Ludwika Tomala

lt/ agt/

tr. RL