Scientists have gained new insights into the evolutionary history and palaeoecology of European bison and their extinct relatives, showing how only the European bison survived more than 50,000 years of environmental change and human pressure.

The European bison (Bison bonasus) is one of the few species that survived the late Pleistocene extinction of megafauna such as mammoths, woolly rhinos, giant deer, and steppe bison. It is now the largest land mammal in Europe.

However, knowledge of its evolutionary history and coexistence with other Bison species has been limited until now.

The European bison was widespread in Central and Eastern Europe and western Asia in the late Pleistocene (120,000–12,000 years ago) and coexisted with the extinct steppe bison (Bison priscus), which ranged across almost all of Eurasia.

Between 6,000 and 2,000 years ago, bison populations declined in Western Europe, and by the late 19th century, hunting reduced the species to two small populations in the Białowieża Forest (Bison bonasus bonasus) and the Caucasus Mountains (Bison bonasus caucasicus). By the 1920s, the European bison became extinct in the wild, with only 54 individuals surviving in captivity.

The drastic population decline and resulting low genetic diversity limited understanding of the species’ evolutionary history and ecology. For much of the 20th century, European bison were considered forest species because of the environments in which they survived longest.

New research led by scientists from the Mammal Research Institute of the Polish Academy of Sciences in Białowieża and the Australian Centre for Ancient DNA in Adelaide analysed 135 mitochondrial genomes from fossil Bison remains across Eurasia, dating back tens of thousands of years.

The study, published in „Global Change Biology”, shows that the spatial and temporal range of these animals was much larger than previously thought.

The scientists said that phylogenetic analysis identified the steppe bison and two clades of European bison: the extinct Bb1 (bison X) and the modern European bison Bb2. They said the bison clades split into two distinct genetic lines around 97,000 years ago. While genetically distinct, they belonged to the same species.

“All three groups existed in Europe until the end of the Ice Age (Pleistocene), but after the transition to the warmer Holocene (12,000–9,000 years ago), the steppe bison and bison X became extinct, and only the European bison survived,” the study’s authors said. They said the European bison population declined gradually from about 10,000 years ago.

The research also revealed a dramatic loss of genetic diversity at the end of the Pleistocene, evidenced by a decreasing number of mitochondrial DNA haplotypes. Of the eleven haplotypes present in European bison at the start of the Holocene, only four survived into the late Holocene.

The scientists said that stable carbon and nitrogen isotope analyses of bones allowed researchers to reconstruct diets and habitats. “In the late Pleistocene, the steppe bison, bison X, and European bison had similar diets, foraging in open environments with grass or mixed diets. Stable carbon isotopes show that European bison shifted to more forested habitats in the middle Holocene (about 6,000 years ago), when much of central and northern Europe was forested. At that time, human pressure from Neolithic agriculture and hunting increased, pushing the bison deeper into less accessible forests,” said co-author Emilia Hofman-Kamińska, PhD, from the Mammal Research Institute of the Polish Academy of Sciences.

An exception, the scientists said, was a middle-Holocene population near Lake Sevan in Armenia, which occupied open high-mountain meadows at 1,900 meters above sea level.

Fossil DNA also showed that the two modern lineages, the lowland bison and the lowland-Caucasian bison, remained in the same mitochondrial clade (Bb2) throughout the Holocene.

“The slight genetic differences observed today between these groups seem to be the result of extended geographic isolation over time and a different number of ancestors during the species’ recovery after extinction in the wild, and not of separate evolutionary paths. Therefore, there is currently no justification for keeping these groups isolated as separate genetic lines. This approach has significant consequences for the conservation management of modern bison populations, where limited genetic diversity, small numbers and isolation of subpopulations pose a threat to their conservation and survival,” the scientists said.

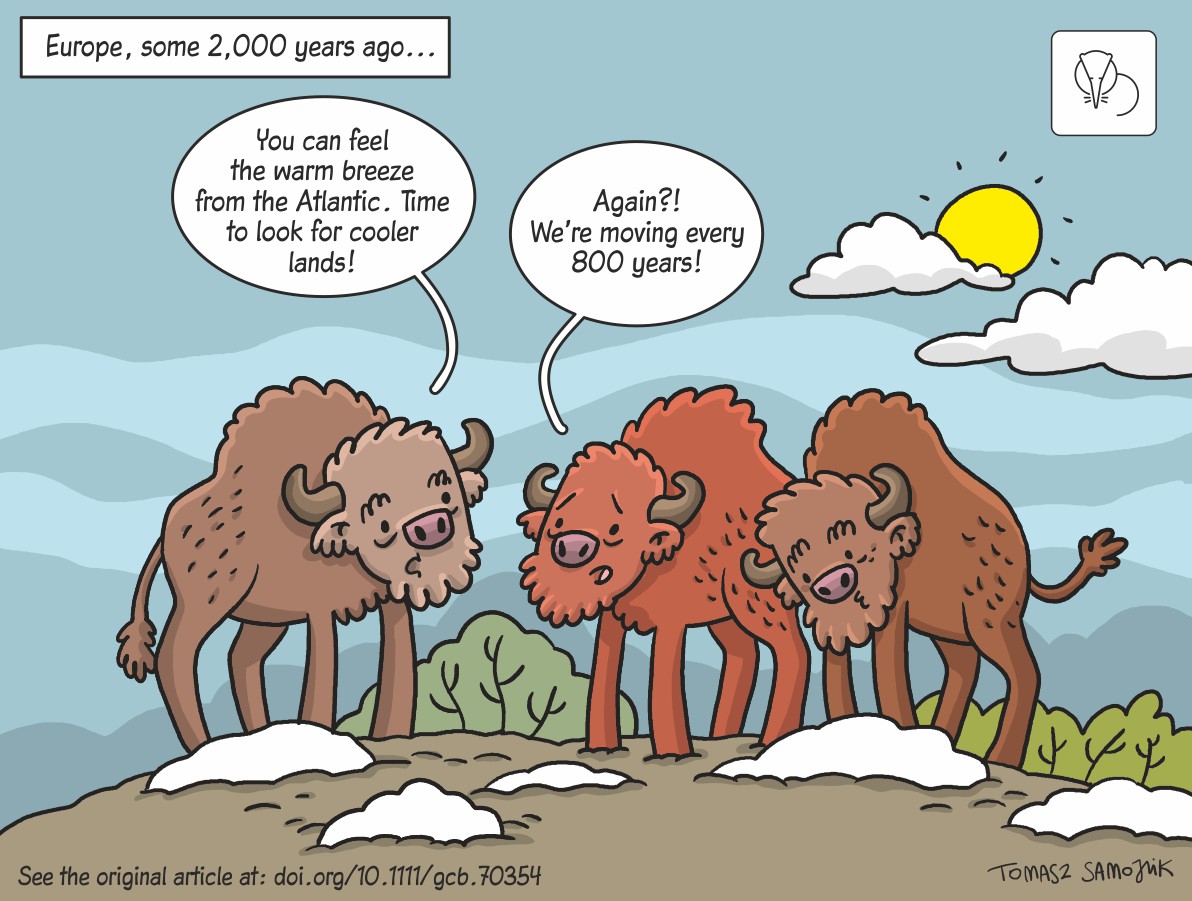

They said the study also examined temporal changes in bison populations over the last 6,000 years. “During this period, the number of discovered remains increased initially every 1,750, and then every 830 years. This coincides with the decline in the occurrence of bog oaks in Ireland. The smaller number of oaks was associated with colder and wetter periods of Atlantic circulation, which were not favourable to these trees, or to people, but favoured bisons, which, as previous research indicates, were adapted to a colder climate. These periods were related to shorter growing seasons, reducing the amount of crops and the human population, and therefore human pressure on the bison. These periods include, for example: cooling at the beginning of the so-called Dark Ages (5th-10th century) and the Little Ice Age (14th-19th century),” said Professor Rafał Kowalczyk from the Mammal Research Institute of the Polish Academy of Sciences.

The scientists said the study, which offers a comprehensive picture of the evolutionary history and palaeoecology of Bison species in Europe during the Late Pleistocene and Holocene, shows that although the species had similar environmental niches, only the European bison survived. Its survival was likely due to its adaptability to climate change, environmental shifts, and human expansion.

They added that without conservation efforts, which began several hundred years ago, the European bison would probably have joined the list of extinct megafauna, alongside the steppe bison, bison X, and aurochs.

PAP - Science in Poland

zan/

tr. RL